For nearly 350 years, no venture was as lucrative as the transatlantic slave trade.

It was the most profitable — and the most horrific — of enterprises.

In 1850 a slave acquired for $40 worth of trade goods would bring between $800 and $1,200 on the block, so a cargo of 800 slaves could add up to between $320,000 and $960,000.

Even after factoring in the cost of outfitting the ship, paying off all the labor involved in the voyage and the inevitable loss of some “inventory,” a successful slaving expedition realized a profit many times the initial investment.

Consider that $100 in the 1850s would be worth around $4,000 today, and such a venture’s allure is obvious. One trip could easily make the fortunes of the captain as well as investors, and pay the sailors far more than the paltry wages they would normally earn.

So profitable was a slaving voyage, in fact, that ship owners would often order their vessels burned after their human cargo was delivered, rather than risking seizure and prosecution by the authorities.

In 1860, for example, the 452-ton bark Sultana was deliberately burned to the waterline after it carried between 850 and 1,300 slaves to Cuba.

The captain and crew, claiming to be castaways, then caught a ride to Florida on a fishing boat.

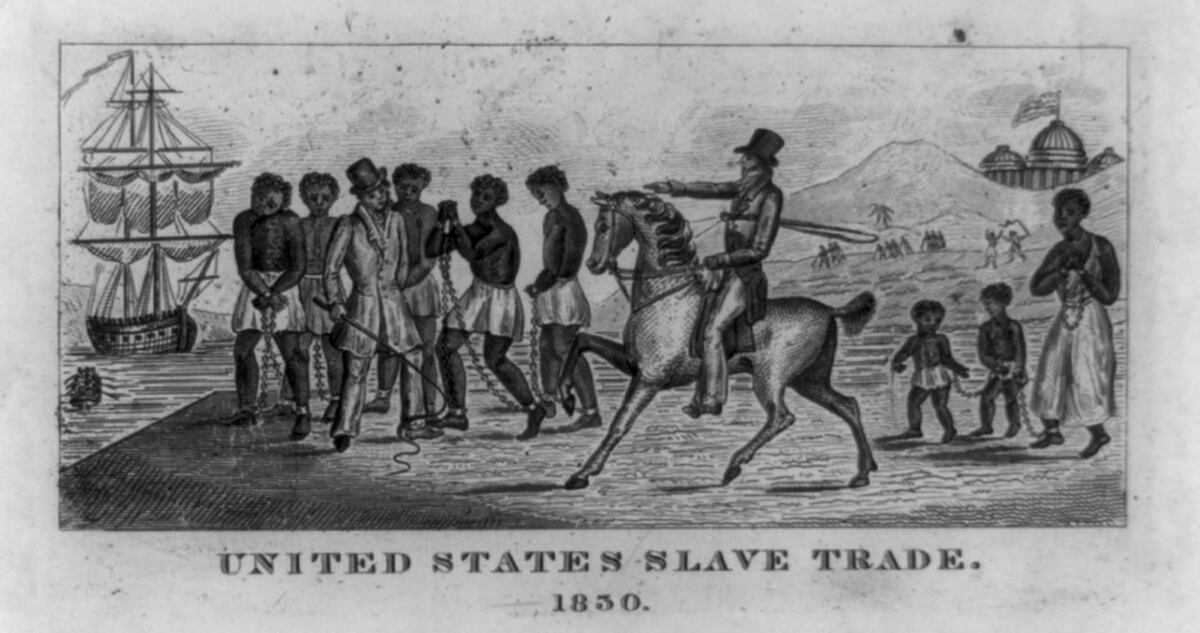

America entered the slave trade early, financing, fitting out and dispatching ships to trade for slaves along the west coast of Africa beginning in the late 1600s.

And while the South would eventually own most of those slaves, it was primarily Northern investors who financed the trips, and it was captains and crews from New York and New England who made the voyages.

In fact, for much of the early 19th century the epicenter of the slave trade in America was not Charleston, Richmond or Mobile but New York City.

Resolved to curb the traffic, the newly formed U.S. Congress passed an increasingly stringent series of laws against the slave trade, beginning shortly after President George Washington’s inauguration and culminating in the Piracy Act of 1820.

This law stipulated that any U.S. citizen serving on a foreign ship or anyone serving on an American ship that seized “a Negro or mulatto…shall be adjudged a pirate…and shall suffer death.”

But though the American government placed heavy penalties, including fines, forfeiture, imprisonment and even death on violations of the Acts, authorities did practically nothing to enforce them.

Ships sailed with impunity to Africa, loaded their holds with slaves and delivered them back to America, and also —when the Southerners of the early 1800s felt they had enough slaves — to Cuba and Brazil’s coffee and sugar plantations.

Arrests were few, convictions even fewer. No one, it seemed, wanted to kill the golden goose. In the four decades following the passage of the capital Piracy Act, only one slave trader was hanged, and few were punished at all.

America’s transatlantic slave trade flourished right into the Civil War.

The slaver has long been a subject of fascination for poets, painters and scholars. Yet there was no definitive type of slave ship.

While some were built specifically for the trade, practically any kind of seagoing vessel could be adapted to the stowage and delivery of slaves. Slave ships ranged in size from small fishing schooners to three-mast, square-rigged ships.

And with the advent of reliable steam-powered vessels in the mid–19th century, slave traders upgraded and modernized, using bigger and more capacious ships to carry their inventory.

Slavers carried as few as four or five captives, and as many as 1,000 or more, depending on the capacity of the hold, the number of decks and the “efficiency” of the ship’s master in packing his human cargo aboard.

Although few ships were built for the express purpose of hauling slaves, it was not difficult to detect a slaver.

A cursory inspection of a likely slaving vessel prior to weighing anchor for Africa would reveal provisions that far exceeded the needs of a crew of 10 or 20 men. The return voyage required food and water for a host often numbering in the hundreds.

There would be tons of grain, as well as the huge boilers known as “coppers,” in which to cook it. While some captains drew the line at feeding slaves anything besides this mush, others also provided beans, and salt pork and beef. Of course, the less spent on maintaining the captives, the greater the profit margin.

Many vessels shipped livestock as well, but this was reserved for the captain and crew; basic sustenance was the policy for the Africans.

Provision for vast amounts of water was another indicator.

It made no sense to ship water for the trip’s outward leg, so a slaver captain typically stored the barrels, broken down into hoops and “shooks,” stacked below deck.

The barrels were assembled and filled on the African Coast, often with fetid water from coastal rivers, once the slaves were purchased.

Medicine was another vital commodity. A slave ship generally carried large quantities of cures and disinfectants.

Since such vessels rarely included a doctor in the crew, the captain of necessity became familiar with a wide range of nostrums and folk remedies — not out of humanitarianism, but to ensure the loss of as few slaves as possible.

Some slave traders actually went so far as to write their own medical manuals.

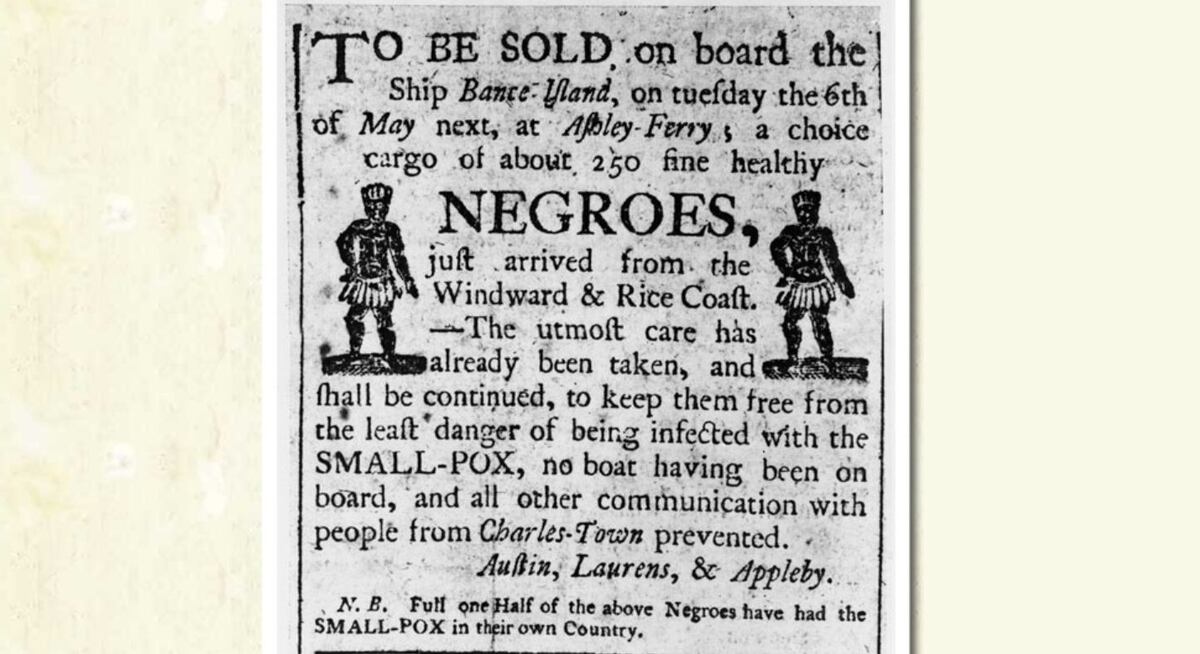

To fight disease on board (most commonly smallpox), some captains smoked their vessels in pitch, which was believed to be a preventive.

The combined stink of pitch, sweat and the human waste of captives wafting on the breeze made a slave ship a floating offense to the olfactory system. It was said that a slaver could be detected on the water several miles downwind, long before it was sighted.

Sir Dalby Thomas, commander of England’s Royal Africa Company, did not exaggerate when he pointed out in 1706: “Your captains and mates must neither have dainty fingers or dainty noses, few men are fit for these voyages but them that are bred for it. It’s a filthy voyage and a laborious [one].”

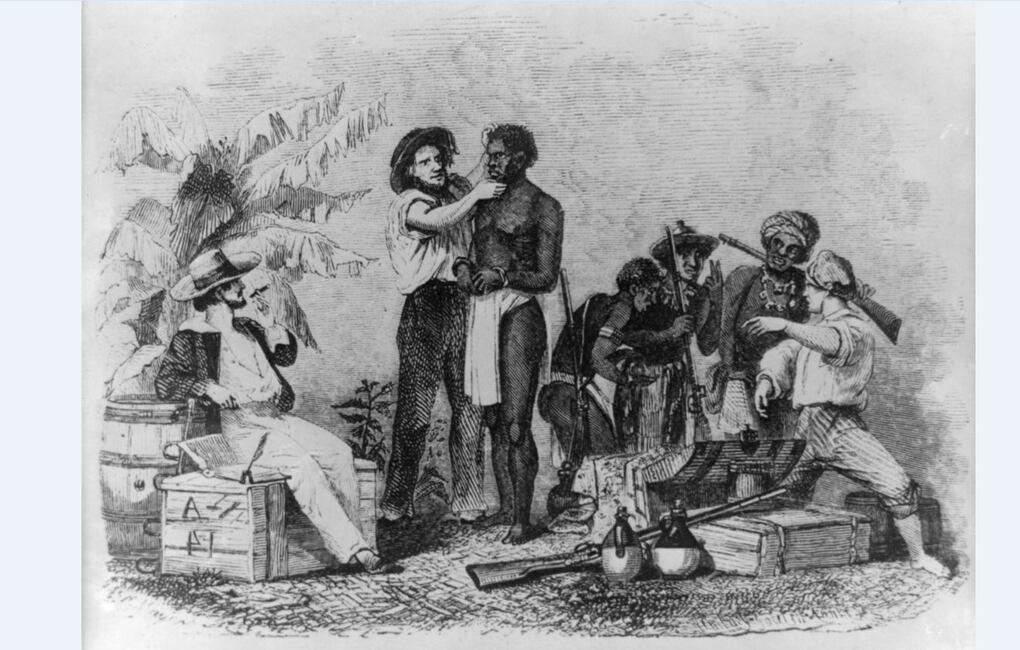

Another sign, albeit an ambivalent one, that a vessel was likely bound for Africa as a slaver was the presence on board of trade goods.

These generally consisted of calico cloth, beads, knives, guns, bars of iron stock, cigars and that commonest of trade items, liquor. A slave ship more often than not carried dozens of hogsheads of whiskey or rum.

Should he be stopped at sea, the captain could claim he was on a legitimate trading expedition, with goods to exchange on the African Coast for palm oil, ivory, gold dust, gum copal and peanuts.

Some slaver captains shipped scores of manacles, although shackles were impossible to explain away if the ship was searched en route. Most captains simply relied on their crew and weapons stored aboard to maintain order.

The captain’s cabin frequently became a virtual arsenal, bristling with cutlasses, pistols and muskets at the ready if there was an uprising.

The most obvious indication that a vessel was bound on a slaving voyage was the presence of hundreds of feet of board lumber. Once the ship was at sea or when it reached Africa, the wood was used to construct a “slave deck” about 4 feet below the main deck, running the entire length of the vessel, to accommodate confined, recumbent prisoners.

Sadly, despite the discovery of materials clearly associated with the slave trade, in case after case slaver captains and crew members were released and allowed to continue their work.

While 19th-century courts of both Britain and France had maintained that the presence of “equipment articles,” both on board and on the ship’s manifest, provided clear indication of the criminal nature of a voyage, American courts refused to allow it as proof of complicity.

Fitting out and provisioning a slaving voyage was a costly proposition, one that few captains could manage on their own.

Behind nearly every venture was an established, well-organized shadow company that provided all the necessary outfitting, from stores and provisions to the crew itself.

Much as today’s brokers sell shares to their clients, they solicited investors from the ranks of respectable businessmen looking for a huge return. The shadow company also covered the costs of paying the shipping agents and workmen, bribing customs officials and retaining a force of lawyers in the event of arrest and seizure.

Sometimes the captain was a partial owner of the vessel or an investor in the voyage; sometimes he simply worked for a salary and a percentage of the sale price of the slaves at auction.

He saw his job as merely to convey merchandise of a highly valuable and highly perishable nature to a viable market.

He was in the transport business.

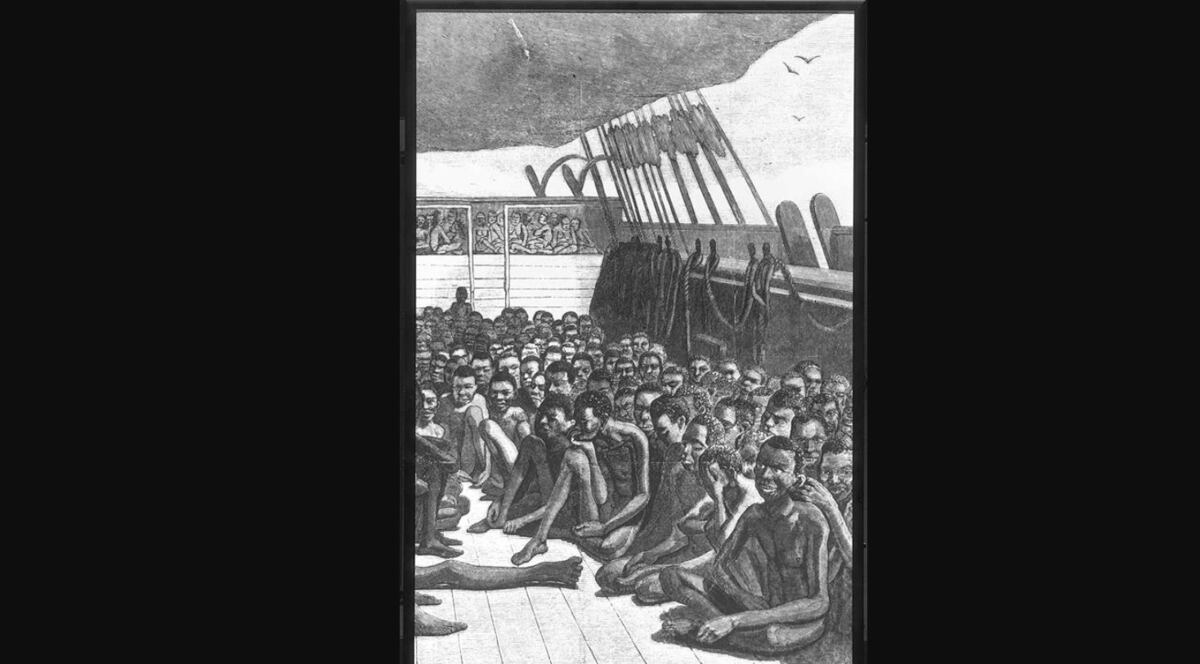

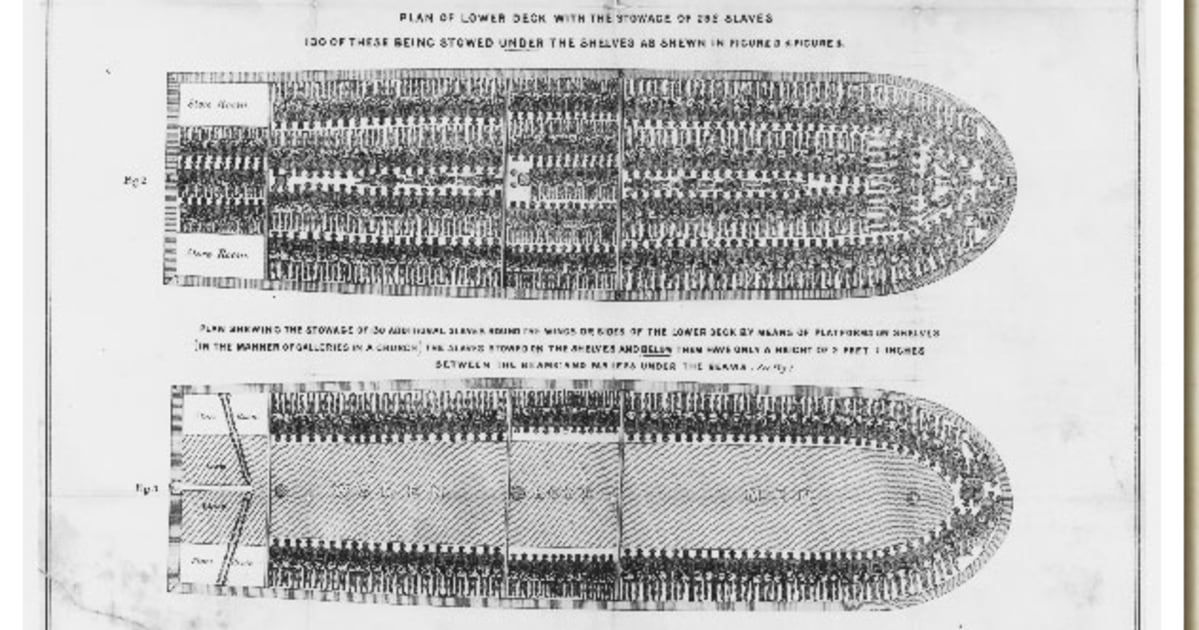

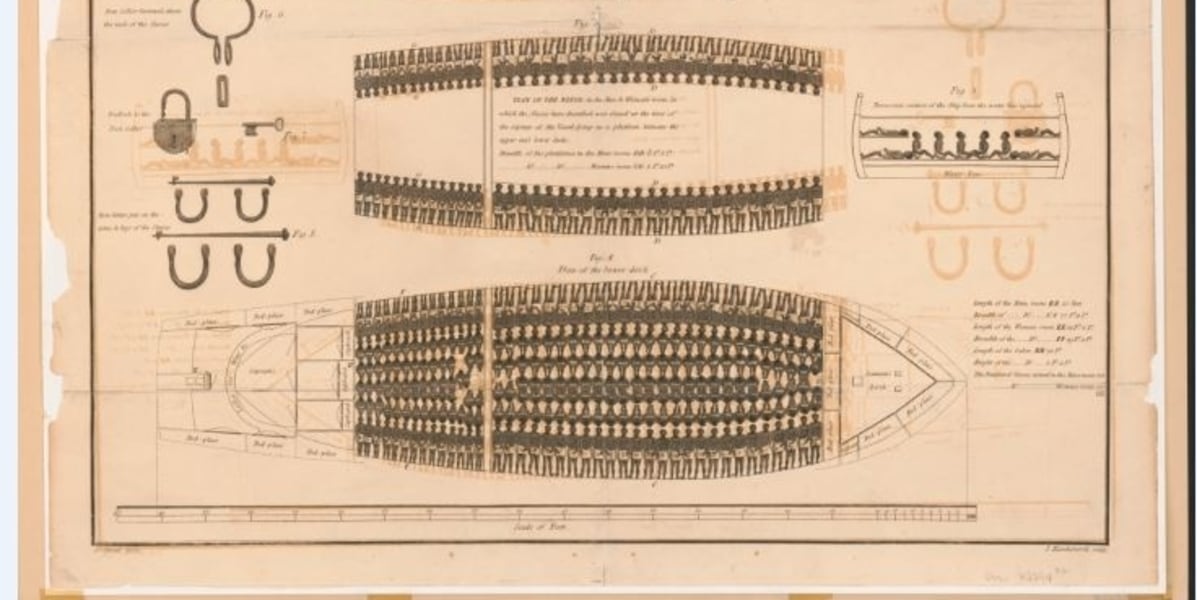

Each captain had his preferred method of stowing his charges.

Some laid the captives on their sides, with those in front and behind lying against them in spoon-fashion.

An American naval officer described one of the most common techniques, used on a vessel his cruiser had just seized.

The captain, he said, had arranged his cargo by “spreading the limbs of the creatures apart and sitting them so close together that even a foot [of a passing sailor] could not be put upon the deck.”

Another officer offered a similar firsthand observation.

The Africans, he wrote, “are packed below in as dense a mass as it is possible for human beings to be crowded; the space allotted them being…about four feet high between decks, there, of course, can be but little ventilation….These unfortunate beings are obliged to attend to the calls of nature in this place — tubs being provided for the purpose— and here they pass their days, their nights, amidst the most horribly offensive odors of which the mind can conceive, and this, under the scorching heat of the tropical sun, without room enough to sleep; with scarcely space to die in….”

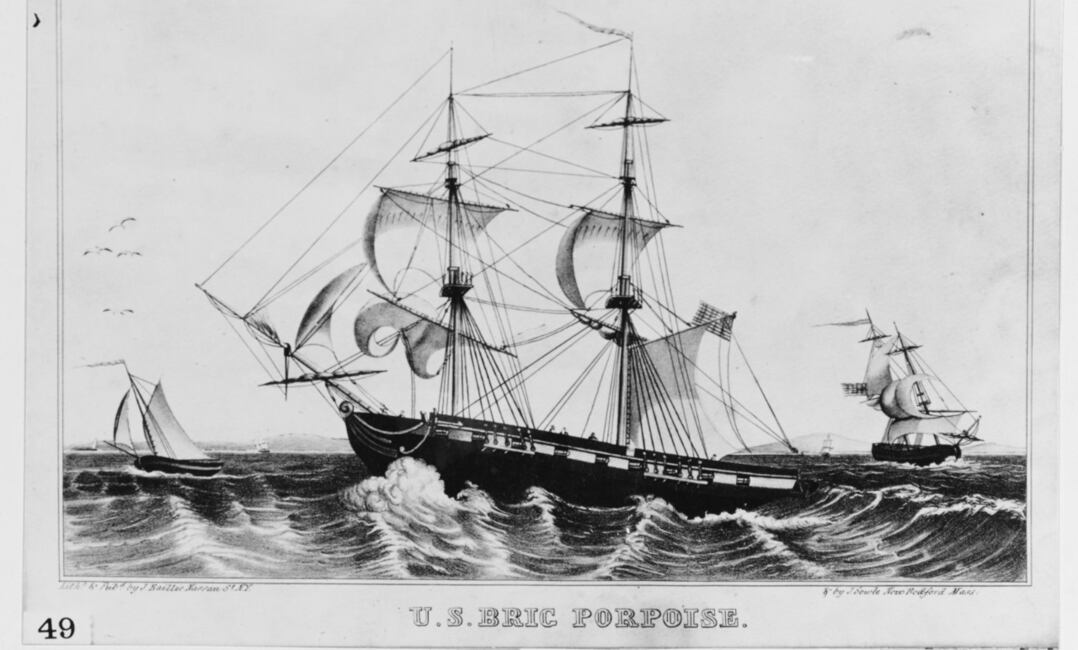

When the U.S. Navy brig Porpoise seized a slaver in 1850, Midshipman James Taylor Wood, who would achieve fame as the Confederate “Sea Ghost,” recorded his impressions:

From the time we first got on board we heard moans, cries, and rumblings coming from below and as soon as the captain and crew were removed, the hatches had been taken off, when there arose a hot blast as from a charnel house, sickening and overpowering. In the hold there were three or four hundred human beings, gasping, struggling for breath, dying; their bodies, limbs, faces, all expressing terrible suffering. In their agonizing fight for life, some had torn or wounded themselves or their neighbors dreadfully; some were stiffened in the most unnatural positions….A little water and stimulant revived most of them; some, however, were dead or too far gone to be resuscitated….

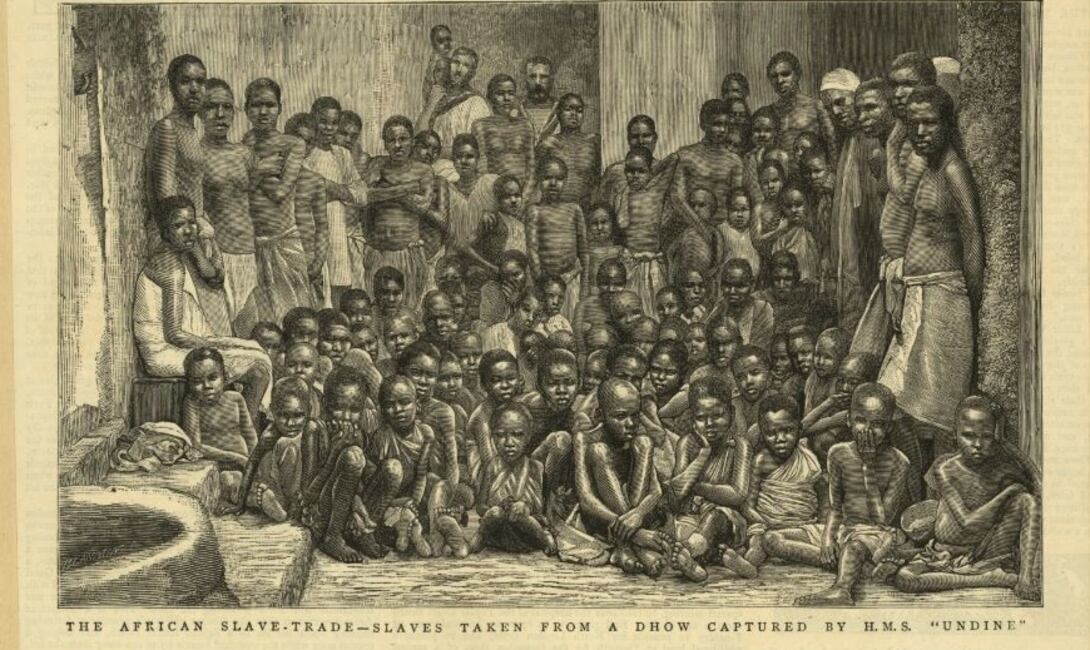

The object of any slaving expedition was to deliver as many living human beings as possible; deaths that occurred on a voyage were merely attributed to the cost of doing business.

Mortality on board American slavers varied, depending on the length of the voyage, the severity of conditions on board and the callousness of captain and crew, but it averaged 17.5 percent.

Of every 1,000 captives taken from Africa, some 175 perished on the infamous Middle Passage, the voyage from Africa to America, Brazil or the islands of the Caribbean.

They died of disease, thirst, starvation, suffocation, exhaustion, suicide and sometimes simply despair. Attempts at suicide were punished with torture and execution, as an example to the others.

So common were deaths aboard slave ships that sailors told stories of the schools of sharks that followed their vessels from Africa to their destination ports.

There are documented accounts of slave ship captains ordering their captives jettisoned. Mid–19th century British artist J.M.W. Turner gained notoriety from his shocking 1840 painting Slave Ship, also known as Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying — Typhoon Coming On, which depicts manacled slaves struggling in the storm-tossed ocean as a ship sails away.

It was not always inclement weather that led a captain to such a callous act.

On his 11th slaving voyage, when an English slaver named Homans found his brig surrounded by four British naval cruisers, he ordered all 600 manacled slaves aboard brought on deck and bound to the anchor chain. When the cruisers’ boats lowered to approach the slaver, Homans had the anchor thrown over side.

As it plummeted to the ocean floor, it carried with it every man, woman and child. Upon boarding the slaver, the British found clear evidence that hundreds of people had occupied the hold only moments before, but they were powerless to act.

They released his brig as Homans jeered at them from his deck.

The loss of a slaver’s “cargo” did not always signify the voyage was a failure. Unbelievably, insurance companies — both in America and abroad — were only too willing to insure slaving expeditions, and paid market value for the slaves so long as the loss was due to the forces of nature.

When a captain threw his charges overboard, he had to be able to defend his actions in a formal hearing before insurance investigators if he hoped to be compensated for the loss.

One slaver, denied payment on a cargo of slaves he had thrown over the side, sued the insurance company, and the courts found in his favor.

In the unlikely event of an arrest at sea, slaver captains had a proven method of evading the law.

Commonly referred to as the “Spanish Captain” defense, it was so often used in slaver cases that it became an expected legal ploy.

Because foreign nations were barred by law from boarding American ships at sea, Yankee slavers carried both legitimate and false papers, as well as the flags of various nations.

Should an American slaver captain sight a suspicious vessel bearing down on him, he first determined the nationality of the ship. If it flew a foreign flag, he’d leave the American pennant in place and assume he couldn’t be legally boarded.

But should the cruiser be flying the U.S. flag, he’d immediately lower his colors and raise a foreign flag, fetch the spurious sailing papers of that country (usually Spain or Portugal) and throw his American papers overboard.

Should the cruiser’s officers still insist on boarding his ship, he would bring forth a handful of Portuguese or Spanish nationals whose sole purpose for being aboard was to assume the roles of captain and crew.

The actual captain would then claim to be merely a passenger who had hooked a ride home from Africa aboard a slave ship.

Transparent though this defense was, it succeeded time and again for decades in American courtrooms, where judges bent the law to favor slave traders — and American juries refused to convict or hang American seamen for carrying slaves from Africa to a foreign country, when it was perfectly legal to sell and transport slaves from, say, Virginia to Louisiana or Georgia.

In only one case did the Piracy Act function as intended, and that didn’t happen until the nation was embroiled in the Civil War.

In August 1860, young sea captain Nathaniel Gordon (“Lucky Nat,” as he was called) was apprehended on open waters just two hours off the mouth of the Congo River.

Gordon was a native of Portland, Maine, who had completed at least three previous voyages, and had just traded whiskey for 897 Africans — half of them children.

After cramming them into the hold of Erie, a ship of only 122 feet, he was bound for Cuba’s slave markets when a U.S. sloop-of-war sighted him by chance and ran him down.

On first sighting the sloop, Gordon assumed it was a British ship and left his U.S. flag aloft.

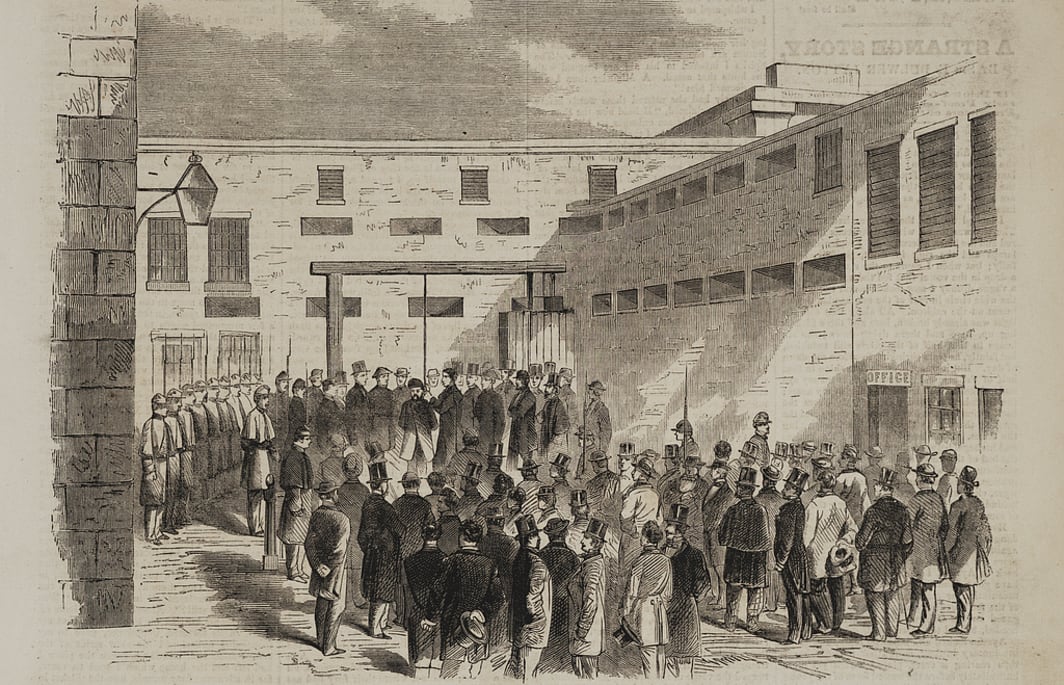

That resulted in Erie being boarded and seized, and Gordon and his two mates were subsequently taken under guard to jail, under federal indictment in New York.

As The New York Times later reported: “Had he reached the port of destination with the usual proportion of living Negroes, an immense fortune would have been made, and in that event, as he declared, he would have returned to the United States rich and contented….But it was ordained otherwise.”

At first Gordon seemed headed for an easy acquittal. New York’s courts had a long-standing reputation for showing leniency to slavers, and Gordon’s backers had hired some of the city’s most prominent attorneys, who were experienced in slave trade cases.

Jailers often looked the other way as accused slavers escaped, usually to return to sea.

Then too the U.S. attorney, James I. Roosevelt, had no particular interest in prosecuting slaving cases.

And if all this were not enough, James Buchanan, president when Gordon was arrested, had gone on public record saying he would never hang a slaver. Apparently Nathaniel Gordon had nothing to worry about.

Then came the 1860 election of Abraham Lincoln, and a strongly Democratic, Southern-leaning New York City found itself with a new Republican U.S. attorney, E. Delafield Smith, who entered office determined to put an end to the slave trade.

Smith made Nathaniel Gordon his personal demon. Charged under the old 1820 Piracy Act, Gordon had a veritable “dream team” defending him, but the old arguments that had for decades served to set slavers free no longer worked.

It took more than a year and two trials, but Delafield Smith won his conviction and, from a Connecticut judge trying his first slave trade case, a sentence of death.

Lincoln, already known for his merciful tendencies, was barraged with appeals to spare Gordon. The slaver’s wife and mother went to the White House to plead for his life, but the president refused to see them.

Gordon’s chief attorney, a respected former judge, visited Lincoln, but the president remained firm. Kindly though he was, Lincoln drew the line in the case of a slaver.

As he eloquently put it, “I think I would personally prefer to let this man live in confinement and let him meditate on his deeds, yet in the name of justice and the majesty of law, there ought to be one case, at least one specific instance, of a professional slave-trader, a Northern white man, given the exact penalty of death because of the incalculable number of deaths he and his kind inflicted upon black men amid the horror of the sea-voyage from Africa.”

“Lucky Nat” was hanged in New York City’s prison on February 21, 1862.

By that time the 3½-centuries-long slave trade was dying of natural causes.

Brazil had closed its ports to slave ships, and the American South was blockaded by the Union Navy.

Now, with the signing of the Seward-Lyons Treaty, Lincoln had allowed Britain’s formidable fleet to stop and board suspicious American vessels.

And except for Spain, European nations had also withdrawn from trade in human cargo.

Gordon’s fate demonstrated the new administration’s resolve to address the trafficking in humans — at a juncture when confronting the issue of slavery had become unavoidable in the United States.

Within the year, there would be no more American slave ships plying the Atlantic.

Ron Soodalter is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon: The Life and Trial of an American Slave Trader. This article originally was published in the February 2011 issue of Civil War Times, a sister publication to Navy Times. To subscribe, click here.