As China and Russia modernize their militaries and restructure their forces, the U.S. military is wary that its traditional advantages may be negated in a potential war with either, or both, powers.

In the face of a rising China and resurgent Russia, some pundits point to the U.S. military’s surplus of combat experience and large-scale logistical expertise in massing forces as an overwhelming advantage.

But that may not actually help that much against a peer adversary capable of launching cyber attacks the minute mobilization orders are cut, according to retired Army Gen. Jack Keane, a former vice chief of staff for the U.S. Army.

“A commander today at Fort Bragg, in the pre-deployment phase, will be disrupted by cyber attacks on personnel manifests, loading rail cars [and] moving convoys to ships,” Keane, who serves as chairman of the Institute for the Study of War, said Wednesday at a Foundation for Defense of Democracies forum in Washington, D.C.

The days of permissive strategic deployments — like the 2003 Iraq invasion — are gone, he said.

“A TRANSCOM commander in charge of military sealift will tell you he doesn’t have enough ships or airplanes to get us to the theater," Keane said. "He’s going to be disrupted entirely in route because his cyber networks are unsecure and he’s going to be disrupted kinetically.”

China, for instance, doesn’t have to move troops and equipment across the vast Pacific Ocean. A war in the South China Sea or over the Taiwan Strait would be in its backyard. The Chinese Communist Party has also done well to modernize its forces, partially by copying American designs and strategies, according to U.S. officials.

“I would bet on an American soldier, sailor, airmen, Marine with combat experience any day over a Russian or Chinese counterpart,” said Michèle Flournoy, a former senior Pentagon official under President Barrack Obama. “But this is going to be a different kind of warfare.”

“It’s been a long time since we fought without domain supremacy from the early moments of conflict," she said at the think tank event. "We have never fought with constant cyber harassment, losing comms, connectivity, the ability to plug into the network, constant attacks in space.”

There won’t be time to slowly mass forces before surging into a conflict, either. The trick will be to, very early on, overwhelm an opponent nation, “imposing costs so quickly that they choose an off-ramp and they choose not to escalate further,” Flournoy said.

Both China and Russia are nuclear powers. Finding the off-ramp quickly should be the primary goal of U.S. strategy. But that takes a totally different approach and kind of war-fighting, according to Flournoy.

“While I have complete confidence in our forces’ ability to adapt to that, we’re only now starting to conceptualize, start to train people to it," she added.

But there is good news: China and Russia, while not paper tigers, do have vulnerabilities.

Where China stands

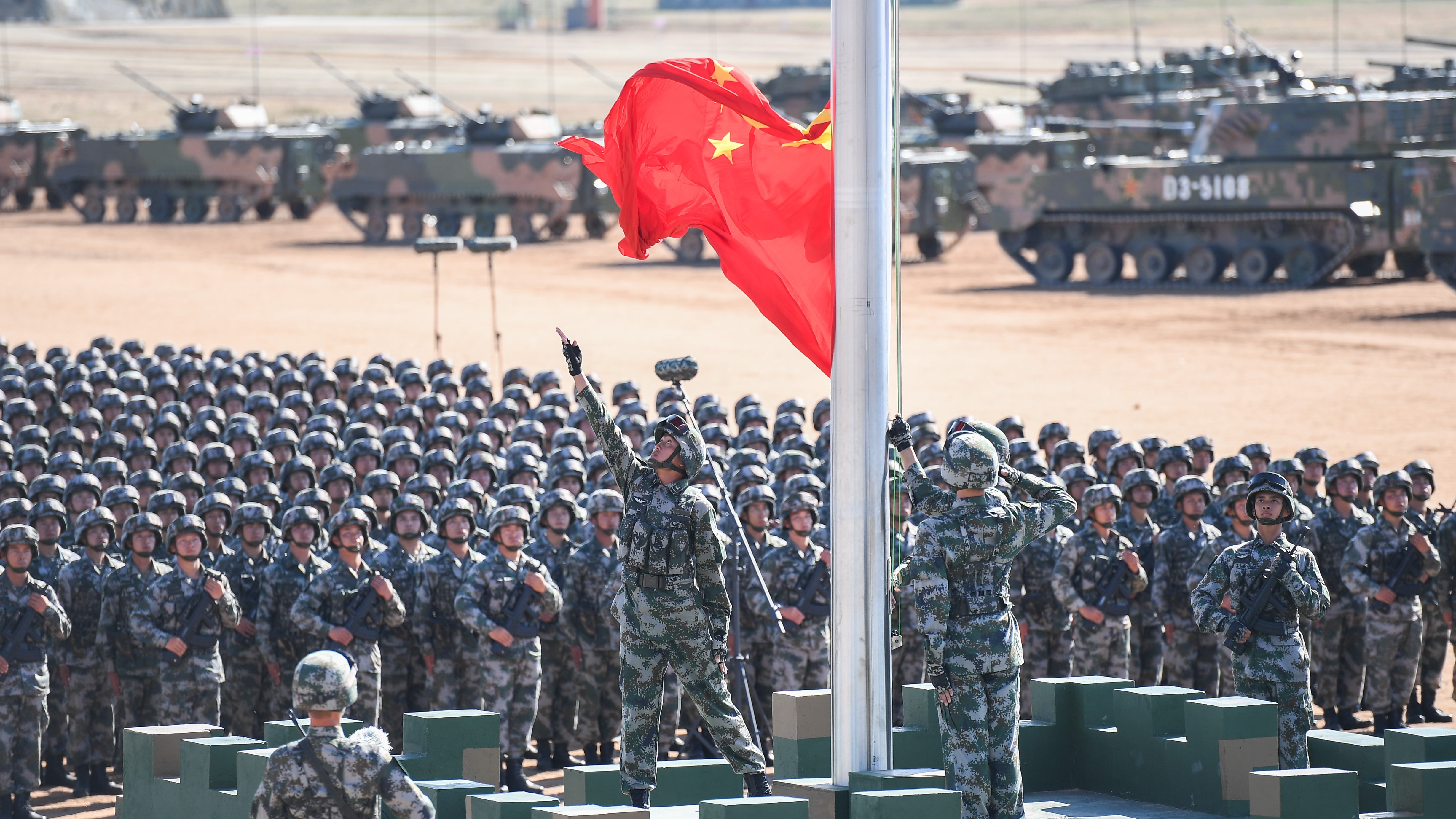

China has gone through something of a military revolution, and the Communist party has purged hundreds of generals from its ranks. Some of those purges are part of a consolidation of power under Chinese Premier Xi Jinping, according to Keane, but the reforms implemented by removing corrupt or ineffective leadership shouldn’t go unnoticed.

“They looked at us very closely,” Keane said. “And they’ve organized similar to us. We keep our administrative functions and our training functions separate from our operations, and they’ve done the same thing.”

For instance, China established five regional commands, similar to the U.S. military’s combatant commands. The People’s Liberation Army, which comprises all China’s armed forces, has also been working to mirror U.S. joint operations by integrating air, land and sea power, “but likely not achieving the kind of competence we have,” Keane said.

“They are not battle tested and they’re aware of that," he added. “I think they would have major command and control problems — that’s just the nature of the communist state in dealing with dynamic, fluid situations on the battlefield.”

The criticism is similar to those hurled at some Middle Eastern militaries: troops from authoritarian countries have centralized command structures that fail to adapt during combat situations in real-time.

The U.S. military, by contrast, works to implement mission command doctrine, which is designed to help troops on the ground adjust their original plan in combat without contacting senior leaders for help. Under this concept, the emphasis is on the outcome of a mission rather than the specific means of achieving it.

So, while U.S. troops are unfamiliar with the multi-domain battlefields of the future, they do have experience managing large-scale combat operations, calling audibles to adapt to new situations, and flexing resources to problem areas across the world.

China doesn’t have that experience, yet. But the country’s military leaders are well-aware. The idea of a “peace disease” has been raised in editorials for the Chinese military’s official newspaper, the South China Morning Post reported last year. The disease originates from the fact that the last time the PLA fought a major battle was during its unsuccessful war against Vietnam in the late 1970s.

Where Russia stands

Russia, meanwhile, does have combat experience.

“As a result of Syria and Ukraine, you have a Russian military that is blooded and has a couple of proving grounds for new technologies and techniques,” said Aaron Wess Mitchell, a former assistant secretary of state focused on European affairs.

“Syria, you have something like an analogue to the Spanish Civil War,” Mitchell said at the think tank forum Wednesday. “You have a crisis on the periphery that has allowed bigger players to shape and test their assumptions about what a future war would look like.”

Utilizing cyber attacks, information warfare and soldiers in sanitized uniforms, Russia has been enormously successful in staying below the level of conventional warfare, according to Keane. This has been commonly called “hybrid warfare."

“There’s no reason why they won’t continue to do that," Keane said. “This is warfare that’s engaged every single day in trying to obtain geopolitical influence.”

But Russia has serious military problems, Keane noted. Moscow has professionalized only 30-40 percent of its armed forces. Those forces are “very capable” and “would give us a challenge in the Baltics and Eastern Europe,” Keane said.

But the rest of the Russian military is still built around conscripts, drafted to serve one year and generally unreliable. It is also commonly noted that the Russian economy has stagnated in recent years, which could hurt military modernization, but the extent to which that is a factor is a subject of debate.

“They focus on large exercises much more than we do,” Rob Lee, a former U.S. Marine Corps officer and doctoral candidate who focuses on Russian defense policy at King’s College London, previously told Military Times. “They do plenty of battalion, regimental, brigade, or division-level exercises, not to mention the annual strategic exercise, which we don’t do very often.”

RELATED

The past decade of war has eroded the decision-making confidence of young leaders, Army general says

“But I think the quality of the individual soldiers and small unit training is far behind ours,” Lee added. “And again, they still have a lot of conscripts, particularly in their ground forces, who only serve for one year, and are hardly the most motivated soldiers.”

By contrast, the U.S. military is all-volunteer, and weapon sales to the Pentagon are booming under President Donald Trump’s administration.

But Keane warned against some of the existing lines of effort.

“The money is there, but we need to put our heads together on what we actually need,” he said. “If we’re just going to improve legacy systems and a whole bunch of programs of record that are tied to that ... we’re wrong.”

Keane said the U.S. military also doesn’t need to necessarily re-create the forward deployed environments of the Cold War in Europe and the Pacific, “but we need more deterrence in both of those theaters than we currently have to reduce the weight of a major strategic deployment and the vulnerability we currently have.”

Kyle Rempfer was an editor and reporter who has covered combat operations, criminal cases, foreign military assistance and training accidents. Before entering journalism, Kyle served in U.S. Air Force Special Tactics and deployed in 2014 to Paktika Province, Afghanistan, and Baghdad, Iraq.