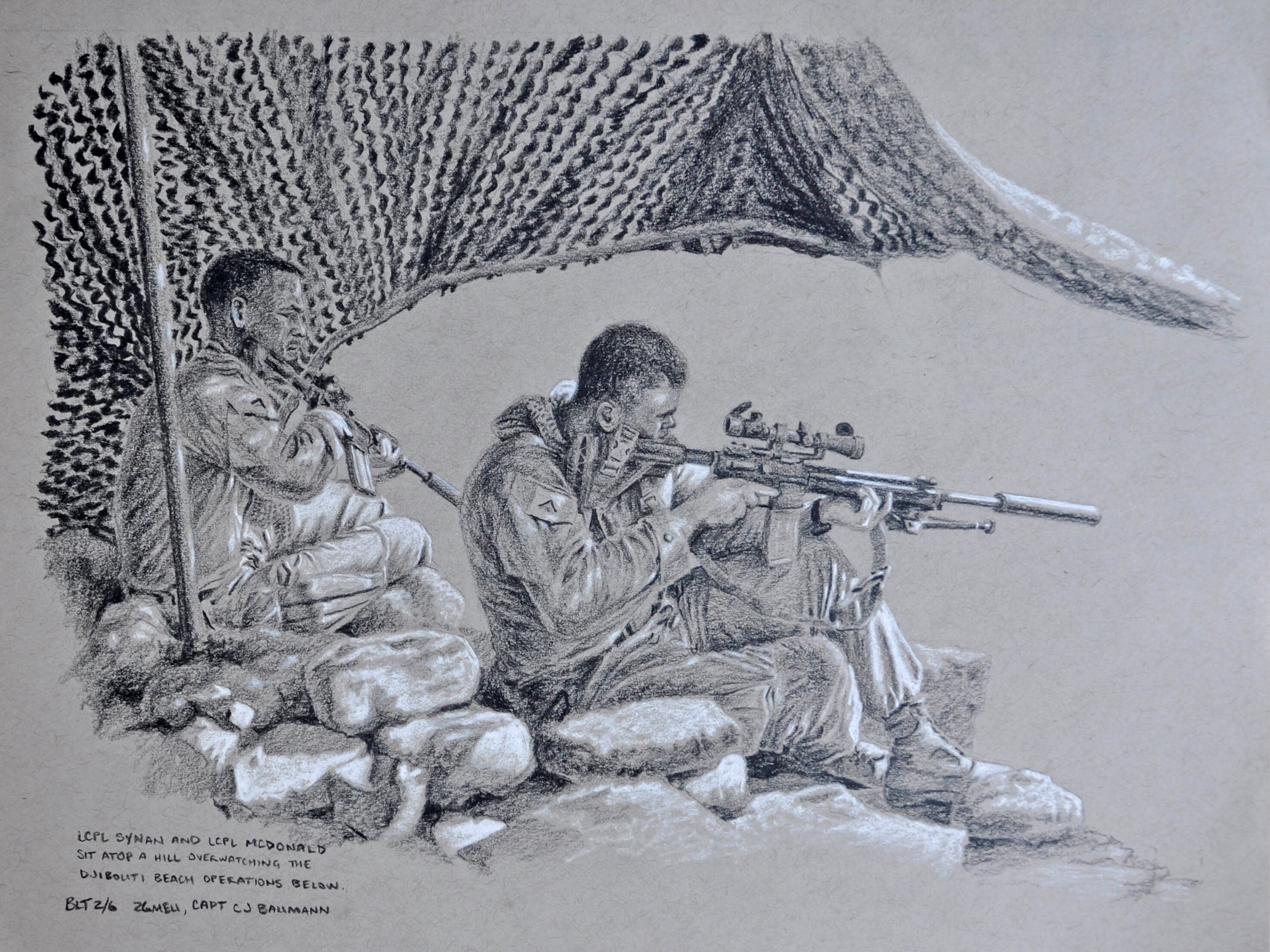

It was a hot day in the African desert with the 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit, on a deployment to Djibouti, Africa.

A Fox Company Marine lieutenant with 2nd Battalion, 6th Marines, stood facing thirty-some Marines as he briefed them before that day’s live-fire exercise.

Marine Capt. C.J. Baumann stood behind them.

But Baumann’s weapon of the day wasn’t a firearm. It was his pencil and sketchbook.

The piece he eventually created from that scene — an approximately 18-by-66-inch, three-piece pencil drawing, which took him about 50 hours to complete — now hangs in Heywood Hall at the Marine Corps base in Quantico, Virginia.

The logistics officer, who recently started as a warfighting instructor at The Basic School, hopes that it will inspire every Marine who walks by.

“It dawned on me that when I captured that, not only were his Marines going to be able to relate to that, but every single lieutenant who walks through the halls” will as well.

These briefs — which may seem tedious for Marines in school — never go away, and “I think I was able to capture and connect in their mind the reality that what we do here actually matters.”

Art can do that, Baumann says.

He is one of only a few active-duty combat artists with the combat artist secondary military occupational specialty and part of the “combat artists program” at and funded by the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Virginia.

Through the program, which dates back to 1942, Marines, reservists and civilians “document Marine Corps life on the battlefront,” and at home and in training.

The MOS is secondary, which means residents can take about two weeks at a time — away from the regular duties of their primary MOS — to embed with units as an artist and capture their experience and ultimately the essence of the Marine Corps.

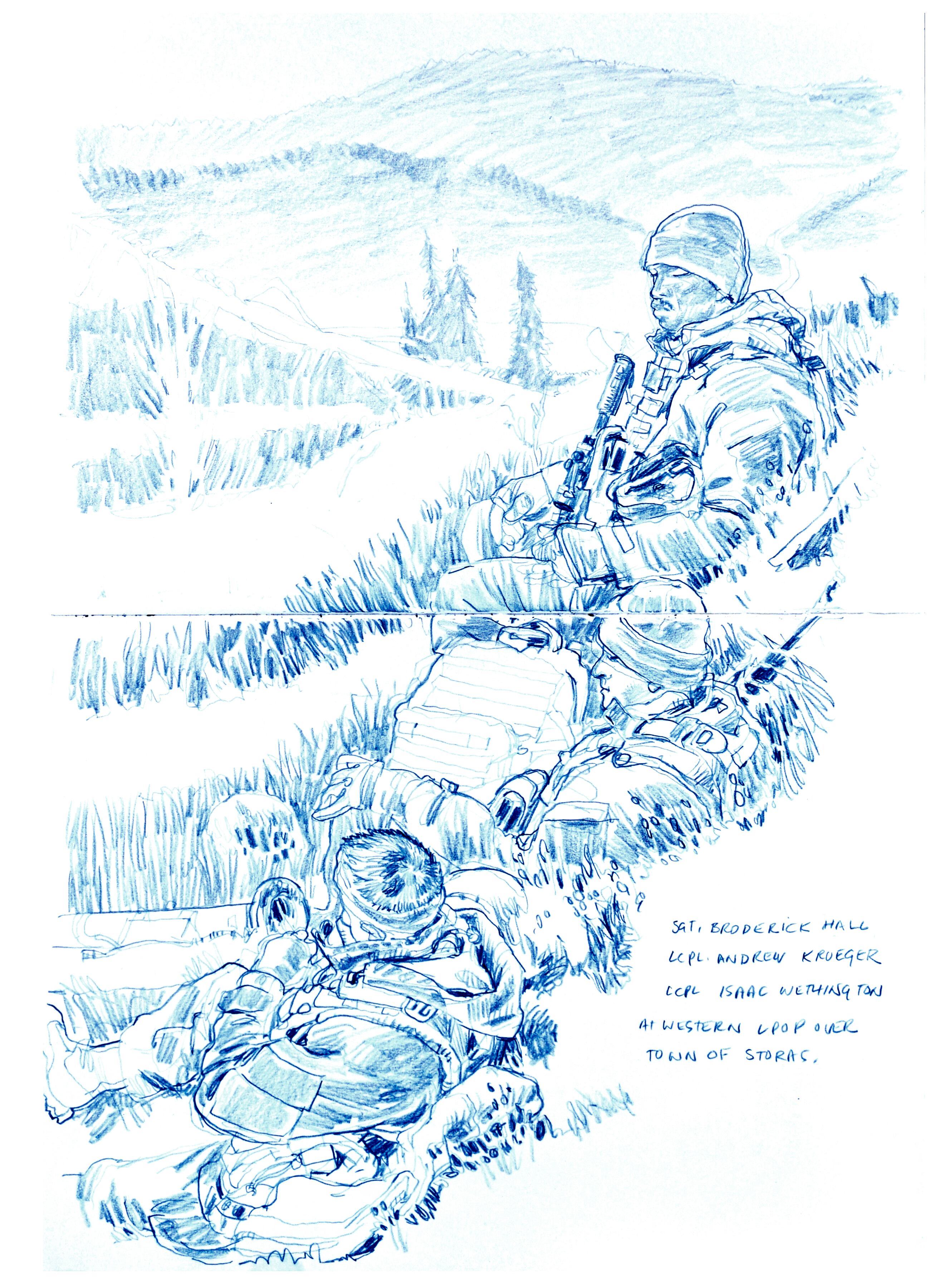

In the past few years, artists with the combat artist program at the museum have gone from Djibouti, Africa, to Twentynine Palms, California, to capture part of the monthlong combined arms ITX exercise there. More recently, they joined the Trident Juncture exercise in Norway.

‘GO TO WAR, DO ART’

“Go to war, do art,” program founder Brig. Gen. Robert Denig, also the Corps’ first director of public information, said in 1942.

It is now the battle cry of the Marine combat artists.

The museum opened a combat artists art studio in 2017 — the same year the combat art gallery opened at the museum. Every second Saturday there is an event open to the public, sometimes with lectures, sometimes live models.

For the 100th anniversary of women in the Marine Corps in 2018, the program hosted a model dressed in old World War II attire for artists to draw.

Historically, every military branch has combat artists of some kind.

But the names of the greats who have been involved with shaping the Marine museum program in some way are hallowed to young Marine artists like Baumann.

Kristopher Battles is a contemporary fine artist and former enlisted marine who re-enlisted to join the combat arts program. Retired Chief Warrant Officer Marine Mike Fay, who first served as an infantryman and later a combat artist, was known for his art from Iraq and Afghanistan.

Col. Craig Streeter, the current commanding officer at the Virginia Military Institute, has served as a Marine combat artist. Freelance illustrator Victor Juhasz has had his work published by large outlets like The New York Times.

Baumann’s deployment partner, Richard Johnson, is currently a civilian field illustrator in the program. His illustrations from the invasion in Iraq and war in Afghanistan are featured in the Smithsonian.

On display in the combat art exhibit until April 2019 is “A World at War,” and a look inside everyday activities of Marines during World War 1.

The exhibit officially opened June 6, 2018 — the 100th anniversary of the Battle of Belleau Wood in France — and with 92 pieces from 42 artists documents everything from the “grisly battlefields” to the “combat debut” of Marine aviation to “Navy battles against German U-boats.”

The museum says that this artwork from the homefront includes “posters intended to energize Americans to donate books, plant gardens, nurse the sick and wounded, and give their overall support to the war effort on a scale not seen before.”

Art had a way then of moving the hearts and of viewers and even move them to action.

And it is still just as impactful today.

“The Marine Corps is proud of its history and has a proud record of what it does,” Baumann said. “But a sketch can incorporate emotion and perspective.”

CAPTURING EMOTION

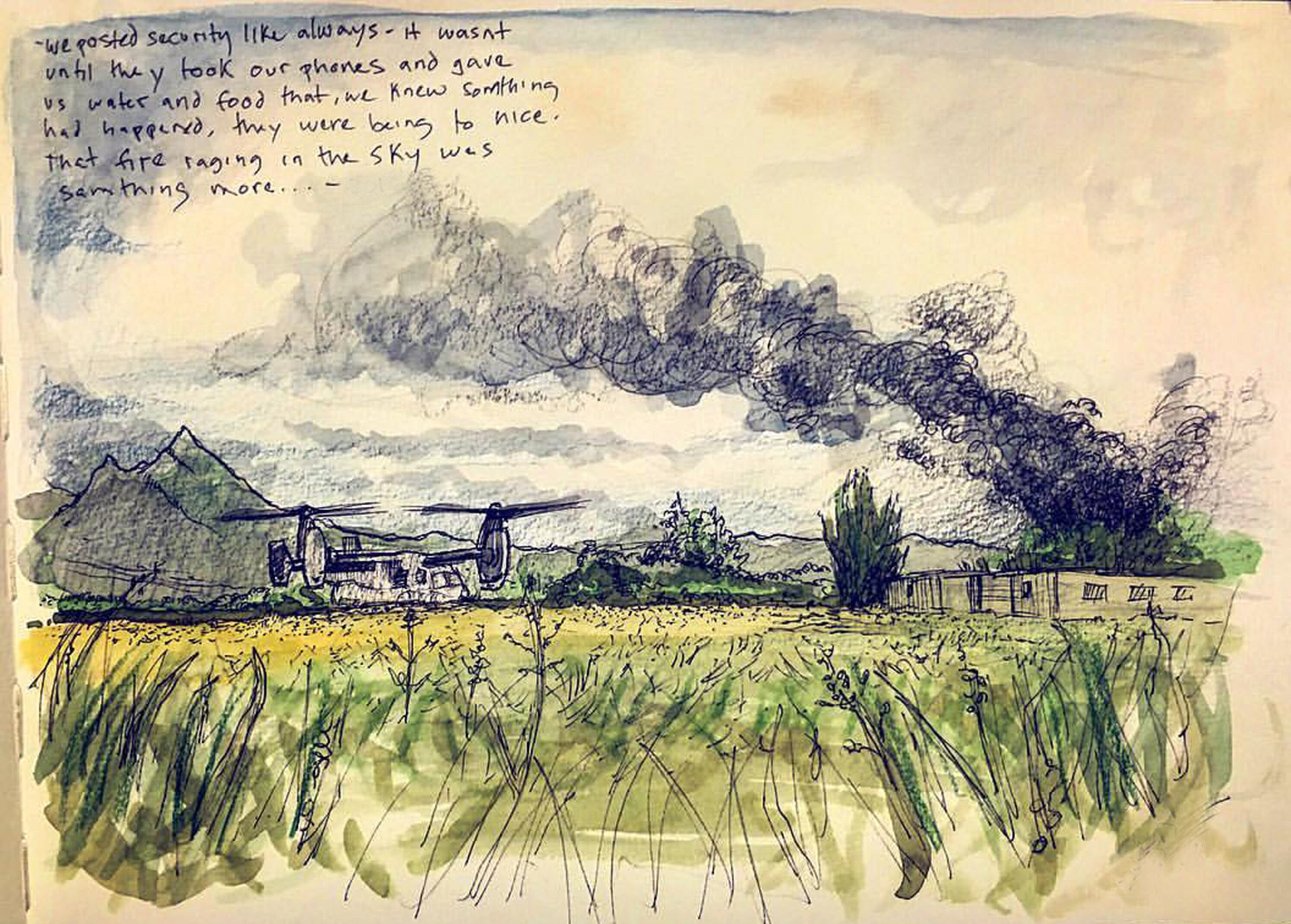

One of the more powerful moments in Sgt. Elize McKelvey’s career was on a deployment in 2015 with the 15th MEU.

On a stop in Oahu, Hawaii, a Corps Osprey went down, and two Marines were killed.

McKelvey was right there — with her sketchbook and camera, which she carries with her.

After the accident, McKelvey was able to give the Marines’ families some of the photos of their last moments.

Since she had been attached to the same unit for six months prior the deployment, she had a whole archive of photos in addition to photos of the incident.

But she also painted the families portraits of their Marines, as well as a rough sketch of the Osprey crash, which she felt were more powerful and well received.

“The camera didn’t capture all the emotions that the drawing and paintings were able to capture,” she said.

It was at age 11 or 12 that McKelvey decided she wanted to be an artist. But it was in a 2010 undergraduate art history course at the Art Institute of Boston, where she was getting a bachelor’s degree in illustration, that McKelvey’s professor for “ten minutes brought up combat art.”

McKelvey was hooked. She had no idea there was art in the military, she said. Though she had a drive to join the military, she had never thought she would be able to do both. So she reached out to some of the combat artists her teacher mentioned ― many of the same that Baumann knew.

They told her, “Make sure you’re joining for the fact you want to be a Marine, not because you want to do art in the Marine Corps.”

And she did. McKelvey decided to go the enlisted route because she thought, “If I was going to share the Marine Corps story, I really wanted to see it from the ground up — from that private level all the way up.”

The skill that it takes to be a member of the combat arts program is very technical, she says.

“You have to be able to traditionally paint, and have understanding of anatomy, and be able to draw from life and movement,” she said.

McKelvey learned a love of art from her artistic mother and grandfather, who was an artist for the Department of Defense during the Korean War. And though McKelvey’s father had been in the Army, she still didn’t feel like she had a strong military background or understanding of the Corps.

“How am I going to share stories of Marines if I don’t know myself what they’ve gone through?”

McKelvey shipped off to boot camp the day after she graduated college. Her military occupational specialty was combat camera, now revamped as communication directorate, and McKelvey works in the print shop and does graphic design for the Marine Corps.

For her, her primary and secondary MOS easily go hand-in-hand.

A Houston visit to NASA resulted in a piece of art depicting the first female Marine astronaut, Lt. Col. Nicole Mann.

In 2018, McKelvey led a team of seven to create a mural at Marine Week Charlotte — which included historical aspects of the Corps in the North Carolina town, like the first black recruit, Pvt. Howard Perry, a Charlotte native.

She also went to Twentynine Palms, California, in 2018 to do field illustrations at the ITX there.

And she recently got to paint the Corps’ 300th Medal of Honor recipient.

Retired Sgt. Maj. John Canley was bestowed the medal in 2018, more than 50 years after his heroic actions as a gunnery sergeant in Hue City, Vietnam.

McKelvey interviewed a former Marine private who served under the gunny, John Ligato, to get “his perspective and what he saw,” and draw her piece from that.

Her acrylic painting — painted in the program’s studio space with their supplies — was of “one of the moments that earned (Canley) the Medal of Honor.”

As a retired Marine captain and the current deputy director of the museum, Charles Grow penned in 2017 in Leatherneck magazine, “the Marine Corps is looking for a few good artists.”

“The artists should have a host of operational experience from which to draw (pun intended),” he wrote, and ideally will be a mix of both officers and enlisted Marines.

Interested Marines can submit a portfolio of about 20 works to the program in order to be considered.

McKelvey is trying to get some artists she knows to that point — to join, what she says, is a very important part of Marine Corps history.

“It was Marines sharing Marines stories,” McKelvey said. “Marines in the foxholes, on the front lines, portraying what they saw.”

Andrea Scott is editor of Marine Corps Times. On Twitter: _andreascott.

Andrea Scott is editor of Marine Corps Times.