Attorneys for the former commanding officer of the destroyer Fitzgerald want a military judge to toss the court-martial case against Cmdr. Bryce Benson because public comments from the Navy’s brass scuttled any chance for a fair trial.

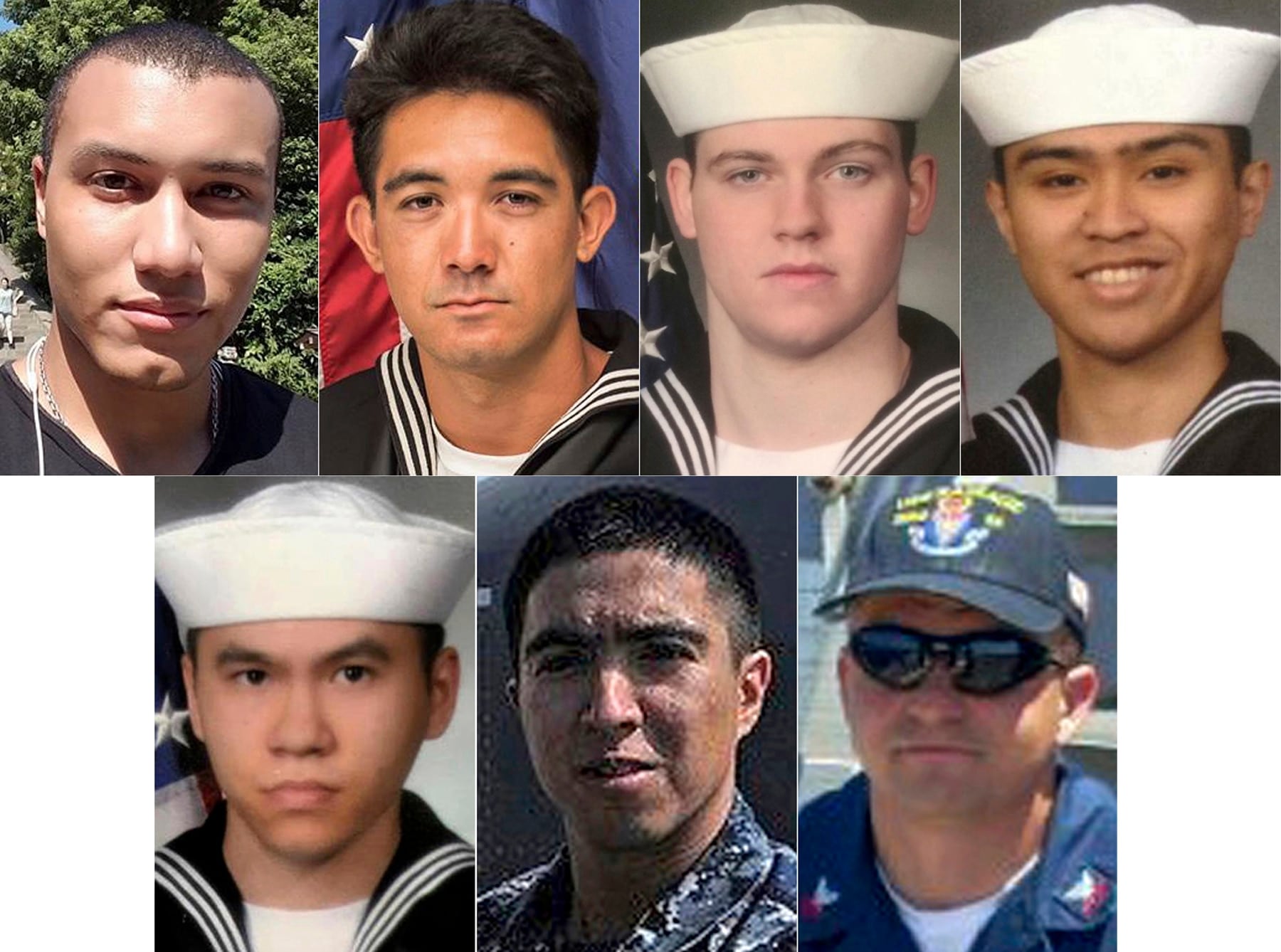

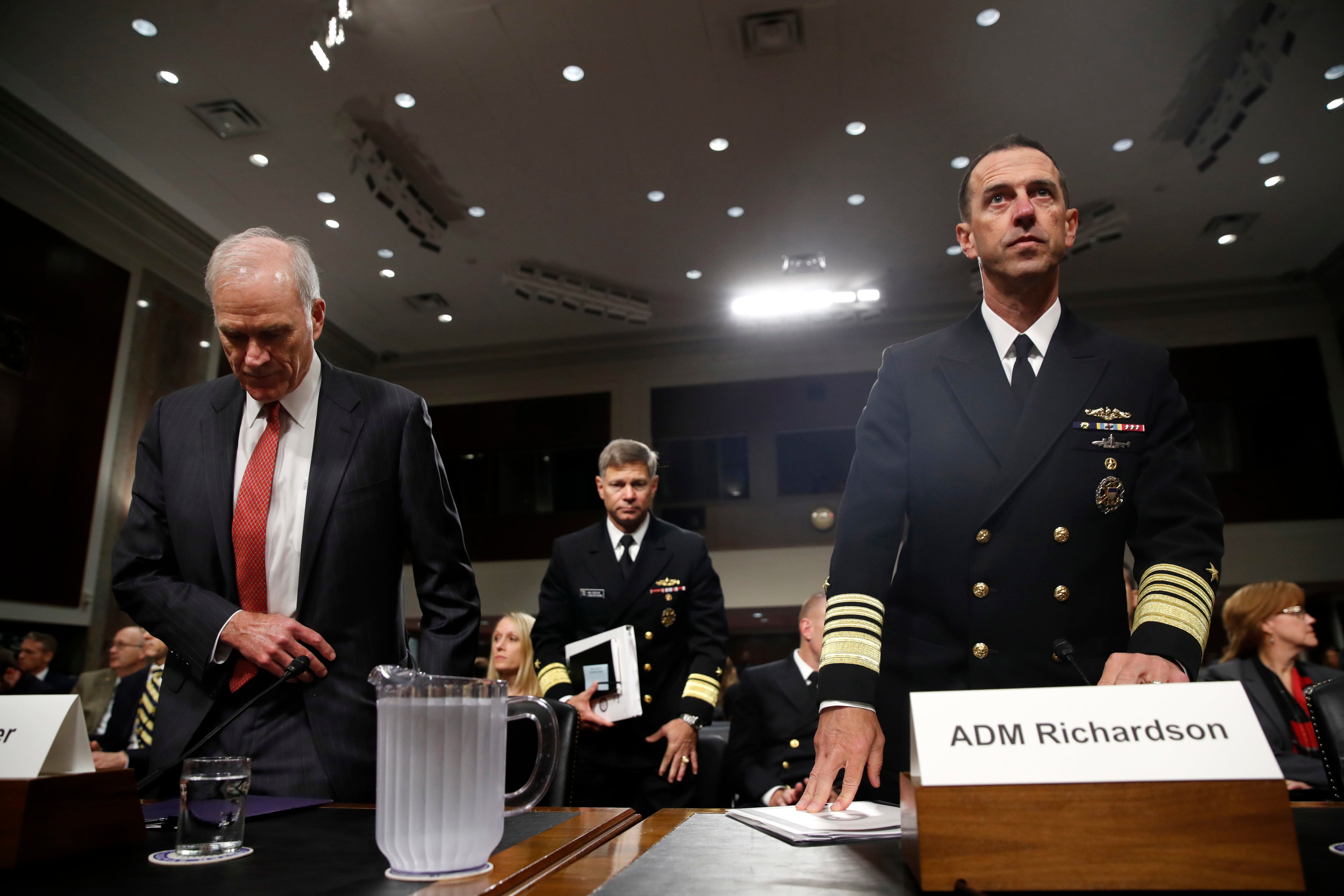

In a 28-page filing punctuated by broadsides against the Navy’s top leaders, Benson’s defense attorneys take aim at both Chief of Naval Operations Adm. John Richardson and Vice Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Bill Moran for statements that blamed Benson for the June 17, 2017, disaster that killed seven sailors.

“CNO and (VCNO), in coordination with other senior Navy leaders, have so frequently blamed Commander Benson for his ship’s collision that no panel could fairly sit at his court-martial,” attorney Lt. Cmdr. Justin Henderson wrote in a motion filed Wednesday.

When the hulking Philippine-flagged container ship MV ACX Crystal speared into the Fitzgerald off the coast of Japan, it smashed through Benson’s sleeping quarters. Shipmates found him hanging from the destroyer’s side.

Now assigned to the Navy Yard in Washington, D.C., Benson is being treated at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for traumatic brain injury and post-traumatic stress disorder, according to Henderson.

In the aftermath of the Fitz’s collision, Navy leaders should have kept “clean hands” regarding their public utterances to ensure Benson received a fair trial, one where a jury of officers wouldn’t be influenced by knowing what their bosses thought about the defendant, the filing states.

“CNO’s hands were anything but sanitary," and he joined with other Navy leaders to commit unlawful command influence against the ailing skipper, Henderson argued in his motion.

Dubbed by Navy attorneys the “mortal enemy of military justice,” unlawful command influence — or UCI — occurs when superiors utter words or take actions that coerce the outcome of courts-martial, imperil the appeals process or undermine the public’s confidence in the military by appearing to tip the scales of justice.

Navy officials declined to address Henderson’s contentions specifically this week.

“The Navy does not comment on pending litigation," Navy spokesman Capt. Gregory Hicks said in an email. "Our fair and transparent military justice system allows all accused to advocate in their defense.”

Another spokesman, Lt. Cmdr. Daniel Day, pushed back on similar assertions by Henderson in May.

“Those accused are always presumed innocent until proven guilty, and our communication of the status of criminal proceedings have been fact-based and in accordance with service regulations,” Day said at the time.

The military judge in Benson’s case has yet to rule on the motion. Henderson said the trial is currently scheduled to begin in January, a date that could change.

The motion calling for the case to be dismissed accuses CNO Richardson of “abuse of the military justice process” and contends that he and the Navy’s other top officers should have known their comments would corrode the presumption that Benson was innocent until proven guilty in a court of law.

It also alleges that Richardson picked one of his staff members — Adm. Frank Caldwell — to serve as the Navy’s disciplinary authority in order to give CNO cover, “ensuring ‘accountability’ would not rise to senior Navy leadership.”

Henderson suggests that Benson’s prosecution is a response to public and political pressure on senior Navy leaders, a squeeze that grew tighter after a second warship — the destroyer John S. McCain — collided with the Liberian-flagged merchant vessel Alnic MC on Aug. 21, 2017, killing 10 more sailors.

At first, the Navy announced that Benson could face trial for negligent homicide, but officials dropped that charge earlier this year.

Instead, he’s charged with dereliction in the performance of duties through negligence resulting in death and improper hazarding of a vessel.

The filing states that Benson was taken to Admiral’s Mast and received non-judicial punishment, or NJP, for the same charges a few days before the McCain collision on Aug. 21, 2017.

That punishment was overseen by Vice Adm. Joseph Aucoin, then-commander of the Japan-based 7th Fleet, who was fired shortly after the proceeding.

The initial probe in the Fitz disaster recommended no further investigation, Richardson signed off on Benson’s NJP and “no reviewing official recommended additional or different punishment,” Henderson wrote in the motion.

Although there was a condition attached to Benson’s NJP that permitted officials to reopen his case pending further investigation or endorsement, that never happened, according to the filing.

“Instead, the only subsequent event was yet another collision in Seventh Fleet, which once again exposed endemic problems in the Navy’s force generation model,” Henderson wrote. “By statute and regulation, CNO is the person responsible for these issues.”

In May, Navy spokesman Day said any earlier administrative actions “are separate and distinct from the ongoing criminal proceedings.”

But Henderson’s motion pointed to the subsequent McCain collision and a corresponding cascade of comments from Richardson and other top leaders blaming Benson for the Fitz debacle.

During a January all hands call at the Pentagon, a surface warfare officer asked Richardson “how a mid-level officer could feel comfortable or want to stay in the Navy given leadership’s attitude toward mistakes, as demonstrated by the Fitzgerald and McCain cases.”

“If you had seen the evidence that I saw in those cases, trust me, it was negligent,” Richardson replied, according to Henderson’s motion.

During a Nov. 2, 2017, press conference, Richardson said that “we found the commander (sic) officers were at fault, the executive officers were at fault.”

On Jan. 15, three days before Richardson would testify before lawmakers on Capitol Hill, charges were preferred against Benson and five other Fitz and McCain sailors.

“After preferral of court-martial charges, which Congressional oversight committee members applauded, CNO continued to make public statements blaming the ships’ crew and pursued information justifying charges against them while he, VCNO, and (Caldwell) pressed a media campaign that included a thinly-veiled allegation that CDR Benson would not accept responsibility for his ship,” Henderson wrote.

After his Jan. 18 testimony, Richardson told reporters that “with respect to the proximate cause of the collisions, there was nothing that was outside the commanding officer and crews’ span of control,” according to the filing.

To Henderson, those words went too far because CNO and the Navy’s other top officers “knew the limits of a commander’s license to comment on an accused’s guilt" and not one of them “can claim ignorance.”

While Richardson was playing up the guilt of Benson and his crew, he was playing down the systemic problems in the 7th Fleet that contributed to both collisions, Henderson argued.

Henderson pointed to the initial probe into the Fitz calamity by Rear Adm. Brian Fort, which delved more deeply into systemic issues that led to the disaster.

But a “woefully misleading” report released by Richardson after the McCain ignored these findings, “pushing blame downward,” Henderson wrote.

“CNO’s version of the investigation did not mention any of RDML Fort’s findings as to Fitzgerald’s manning, training-and-certification, or maintenance deficiencies,” the motion states. “The CNO’s version conspicuously omits all institutional errors that saturated the (initial) investigation — ones that Congress and others rightly laid at the feet of CNO, consistent with his statutory and regulatory obligations.”

The filing questions why some unclassified portions of a comprehensive review undertaken after the McCain collision were not released to the public, particularly findings touching on the operational demands and leadership priorities for 7th Fleet cruisers and destroyers, aspects that placed blame “squarely at senior Navy leadership.”

Richardson’s “version of the collision” released last fall slammed the crews of the ships and began what Henderson characterized as a PR blitz by the Navy that hammered this message, according to the filing.

RELATED

“After his public affairs arm reiterated this message, CNO went before the media and again deflected blame from himself and heaped it on the ships’ commanders,” Henderson wrote.

Henderson argues that Richardson kept heaping blame on Benson even after CNO knew a court-martial case might be opened against him.

“Most (comments) occurred when he knew it was likely, and all were effective uses of the media to carry the Navy’s message — which the media has done, non-stop, since last August,” the filing states. “Throughout, that message was clear: CNO blames CDR Benson for the collision of his ship.”

Navy leadership “spent months testifying, briefing reporters, the public and the Fleet, and issuing official statements all blaming Fitzgerald’s collision on her commanding officer — even after reopening (Benson’s) completed case,” Henderson wrote.

“Evidence of actual unlawful influence drips from the Navy’s concerted, unrelenting, unprecedented campaign to pin the Fitzgerald collision on CDR Benson—both to justify re-disposition of his case and to ensure that the Fleet and public know his guilt,” the filing states.

RELATED

Behind the scenes, Richardson was not only orchestrating a symphony of blame about Benson but also making sure a loyal subordinate would keep any culpability from percolating to the CNO level, Henderson’s motion contends.

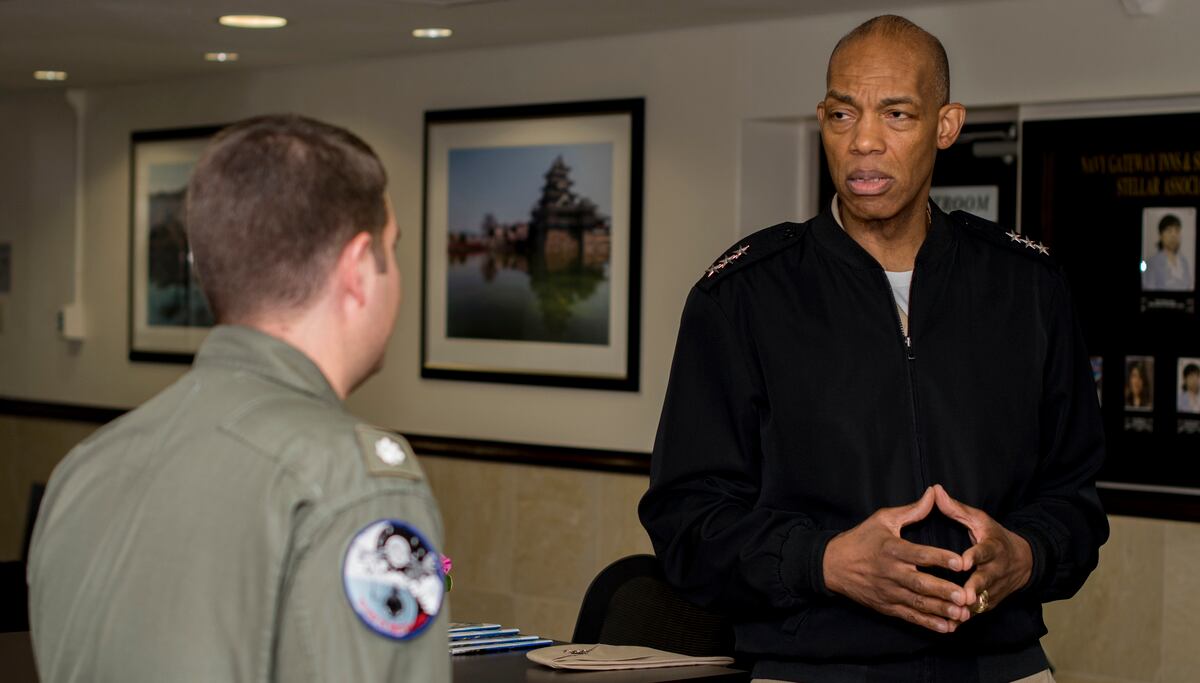

After the McCain disaster, Richardson appointed a staffer, Adm. Caldwell, the head of Naval Nuclear Reactors, to serve as the arbiter of discipline for both collisions as a “consolidated disposition authority,” or CDA.

But Richardson kept making comments about Benson’s culpability for the Fitz collision, boxing in Caldwell or any other staffer who could halt Benson’s court-martial, Henderson wrote.

“Under these circumstances, no member of CNO’s staff could independently review the evidence and make a decision that contradicted CNO’s widely-known beliefs,” Henderson wrote.

Eleven days after Richardson’s Nov. 2, 2017 statement about Benson’s culpability, Caldwell drafted a memorandum for the record “disclaiming the impact of CNO’s comments on his ‘independent discretion,’” Henderson wrote.

Caldwell’s memo aimed to “insulate himself,” and was a “thin sterilization attempt” at independence that failed to recognize “that the CDA’s authority to review the case depended on CNO," and that "the Navy media campaign began long before the press conference, and that it would not stop after the memo,” Henderson wrote.

Henderson’s filing also claims that Caldwell, Richardson, Moran and the Navy’s then-Judge Advocate General, Vice Adm. James Crawford, all worked in concert to get the CNO’s message out to the public.

At this point, “the drumbeat from the highest levels of the Navy” blaming Benson means that no court-martial panel for the case would be “outside its earshot,” Henderson wrote.

“Appointing a new convening authority down the chain does not disinfect the court,” Henderson wrote. “Likewise, there is no untainted convening authority up the chain — just VCNO and CNO.”

“The coordinated message of blame, amidst and in response to media and Congressional scrutiny, from the highest levels of the service, was so persistent and specific that the desired outcome was clear,” Henderson wrote.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.