While all the military services are experiencing a boom in recruiting dating back to the end of last year, arguably none are doing as well as the U.S. Space Force.

The youngest and smallest of the services, the Space Force has hit its recruiting goal every year since its founding in 2019. On the heels of the service exceeding its recruiting target for fiscal 2025 three months ahead of schedule, a top recruiting official describes plans to fine-tune selection processes and consult with organizations — including Major League Baseball team the Washington Nationals — about how to scout for relevant talent and organizational fit as the Space Force grows and matures.

Lt. Col. Jason Cano, recruiting branch chief for the Space Force, told Military Times this month that he was “about to stamp the table before it even starts” for hitting recruiting numbers for fiscal 2026, due to overwhelming interest and a large delayed-entry pool. Service officials have also said that more than one in five Guardian recruits for the current fiscal year hold a college degree, signaling the high quality of selectees.

Because of the surfeit of talent, and limited positions to fill, the Space Force is now calling its recruiters “talent scouts,” Cano said, and seeking ways to zoom in on what the service needs to fill its relatively small selection of job specialties.

“We’re not struggling for people to come in,” Cano said. “So … how do I develop, now that I’ve got everybody knocking at the door, a new accessions model, a new selective criteria to make sure we have the right talent?”

Including Cano, there are a dozen Space Force “talent scouts” tasked with focusing on what he called “subnets” in the population that have what the service wants. Ideally, these prospective recruits are 17 to 22, have some college and perhaps already have some kind of educational background in what the service does.

When it comes to scouting talent, “We’re looking at the industry partners and everything,” he said. “We’re kind of tailoring it to find out [what we want].”

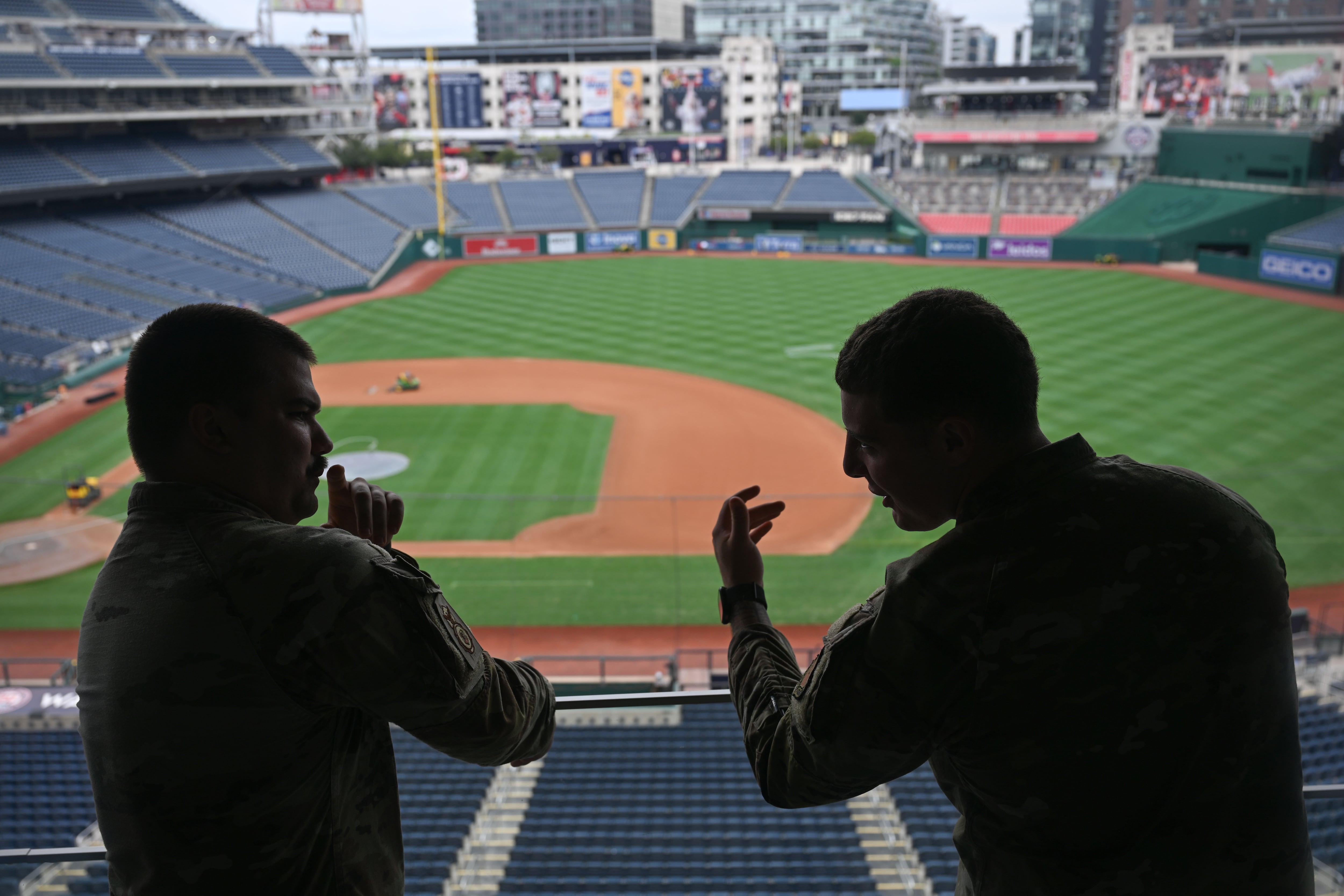

Already in planning is a meeting with the Nationals, Washington, D.C.’s professional baseball team.

Cano said Chief Master Sergeant of the Space Force John Bentivegna connected with representatives from the team at a D.C. event and began a conversation about future collaboration. Bentivegna then passed the contact on to Cano, who followed up. Space Force talent scouts are now in talks to meet with Nationals scouts sometime in November or December, Cano said.

“Now we’re at a point where we’re able to collaborate face to face and see what their workshop is, and how they go and scout talent,” he said.

A Space Force spokesperson confirmed in a statement that the meeting was in planning.

“During this post-season meeting with the Washington Nationals, we aim to learn how the team identifies high-potential athletes before they become clear top-tier prospects, including the early indicators or traits they look for,” the official said. “We also seek to understand the specific tools, platforms, and data sources they use to track and evaluate talent, along with their methods for persuading top recruits to join their organization.”

Gregory McCarthy, senior vice president for Government and Community Engagement at the Washington Nationals, told Military Times in a phone interview that the team was excited about the prospect of advising the Space Force.

A participant in the Air Force/Space Force Civic Leaders Program, McCarthy said he and Bentivegna had a discussion last year about common challenges that turned to recruiting.

RELATED

“Both baseball and the Space Force can be more selective than most organizations can in terms of who they recruit. Both organizations often have a very, very defined, sometimes narrow idea of what they want, and they have to do it on a national basis for a relatively small platform,” McCarthy said.

“And so we said, ‘Gosh, we actually have some similarities here, … What if we have all the Space Force recruiters out to the ballpark and we match them up with some of our scouts from around the country, and we talk about how you attract talent, how you rate talent, how you define what you need.’”

The size of the nexus between scouting for baseball talent and scouting for fit for satellite, intel or acquisition jobs in the Space Force is not entirely clear. While baseball scouts have established stats to work with, such as pitch speed and hit percentage, those don’t necessarily exist for the Space Force.

But McCarthy said the system and structure of data collection on candidates for comparison and analysis was applicable to both organizations.

“They were particularly interested in how do you rate one [candidate] over the other,” he said. He noted that both the Nationals and the Space Force hire for specialized roles — whether pitcher, fielder or signals intelligence analyst.

“They were particularly interested in just how you get all the information that you have,” McCarthy said. “We have, you know, reams of information on every one of our prospects. How do you compile it all up into a profile that you can actually act on? And that’s what I think we’re going to talk about.”

An emailed list of questions sent to the Nationals by Space Force officials, and provided to Military Times for review, provides some insight about where the organizations could find common ground.

“How do you identify high-potential athletes before they become obvious top-tier prospects, and what early indicators or traits do you look for that others might miss?” Space Force officials asked.

Responses in outright form highlighted defining skills and attributes important to overall future potential, assessing risk and defining “intangibles,” such as attitude, character, aggressiveness, work ethic and even family background.

One question from the service about how to persuade top recruits to choose an organization over other competitive offers — particularly relevant as top Space Force candidates may have skills attractive to better-paying civilian employers — got a response focused on vision.

“Clearly show the path to a successful future with them a part of the team/present opportunities for growth & success,” the Nationals’ response read. “Present information or persuasive messaging from alumni who have been part of the past successes/culture building process.”

Getting those responses from the Nationals confirmed to Cano that his headhunter team is on the right track.

“How we look at our lens and how they look at things in their lens is kind of very similar, and that’s why, I think when we sit down, we can talk,” he said.

Fine-tuning the criteria for top candidates, Cano suggested, could also help the Space Force isolate separate targets for different subnets. For older candidates, ages 23 to 27, for example, the service could assess their technical backgrounds and incentivize certifications or skills by offering to bring them in at a higher rank, he said.

The Space Force is also in talks to meet with a “highly selective” military unit to discuss screening criteria for elite teams, said Cano, a special operations veteran.

If these meetings go well, Cano has a dream list of brains he’d love to pick for insights on Space Force talent development. They range from the CEOs of Amazon, Google and Meta to the heads of institutions like Johns Hopkins University and NASA.