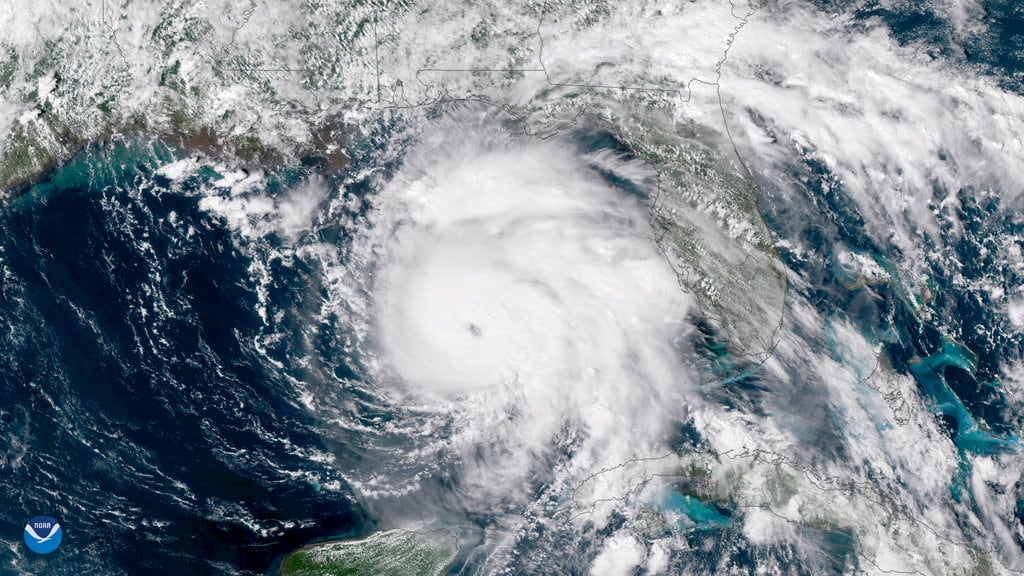

When storms like Hurricane Michael make landfall, the first things they hit often are barrier islands — thin ribbons of sand that line the U.S. Atlantic and Gulf coasts. It’s hard to imagine how these narrow strips can withstand such forces, but in fact, many of them have buffered our shores for centuries.

Barrier islands protect about 10 percent of coastlines worldwide. When hurricanes and storms make landfall, these strands absorb much of their force, reducing wave energy and protecting inland areas.

They also provide a sheltered environment that enables estuaries and marshes to form behind them. These zones serve many valuable ecological functions, such as reducing coastal erosion, purifying water and providing habitat for fish and birds.

Many barrier islands have been developed into popular tourist destinations, including North Carolina’s Outer Banks and South Carolina’s Hilton Head and Kiawah. Islands that have been preserved in their natural state can move with storms, shifting their shapes over time. But many human activities interfere with these natural movements, making the islands more vulnerable.

Barrier islands are made of sandy, erodible soil and subject to high-energy wave action. They are dynamic systems that constantly form and reform. But this doesn’t necessarily mean the islands are disappearing. Rather, they migrate naturally, building up sand in some areas and eroding in other areas.

New islands can form out in the ocean, either because local sea level drops or tectonics or sediment deposition raises the ocean floor. Or they may shift laterally along the shore as currents carry sediments from one end of the island toward the other. On the East Coast, barrier islands usually move from north to south because longshore currents transport sand in the same direction.

And over time many barrier islands move landward, toward the shore. This typically happens because local sea levels rise, so waves wash over the islands during storms, moving sand from the ocean side to the inland side.

Building on shifting sands

Building hard infrastructure such as homes, roads and hotels on barrier islands interrupts their lateral migration. Needless to say, beach communities want their dunes to stay in place, so the response often is to build control structures, such as seawalls and jetties.

This protects buildings and roads, but it also disrupts natural sand transportation. Blocking erosion up-current means that no sediments are transported down-current, leaving those areas starved of sediment and vulnerable to erosion.

Many sandy tourist beach towns along the East Coast also turn to beach nourishment – pumping tons of sand from offshore – to replace sand lost through erosion. This does not interrupt natural sand transportation, but it is a very expensive and temporary fix.

For example, since the 1940s Florida has spent over US$1.3 billion on beach nourishment projects, and North Carolina has spent more than $700 million. This added sand will eventually wash away, quite possibly during Hurricane Florence or the next hurricane to hit the coast, and have to be replaced.

What kind of protection?

In some cases, however, leaving barrier islands to do their own natural thing can cause problems for people. Some cities and towns, such as Miami and Biloxi, are located behind barrier islands and rely on them as a first line of defense against storms.

And many communities depend on natural resources provided by the estuaries and wetlands behind barrier islands. For example, Pamlico Sound – the protected waters behind North Carolina’s Outer Banks – is a rich habitat for blue crabs and popular sport fish such as red drum.

Unmanaged, some of these islands may not move the way we want them to. For example, a storm breach on a barrier island that protects a city would make that city more vulnerable.

Here in Mississippi, a string of uninhabited barrier islands off our coast separates Mississippi Sound from the Gulf of Mexico. Behind the islands is a productive estuary, important wetlands and cities such as Biloxi and Gulfport. Because the Mississippi River has been dredged and enclosed between levees to keep it from spilling over its banks, this area does not receive the sediment loads that the river once deposited in this part of the Gulf. As a result, the islands are eroding and disappearing.

To slow this process, state and federal agencies are artificially nourishing the islands to keep them in place and preserve the cities, livelihoods and ecological habitats behind them. This project will fill a major breach cut in one island by Hurricane Camille in 1969, making the island a more effective storm buffer for the state’s coast.

Geologically, barrier islands are not designed to stay in one place. But development on them is intended to last, although critics argue that climate change and sea level rise will inevitably force a retreat from the shore.

Reconciling humans’ love of the ocean with the hard realities of earth science is not easy. People will always be drawn to the coast, and prohibiting development is politically impractical. However, there are some ways to help conserve barrier islands while maintaining areas for tourism activities.

RELATED

First, federal, state and local laws can reduce incentives to build on barrier islands by putting the burden of rebuilding after storms on owners, not on the government. Many critics argue that the National Flood Insurance Program has encouraged homeowners to rebuild on barrier islands and other coastal locations, even after suffering repeated losses in many storms.

Second, construction on barrier islands should leave dunes and vegetation undisturbed. This helps to keep their sand transportation systems intact. When roads and homes directly adjacent to beaches are damaged by storms, owners should be required to move back from the shoreline in order to provide a natural buffer between any new construction and the coastline.

Third, designating more conservation areas on barrier islands will maintain some of the natural sediment transportation and barrier island migration processes. And these conservation areas are popular nature-based tourism attractions. Protected barrier islands such as Assateague, Padre and the Cape Cod National Seashore are popular destinations in the U.S. national park system.

Finally, development on barrier islands should be done with change in mind and a preference for temporary or movable infrastructure. The islands themselves are surprisingly adaptable, but whatever is built in these dynamic settings is likely sooner or later to be washed away.

Anna Linhoss is an assistant professor in Agricultural and Biological Engineering at Mississippi State University. Her research interests include hydrology, ecology, modeling, watershed management, and climate change. Her work crosses disciplinary boundaries through collaboration with a variety of departments including Law, Anthropology, Wildlife, and Forestry. She works both locally and internationally with projects and collaborators throughout the southeast and in southern Africa.