Editor’s note: This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service, under the headline “POW Witness: He was forced to watch an execution of U.S. soldiers. 80 years after WWII, his story sparks a search for their remains.” Subscribe to their newsletter.

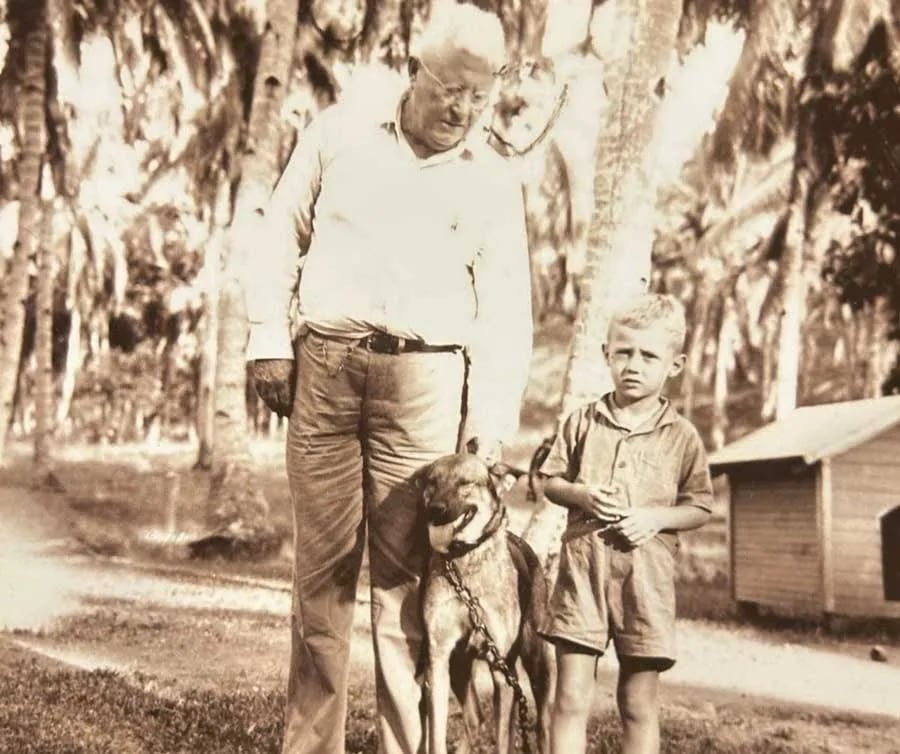

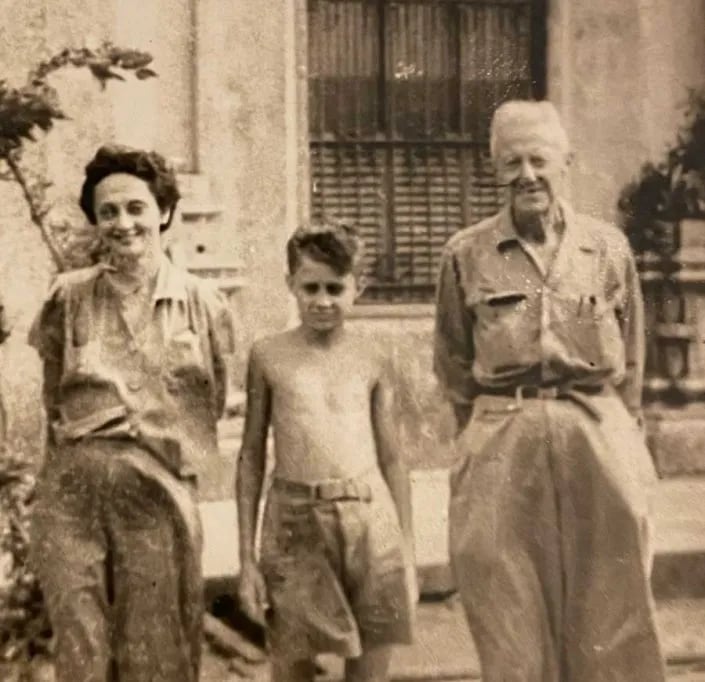

Growing up in the Philippines on the island of Mindanao, Ben Hagans and his friends climbed coconut trees on his family’s plantation, fished for tuna and mahi-mahi, and raced homemade boats in the ocean—all without a stitch of clothing. When Ben was 9, his father took him on a six-month sailing adventure to Australia, India, and Vietnam.

But when he was 12, Ben’s idyllic childhood abruptly ended. Imperial Japan invaded the archipelago nation just hours after bombing Pearl Harbor. And after Allied forces surrendered to the Japanese on Mindanao Island six months later, Ben and his parents spent most of World War II in Japanese prisoner-of-war camps, where his mother was forced into sexual slavery and Ben and his dad nearly died from starvation and illness.

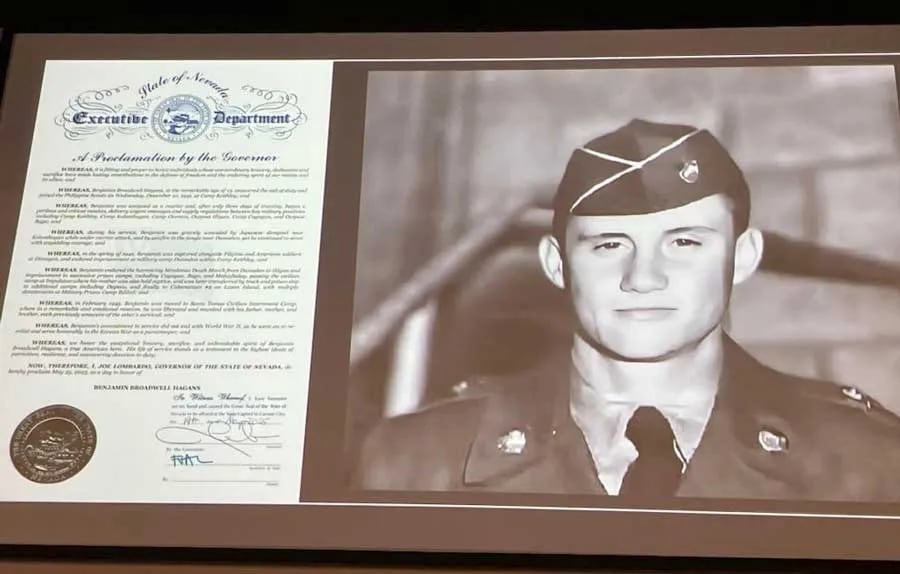

Now, in the twilight of an extraordinary life, Benjamin Broadwell Hagans has emerged as an eyewitness to the savage executions of three U.S. soldiers on July 3, 1942. The 96-year-old retired firefighter’s still-vivid memory of the killings is providing solid clues to finding the remains of not only those soldiers but also those of Army Brig. Gen. Guy Fort, the highest-ranking American military officer executed by enemy forces in World War II.

Fort, who lived on Mindanao Island for four decades, was called “a regular Daniel Boone” because of his wilderness skills and deep immersion in the local culture and languages. He is also remembered for his courage and unwavering resistance to the Japanese after his superiors ordered him to surrender 46 Americans and 300 Filipinos under his command in May 1942. He was executed by his captors that fall because he refused to order bands of fierce Muslim Moro guerrillas to stop fighting after supplying them with rifles and military equipment.

Fort reportedly taunted his executioners to the end, shouting: “You may get me, but you will never get the United States of America.”

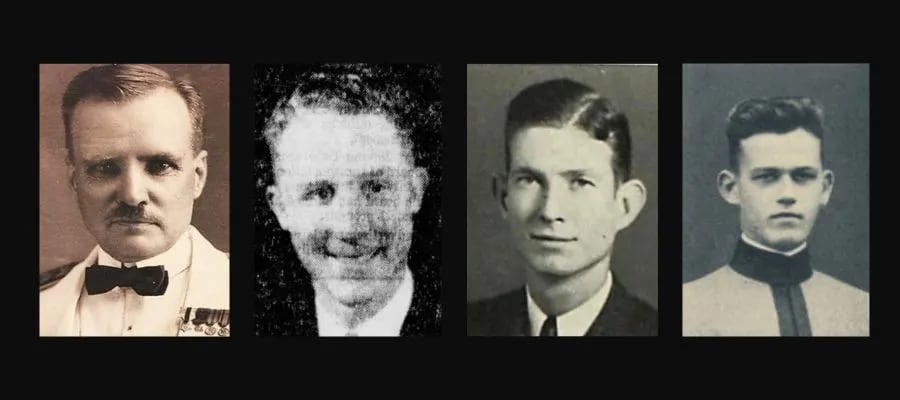

The general and the three U.S. soldiers executed on July 3—Lt. Col. Robert Vesey, Capt. Albert Price, and 1st Sgt. John Chandler—are memorialized on the Tablets of the Missing at the Manila American Cemetery. The tablets are inscribed with the names of 36,286 Americans who perished in the Pacific theater during the Second World War but have no known graves.

In the late 1940s, the U.S. military failed to find the remains of Fort, Vesey, Price, and Chandler and deemed them “nonrecoverable.” But a newly formed POW/MIA group is now hoping Ben Hagans’ sharp memory will lead to identifying the remains at the site of a former Japanese POW camp where the four Americans were executed.

“Never in a million years did I think that someone would still be alive who could help our family—someone who actually knew Brig. Gen. Fort and someone who knows the Philippine islands so well because he actually grew up there,” said Barbara Fox, a Southern California banker and real estate consultant whose stepfather, James Fort, was the son of the general.

The War Horse set out to unravel the remarkable series of events that led to the renewed search for the remains of the four soldiers more than 80 years after the executions—which ultimately resulted in the 1949 hanging of Japanese Lt. Col. Yoshinari Tanaka for war crimes. Interviews with Ben Hagans and family members—along with transcripts and documents from international war-crimes tribunals in postwar Japan, as well as U.S. and Philippine military and POW records—all tell the story.

It was a flurry of emails and phone calls between Barbara Fox and POW/MIA researcher John Bear last September that prompted Bear to take an intense interest in the Fort execution and begin digging into the Philippines’ wartime history.

In May, Bear came across a post by Kelly Hagans, Ben’s daughter-in-law, on a Facebook group aimed at protecting the legacy of the Philippine Scouts, a highly respected supplemental U.S. Army force that was mainly composed of Filipino soldiers and commanded by U.S. officers.

The post highlighted her father-in-law’s life and led Bear to a spellbinding interview Ben gave to the National World War II Museum in New Orleans in 2022 as part of an oral history project. Deep into the interview, Ben mentioned that he had witnessed the execution of American soldiers when he was a POW after serving in the Philippine Scouts.

Bear subsequently found a 1932 aerial photo of Camp Keithley, a former U.S. military installation on Mindanao Island that the Japanese had turned into a POW camp. He then tracked down Marty Hagans, Ben’s son, a retired California State Police officer who lives with his wife and his father in Dayton, Nevada. Bear asked Marty to show the photo to his dad to see if he could pinpoint where Vesey, Price, and Chandler were executed and buried.

As Kelly recorded a video of the conversation between her father-in-law and husband, Ben pointed to specific Camp Keithley features such as the nearby Agus River and a bridge that crosses the river—features that were not easily seen in the photo because of the camera angle.

“I knew then that his memory was sharp as a tack,” Bear recalled. “Once Ben had oriented himself to the photo, he pointed out where he remembered the execution taking place.”

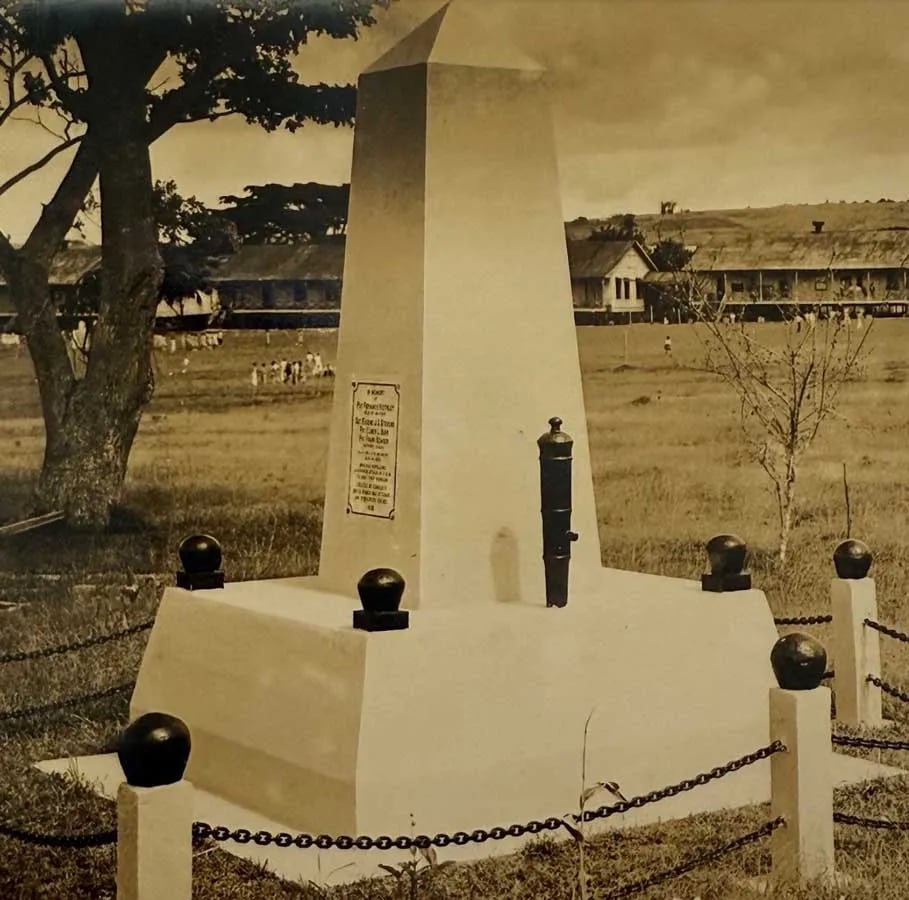

Ben also pointed to the spot where he believes Vesey, Price, and Chandler were buried—close to an obelisk monument that was erected in 1939 to honor Pvt. Fernando Guy Keithley, a hero in the Philippine-American War.

Marty Hagans says when he explained the historical significance of his father’s vivid memories to him, he immediately agreed to help in the decades-old search for the soldiers’ remains. “He was absolutely stunned when he found out that the remains of these heroes haven’t been returned to their families,” his son told The War Horse.

Through his research, Bear is convinced that when teams of American soldiers searched in vain for Gen. Fort’s remains in the late 1940s, they were looking on the wrong side of the Agus River because the north-south axis of the hand-drawn map the soldiers were using was substantially off.

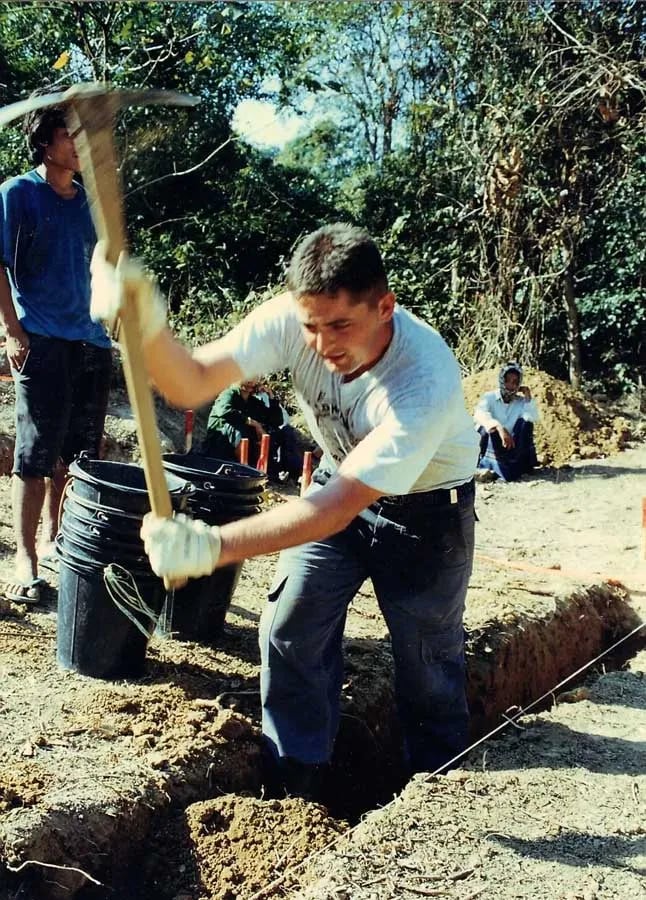

Mike Henshaw, a 25-year U.S. Army veteran from Virginia who has taken part in scores of recovery missions that have led to the identification of the remains of more than 100 service members missing from past wars, reviewed the new evidence and believes there’s a strong chance of locating the four sets of remains.

The timing was auspicious. In January, Henshaw founded the Asymmetric MIA Accounting Group, an all-volunteer nonprofit dedicated to bringing home the remains of missing service members. He and his recovery team plan to travel to the Philippines sometime this fall.

The obelisk monument is now gone, but finding its buried foundation with ground-penetrating radar “should be straightforward—and could provide the key to solving the mystery,” Henshaw said.

Jay Silverstein, a prominent POW/MIA forensic anthropologist, told The War Horse that Henshaw’s team should be able to find identifiable remains if the new information from Ben Hagans and Bear helps them locate the graves.

“There’s a very good chance that you’ll find teeth, and there’s a fair chance you’ll find bones as well. Some of the denser areas of the skull preserve well and are also good for extracting DNA. But it really depends on the environmental conditions. From my experience, skeletal remains—although in some cases degraded by insects and roots, or fragile due to moisture and soil chemistry—endure for hundreds or even thousands of years in most environments.”

The task of locating and retrieving the four soldiers’ remains became more daunting in May 2017 when Philippine security forces conducted an operation to capture an ISIS-aligned emir believed to be hiding in the Islamic City of Marawi, formerly known as Dansalan. The operation was met with violent resistance by Islamist militants, sparking a five-month-long battle.

Because the U.S. State Department still considers the area unsafe to visit, the U.S. Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency has expressed concern about operating there. But Henshaw, a Desert Storm and Operation Iraqi Freedom combat veteran with two Bronze Stars, said his organization was formed to operate in difficult environments where official agencies cannot. “I plan to move forward cautiously but remain determined to honor the fallen,” Henshaw said.

The executions of Vesey, Price, and Chandler occurred several weeks after Ben Hagans’ regiment of the Philippine Scouts surrendered in May 1942, when the prisoners were moved to Camp Keithley. Ben’s mother and father, a U.S. Army officer, also were taken captive.

The Japanese warned the new prisoners not to try to escape. If they did, the captors vowed, they would execute an equal number of POWs.

After four American soldiers escaped on the night of July 1 or July 2, the Japanese showed their captives it was no idle threat. The next day, the captors tied Gen. Fort and three other American soldiers to wooden stakes and prepared to execute them.

Then, Ben said, Lt. Col. Vesey stepped forward and told the executioners: “Cut the general down. I’ll take his place.”

At the last minute, the camp’s commander also granted a reprieve to one of the four Americans originally targeted for execution, Col. Eugene Mitchell, at the request of a Japanese lieutenant who had befriended Mitchell.

Fort’s reprieve proved to be temporary. On or about Nov. 11, 1942, the Japanese executed him by firing squad at Camp Keithley for continually spurning their pleas to tell the Moro guerrillas to lay down their arms. He was buried less than a mile from the graves of the other executed soldiers, researcher Bear has calculated.

For the 12-year-old Ben, Vesey’s execution was excruciatingly painful. Vesey was a 1918 West Point graduate whose hometown was Hope, Arkansas, and he was a longtime friend of Ben’s father, Broadwell Hagans. A major in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Hagans worked closely with Gen. Douglas MacArthur (who called Hagans’ precocious son “Benny”) on the Malinta tunnel complex on Corregidor Island.

“Col. Vesey was a great man,’’ Ben told The War Horse. “He was loved by everybody. I probably saw him three times a week when I was growing up. He would come by our house to talk to my father, but he always greeted me and always told me, ‘It was a pleasure talking to you.’’’

Ben recounted how he and about 100 other prisoners were forced to stand about 50 yards from the execution site as Vesey and the other soldiers were repeatedly bayoneted. “It took them two and a half hours to bleed to death as we stood there,” Ben said. “I put my eyes down and tried not to look.”

The next day was the Fourth of July, and Ben and his parents were among the hundreds of Filipino and American soldiers and civilians forced to march about 25 miles in one day from Camp Keithley to Iligan, where Ben grew up.

The Mindanao Death March, which the Japanese had mockingly dubbed “The Independence Day March,” has been overshadowed in history books by the infamous Bataan Death March on the island of Luzon. But it was no less brutal.

As the scorching tropical sun bore down on them, Ben said, the Mindanao marchers hiked through a mountainous jungle and were given little food and water. Those who were unable to keep up were often shot to death, usually in the forehead.

The Americans were tied together with telephone wire in groups of four. The Filipino prisoners, many dressed only in rags, were forced to walk barefoot on a hot and rocky dirt road.

Ben recalls Filipino villagers along the way slipping the marchers gourds of rainwater, bananas, and rice. Those villagers caught helping the prisoners were beaten or fatally shot, and their homes were torched as a warning to others to stay away.

After arriving in Iligan, the prisoners spent two nights in a dilapidated school building and then were crammed onto a cannon boat that sailed to Cagayan de Oro, where they spent two days on a pier waiting to be taken to a network of POW camps. Ben told The War Horse he watched in horror as Japanese troops raped his mother.

Ben and his father were sent to different camps for military POWs. His mother, Ignacia, who was born in the Philippines and was of Spanish and Scottish descent, was sent to the sprawling Santo Tomas Internment Camp for civilians in Manila and forced to become a “comfort woman”—the Japanese euphemism for a sex slave.

She was one of as many as 200,000 women and girls forced into sexual servitude during Japan’s conquest of Asian countries. The overwhelming majority of the women were Asian—mostly Korean, Chinese, and Filipina. But a tiny percentage were European and American civilians captured during the war.

“She never got over it,” Ben said. “She was very, very bitter and became reclusive and stayed in the Philippines her whole life. I did not resent her for that.”

Ben was only 12 when he joined the 43rd Infantry Regiment of the Philippine Scouts just two days after Pearl Harbor. He had tried to join the U.S. Army, but was turned down because of his age.

The Scouts were thrilled to have him because he not only spoke fluent English but had also mastered Cebuano, the main language spoken on Mindanao Island. So after three days of military training, he was put to work as a courier. He was also issued a .30-40 Krag-Jørgensen rifle and was once gravely wounded when the shrapnel from a mortar round ripped into his legs and left arm.

In his two and a half years as a POW, he was shuttled from camp to camp—seven in total.

“The food was almost nonexistent,” Ben said.

His diet consisted mostly of watered-down rice and only an occasional vegetable. The POWs, he said, were often forced to kill their own food, eating virtually anything that moved for protein—snakes, dogs, cats, rats, and millipedes.

On Oct. 20, 1944, Gen. MacArthur’s forces landed on Leyte Island, marking the start of the Philippines liberation campaign. But little information filtered into the POW camps.

Ben’s eyes light up when he talks about the January day in 1945 when he was transferred to the Santo Tomas camp and saw his parents for the first time in two and a half years.

“Until then I didn’t know where they were, or if they had survived or not,’’ he said.

He also cracks a smile when he talks about Feb. 3, 1945.

“It was about 9 p.m. when I looked at the front gate of the camp, and I saw this tank coming in and thought it was a Japanese tank,” he said. But soon a soldier from the U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division popped out of the top of the tank and asked Ben and his fellow POWs where they could find their Japanese captors. “Then the soldier reached down and started throwing candy bars at us,” Ben said.

After a ferocious firefight in which the Japanese held more than 200 internees hostage in a building, the enemy troops were granted safe passage in exchange for releasing the hostages.

Then, at midnight, the 1st Cavalry laid out a great spread for all the prisoners. “Apples, pears, oranges, sweet rolls, oatmeal, ham, good old Spam,” Ben recalled.

Ben’s teeth were so loose that all he could eat was the oatmeal. But he went through the line nine times.

The next morning, Army medical officers gave all the prisoners a series of shots and vitamin pills and put everyone on a scale. Ben, then 15 years old, weighed 56 pounds.

A few days after the camp was liberated, Ben thought he spotted someone he knew from a distance, but suspected it might be a mirage. Could that be his older brother Bill? In a U.S. Navy officer’s uniform?

“It’s Bill! It’s Bill!” he shouted to his parents, who refused to believe it until they all fell into each other’s arms.

Bill was one of Ben’s four half-siblings from his father’s first marriage. The four had all left the Philippines before the Japanese invaded in 1941. But Bill enlisted in the Navy in Michigan and was sent on a three-year mission in the Philippines to find out the location of the POW camps and who was in them. The short, fair-complected Bill had posed as a Filipino peasant by taking the bark of betel nut trees, mashing it into pulp, and rubbing it over his skin to darken it.

Two months after Mindanao’s camps were liberated, Ben boarded a ship to the States to be treated for a host of diseases, including dysentery, beriberi, parasitic flatworms, dengue fever, and malaria. He was in three military hospitals for a year and a half before a physician discovered Ben had cholera and that all his other diseases were masking the symptoms.

Once he was treated for cholera, Ben recovered and was released within weeks.

Ben, who had been homeschooled in the Philippines, settled in California’s San Joaquin Valley and entered Fresno State to study agriculture and forestry. He had just finished his freshman year when North Korean troops crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea, and President Harry Truman ordered the U.S. military to intervene.

An Army reservist, Ben was called up in his sophomore year. Although Army officials told him he wouldn’t have to go to Korea because he was a former POW, he didn’t ask for an exemption and was sent to Fort Benning in Georgia to train to become a paratrooper. He ended up doing two tours in Korea and getting promoted on the battlefield to second lieutenant.

After that war was over, he joined California’s Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and became a firefighter. He ended his 32-year career as a battalion chief in Tulare County.

He earned a fistful of medals from his wartime experience, including three Purple Hearts and a POW medal. But the one that would mean the most to him—a medal for his service in the Philippine Scouts—has eluded him for decades. He and his son were told the records were among the millions destroyed in the 1973 fire at the National Personnel Records Center in St. Louis.

Ben still has nightmares about the time his Japanese captors beat him severely for stealing oats and rice meant for the horses, the three days he was forced to drink his own urine to survive a “hell ship” transporting POWs, and seeing fellow prisoners having their heads lopped off with swords.

“He has these dreams every single day and every single night,” his son said. “I hear him, and I know which are the bad ones.”

Ben uses a walker now. But that didn’t stop him from celebrating his 96th birthday in July by skydiving. It was his second birthday jump in two years. Counting his jumps as a paratrooper in Korea, that makes 117.

Is he going to stop now?

“Nope,” he said with a chuckle. “The next jump is when I turn 100. That will be the last one.”

This War Horse story was edited by Mike Frankel, fact-checked by Jess Rohan, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Hrisanthi Pickett wrote the headlines.

Ken McLaughlin is a freelance writer based in Scotts Valley, California. He spent 35 years at the San Jose Mercury News as a reporter, editorial writer and editor. He’s written extensively about politics, marine science, Vietnam, immigration, and race and demographics. He has a master’s in journalism from Stanford University and taught aspiring science writers for a decade at UC Santa Cruz.