Although a small, dusty town where residents constantly battled heat and drought may seem an unlikely setting for a heroic effort at colony building and racial self-determination, this community of “race pioneers,” with its commitment to limiting the parameters of prejudice, served as a beacon of hope to African-Americans in the Golden State and across the nation.

The community, Allensworth, belied the notion of African-American inferiority and, in so doing, generated excitement, hope and confidence.

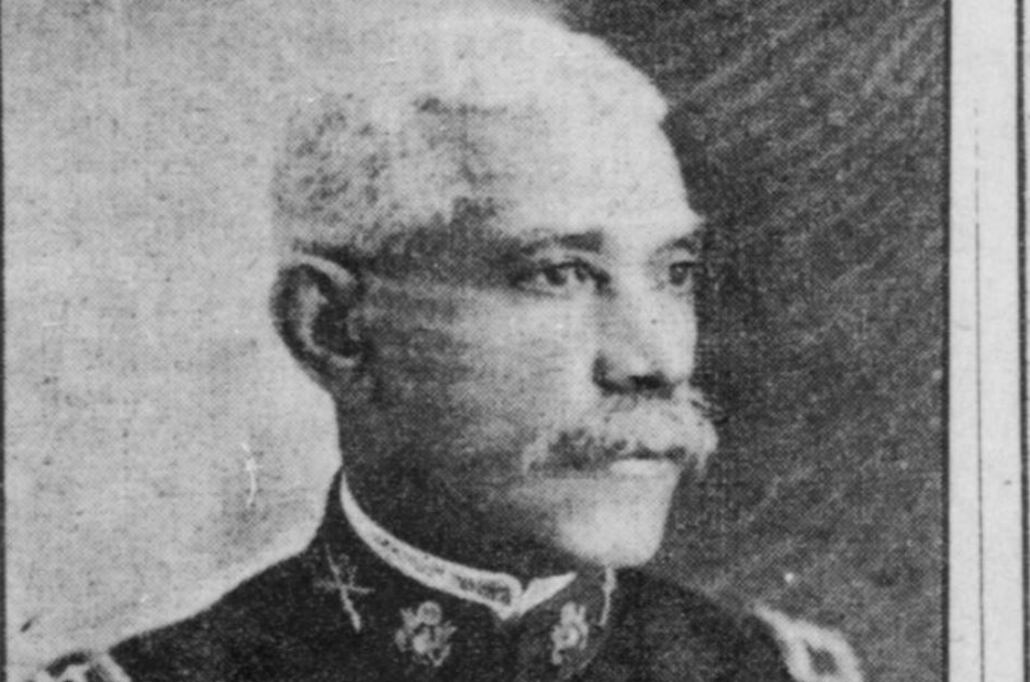

“As soon as our race gets property in the form of real estate, of intelligence, of high Christian character, it will find that it is going to receive the recognition which it has not thus far received,” said Lt. Col. Allen Allensworth, the community’s founder.

This town and its founder deserve a kinder fate than relegation to a historical footnote.

For blacks in California, the end of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th was a nadir: the U.S. Supreme court anointed racism’s handmaiden, segregation, as the law of the land; a form of economic bondage known as share-cropping re-enslaved the mass of southern blacks as well as poor whites, and the black community’s leadership was splintered by the acrimony between W. E. B. DuBois and Booker T. Washington.

It was this atmosphere of uncertainty and discrimination that encouraged five “gentlemanly looking Negro men” (so described by the Delano Holograph on June 13, 1908) to work toward the creation of a race colony in California.

Guiding his venture were the fervor and dreams of Allen Allensworth.

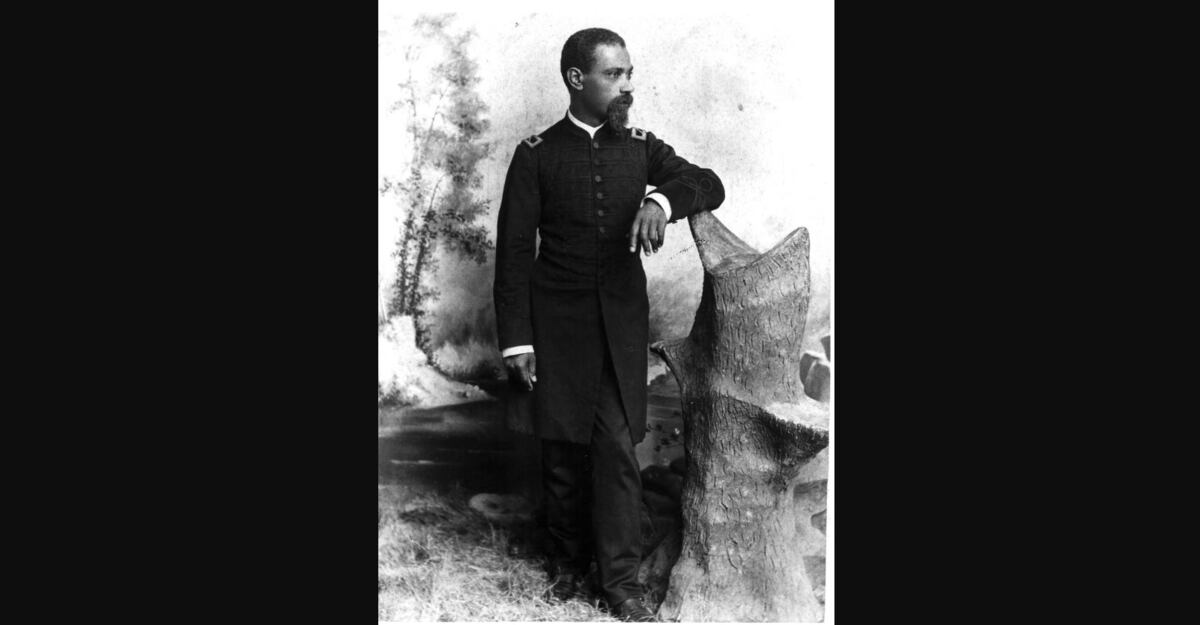

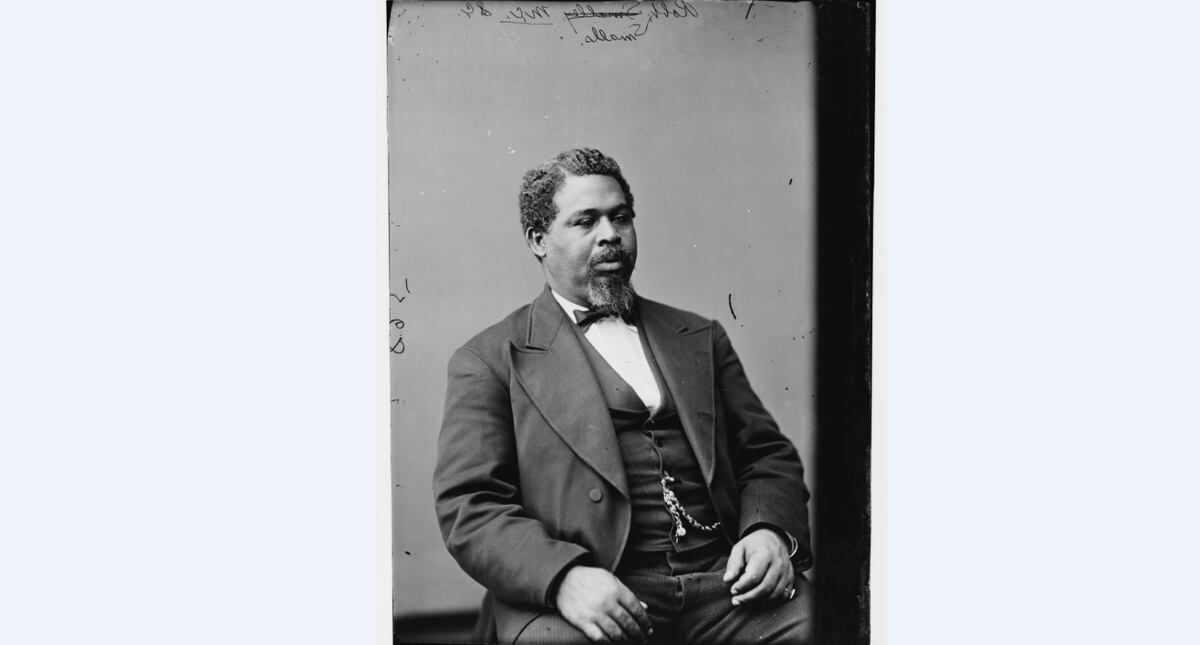

Although born into slavery in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1842, Allensworth refused to submit to that degrading institution.

During his youth, despite laws forbidding the education of slaves, Allensworth mastered reading and writing, whetting his lifelong appetite for learning.

After two unsuccessful escape attempts, he finally succeeded during the initial years of the Civil War. Recognizing the importance of that struggle, Allensworth wanted to participate.

For several months in 1862, the former slave worked as a civilian aide to the 44th Illinois volunteer Infantry. But this service did not satisfy Allensworth.

On April 3, 1863, he became a seaman, first class, of the Union Navy.

During the remaining years of the civil war, he served on gunboats such as the Queen City and Pittsburg.

He left the navy in April 1865 with the rank of first class petty officer.

During Reconstruction, Allensworth underwent a religious conversion and decided to study theology at Roger Williams University in Nashville, Tennesse.

While at the university, he met and later married Josephine Leavell.

After completing his studies, Allensworth maintained several pulpits in and around his native Louisville.

“Allensworth’s success as a minister propelled him into politics,” says Stanleigh Bry, library director for the Society of California Pioneers.

He was one of Kentucky’s delegates to the Republic National convention in 1880 and 1884.

It was in 1882, however, that a black soldier came to Allensworth for help, complaining about the lack of black chaplains in the all-black military units.

“The soldier urged Allensworth to help recruit blacks to fill those positions. But Allensworth did more than recruit,” Bry says. “He decided to become a chaplain himself.”

Reportedly, Allensworth hoped that as a chaplain, he could improve the lot of the average black soldier, help the race in its battle to win support and, at the same time, provide a secure future for his family.

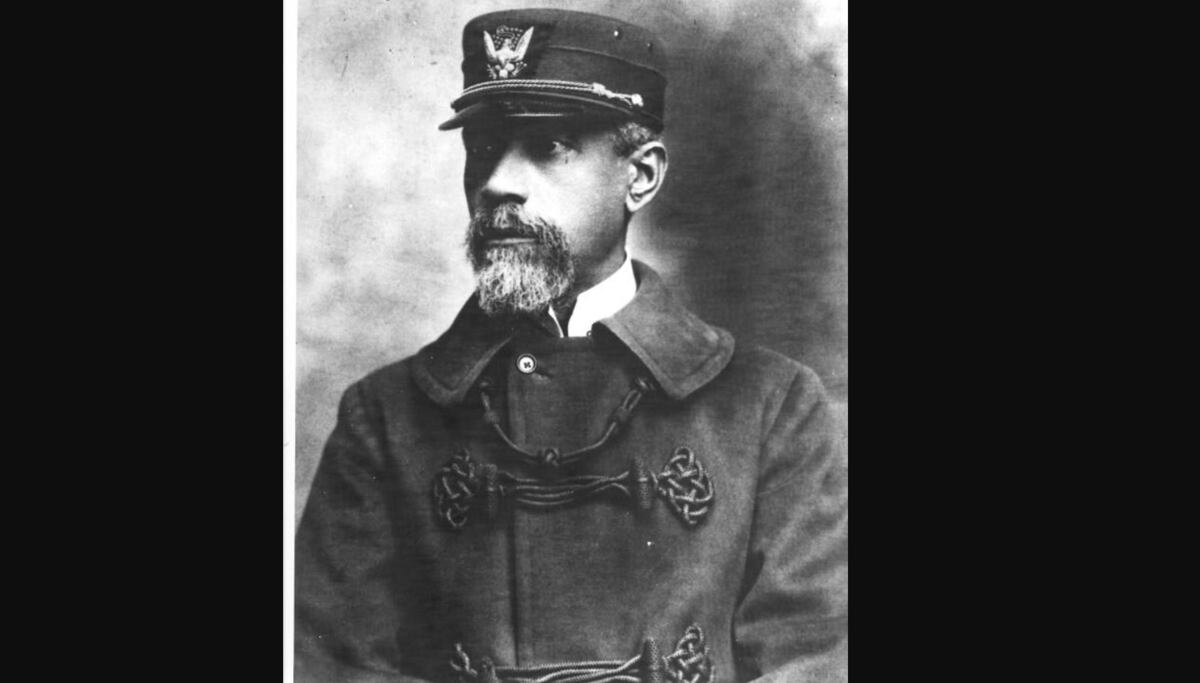

Thus motivated, Allensworth launched a concerted effort to gain appointment to the 24th Infantry (colored) in 1884.

First, Allensworth solicited testimonials and letters of support from a myriad of major and minor southern politicians, Democrats and Republicans alike.

Then he drafted letters to President Grover Cleveland and to the Office of the Adjutant General.

In these missives, Allensworth crafted a persuasive argument. He reasoned to Cleveland that by appointing a black chaplain, “the president could strengthen [his] administration among the colored people, particularly in the South.”

He also stated that he could be of service in securing good discipline and gentlemanly conduct among the soldiers.

Finally, ever the pragmatist and fully aware of the reservation about social interaction between black and white officers, Allensworth wrote, “I know where the official ends and where the social life begins, and therefore [guard] against social intrusion.”

Allensworth’s considered exertions were rewarded: in April 1886, he was appointed chaplain of the 24th Infantry with the rank of captain.

For 20 years, Allensworth ministered to the needs of his flock as the 24th moved from Fort Apache in the Arizona Territory to Camp Reynolds in California to Fort Missoula in Montana.

When he retired in 1906, Lt. Col. Allensworth and his family relocated to Los Angeles. But an ordinary retirement was unthinkable for this man, so involved with the struggle to improve the position of blacks.

Not least among the motives of the “Colonel,” as he became known, was his desire to change white attitudes toward blacks.

Rather than spending his golden years in the California sunshine, Allensworth continued to promote the African-American race and promulgate the teachings of another individual who had come up from slavery, Booker T. Washington.

The lieutenant colonel, an ardent supporter of the Tuskegean, believed that if the race was to rise, blacks had to be willing to do for themselves, to rely on black self-help efforts, rather than on white philanthropy.

Allensworth was particularly fond of one admonishment published in the California Eagle by its editor, J. J. Neimore: Eschew cheap jewelry. Quit taking five-dollar buggy rides on six dollars a week. Don’t put a five-dollar hat on a five-cent head. Get a bank account. Get a home of your own. Get some property . . . Don’t be satisfied with the shadows of civilization; get some of the substance for yourself!

This statement is also credited to Booker T. Washington.

To spread these and other ideas, Allensworth embarked on a speaking tour to inspire and educate blacks.

Presenting lectures entitled the “Five Manly Virtues Exemplified," the “Battle of Life and How to Fight It,” and "Character and How to Read It”, the lieutenant colonel sought to encourage thrift, instill the value of education, and plot a strategy whereby the whole race might uplift itself.

Allensworth’s ideas, however, were restricted to theoretical discussion on the lecture circuit, until he met William Payne, a gifted teacher and university graduate living in Pasadena, California.

Although different in age and temperament, Payne and Allensworth were kindred souls in the struggle to improve their race.

Payne, a graduate of Denison University and a West Virginia native, had spent his youth in Corning, Ohio.

Before settling in Pasadena in 1906, he had been an assistant principal at the Rendsvile School and a professor at the West Virginia Colored Institute.

Arriving in California, however, Payne soon discovered that if black teachers were rare, jobs for them were even rarer.

Recognizing the need for unusual measures, Allensworth and Payne plotted the creation of an all-black community — a colony of orderly and industrious African Americans who could control their own destiny.

The two men believed that in such a community, free of the debilitating effects and limits of racism, blacks could demonstrate that they were capable of organizing and managing their own affairs.

“The colony would prove to all Americans that black people were worthy of their rights and responsibilities as citizens,” says Bry.

The soldier and the scholar envisioned a black community that would make opportunities for African-Americans — opportunities being central to the philosophies of both men. They believed that the disappointing status of the race nearly half a century after emancipation was due to circumstance rather than color.

Yet most of the country, then imbued with the wisdom of eugenics (the science of selective genetics), believed that blacks were intrinsically inferior and therefore incapable of contributing to the American nation of its road to greatness.

White Californians, of course, held this same belief.

Payne and Allensworth believed that given the opportunity, blacks could live up to their potential, and in the process, destroy that malicious fallacy. Their colony, they believed, would provide that very opportunity.

“Allensworth, California, belied the myth of African-American genetic inferiority by providing the opportunity for hardworking, orderly black Californians to control their own destiny,” says Michael Harvey, chief librarian for the California Historical Society.

Another function of the colony that would eventually become Allensworth was to provide a home for the soldiers of America’s four all-black regiments.

Obviously, this meant much to the lieutenant colonel. In his promotional newsletter The Sentiment Maker (May 1912), the needs and desires of the soldier were stressed throughout.

Headlines regarding “Home, Sweet Home” called out strongly to the wander-weary military men and their families.

In Allensworth, it was promised that every man would have a good home.

“For a small outlay of your present pay,” Allensworth said, "you may become independent, yes, even a richer soldier-gentleman, surrounded by people of your own kind, your own sort. "

As a final inducement, he promised that the community would eventually possess a home for soldiers’ families.

There, soldiers could leave their families in a beautiful balmy California climate, surrounded by the very best environment, while overseas on hazardous duty.

In short, life in their colony, for the soldier, would be a reward for a job well done.

As the mechanism to transform their ideas into reality, on June 30, 1908, Allensworth and Payne created the California Colony and Home Promoting Association, with offices in the San Fernando Building on Main Street and in downtown Los Angeles.

Although Allensworth and Payne were the chief officers of the association, several others also played a significant roles in the colony’s founding: John W. Palmer, a miner; William H. Peck, a minister; and Harry A. Mitchell, a real estate agent.

The association soon ran into difficulties, however, in the problems and expenses of acquiring choice land for a black settlement, and it seemed that the venture might flounder until, as one contemporary put it, the Pacific Farming Company came to the rescue.

This white-owned rural land development firm offered the association prime land in Solito (or Solita, as it was spelled on Santa Fe Railroad schedules), a rural area in Tulare County 30 miles north of Bakersfield.

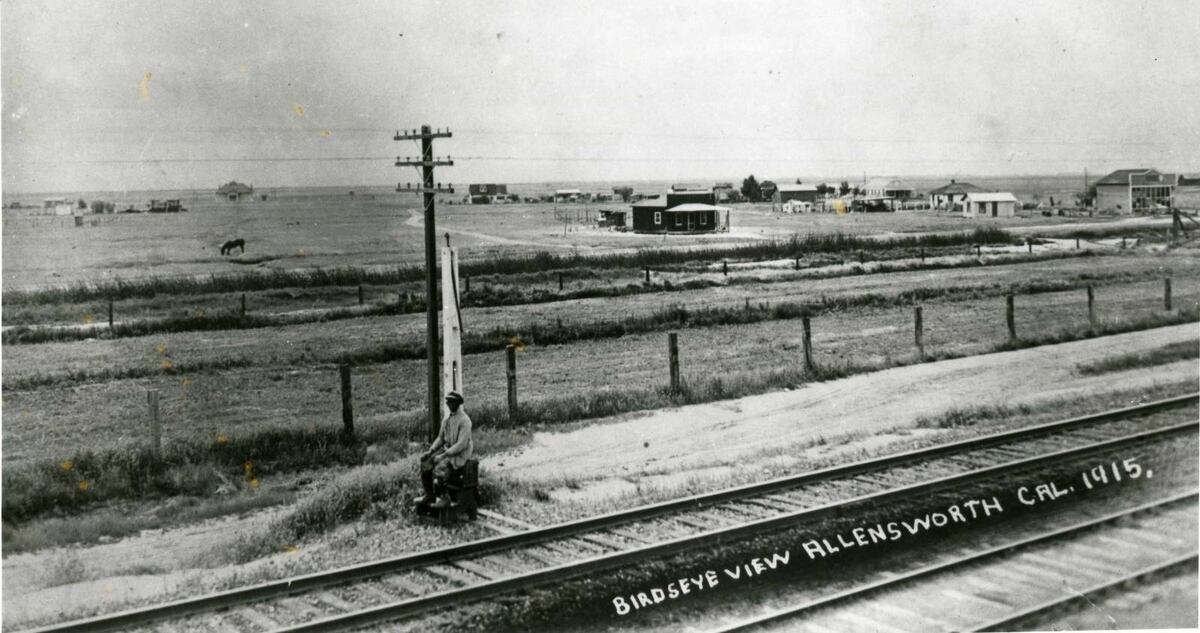

Quickly renamed Allensworth in honor of the retired officer, Solito/Solita was a good site for the colony. It was a depot station on the main Santa Fe Railroad line from Los Angeles to San Francisco, the soil was fertile, the water seemingly abundant, and the acreage not only plentiful but also reasonably priced.

Initially, many of the colony residents, including Allensworth, were surprised but gratified that a white company had come to their aid.

Yet within five years, the Pacific Farming company would become the colony’s adversary in a water controversy.

Its incorporation papers state that the Pacific Farming Company was organized in 1908 to develop rural land into town and village sites. Led by William Loftus of Fullerton, California., and Los Angelenos J. R. Treat and W. H. Bryson, this moneymaking venture was headquartered in the Security Building at 508-510 Spring Street in the heart of the Los Angeles business district.

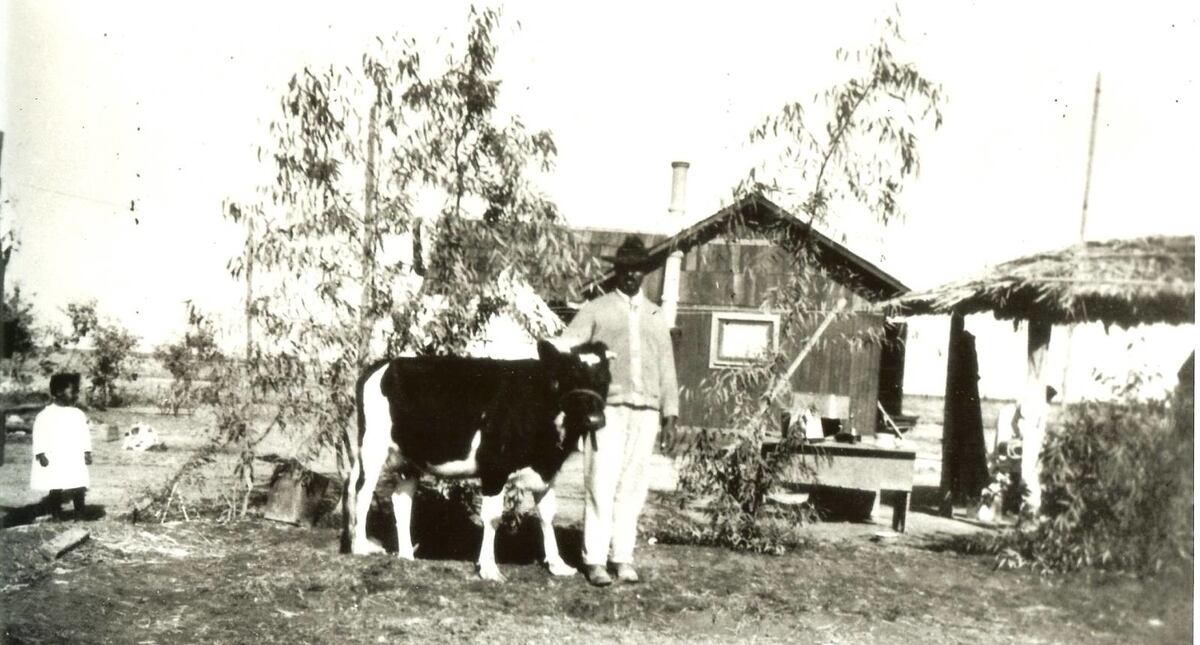

Once the deal was consummated, the association began to market the colony as a "haven for conscientious blacks who desired fertile land and a community where their exertions [would be] appreciated. "

Within a year, the Tulare County Times reported that 35 families were residing in Allensworth.

Although obtaining accurate figures concerning the early settlement is difficult, the colony generated enough excitement to attract pioneers from throughout the nation.

“The colony’s population was greater than figures listed in government records because of Allensworth’s floating population of people who would come and stay there three or four months and go and the county registrar would know nothing about it,” says Henry Singleton, a former resident of Allensworth.

Population figures are also blurred by the fact that many individuals purchased lots but lived in other areas, intending eventually to make Allensworth their home.

By 1912, however, Allensworth’s official population of 100 had celebrated the birth of Alwortha Hall, the first baby born in the town, and enjoyed two general stores, a post office, many comfortable homes, such as the one Allen and Josephine Allensworth built in 1910, and a newly completed school, the pride of the community, that also served as the center for the town’s social and political activities.

The 1912-1915 period marked the apex of Allensworth as a thriving community.

African-American newspapers throughout the nation noticed the tiny hamlet: The New York Age chronicled its growth; the Washington Bee congratulated all involved with the enterprise; and the California Eagle gleefully exclaimed that there is not a single white person having anything to do with the affairs of the colony.

Even the Los Angeles Times took note, labeling Allensworth an ideal Negro settlement.

The national black community was starved for race victories. Newspaper editors, political leaders, businessmen and educators wall were pleading for blacks to prove themselves.

In a sense, these individuals endorsed (though many did so unknowingly) the belief of W. E. B. DuBois that a “talented tenth” must lead the race to new heights.

Positive actions such as those taken by Allensworth residents were one way to portray blacks in a more favorable light.

Also during this period, Allensworth’s 200 affected the surrounding area’s economic and political structure.

“Sources such as the Oakland Sunshine [a leading San Francisco Bay area black newspaper] claim that in 1913, the citizens of Allensworth generated nearly $5,000 monthly in their business ventures,” says Jayne Sinegal, chief librarian for the California Afro-American Museum.

Furthermore, voting registration records of 1915 list an impressive array of occupations of colonists, including farmers, storekeepers, carpenters, nurses and more, all suggesting that the colony’s business and industrial output was prodigious.

Allensworth’s grain warehouses, cattle pens and storage bins served the needs of the local farmers and the railroad.

Business enterprises developed by the colonists included the large poultry farms of Oscar Overr; a 10-room, 75-cents-per-night hotel run by John Morris, that also served as a restaurant; a large general store, owned by the Hindsmon family; a cement manufacturing enterprise; plaster and carpentry shops; and sugar beet agriculture.

All this industry was geared to prove to the white man beyond a shadow of a doubt that the black man was capable of self-respect and self-control.

Politically, Allensworth became a member of the county school district, the regional library system, and a voting precinct that elected Oscar Overr the first African-American justice of the peace in post-Mexican California.

In 1914, the California Eagle reported that the Allensworth community consisted of 900 acres of deeded land worth more than $112,500.

In a strictly economic sense, this was an auspicious beginning.

Along with this burgeoning sense of political and economic influence came a true sense of community.

“It always seemed home to me,” says former Allensworth resident, Gemelia Herring. “The grass was green, and wildflowers grew all over. I thought Allensworth was one of the most beautiful places I ever saw.”

Allensworth became a town, not just a colony. This is evident in the number of social and educational organizations that existed during Allensworth’s golden age.

The Owl Club, the campfire Girls, the Girls’ Glee Club, and the Children’s Saving Association met the needs of the young, while adults participated in the Sewing Circle, the Whist Club, the Debating Society, and the Theater Club.

“The Girls’ Glee Club, modeled after the internationally known Jubilee Singers of Fisk University, was the community’s pride and joy,” says Sibylle Zemitis, a reference librarian at the California State Library.

“Organized by Professor Payne with musical accompaniment provided by the able teacher, Margaret Prince, the Glee Club traveled all over the various little white towns to sing,” she added.

Although primarily a form of entertainment, the Glee Club was also a tool used to win support for the colony.

Along with the school, the library was the focus of many community activities. From the colony’s inception, many had recognized the benefits of a public library system, and on February 2, 1912, residents petitioned the Board of Trustees of the Visalia Free Library to establish a depot station at Allensworth.

Although the request was approved, the space designated for the reading room was inadequate, so in 1913, Mrs. Josephine Allensworth, as a memorial to her mother, donated land and money to build a library that would do credit to even a larger community.

This coal box-style edifice, begun in May and completed in July 1913 at a cost of $500, had a book capacity of 1,000.

When the Mary Dickinson Library was dedicated on the Fourth of July, Allensworth immediately donated his private library to the enterprise.

As word of the library spread, Zemitis relates, the community received books from Visalia, San Francisco and North Dakota.

Tulare County supported the venture by paying the costs of a custodian for the facility, local Allensworth resident, Ethel Hall.

The library became a hub of activity as Allensworth residents, reflecting the founders’ concern with self-education, relentlessly explored its holdings.

In 1919, a local periodical noticed the community’s preoccupation with learning. The Visalia Delta, in an article headlined “Allensworth Folks Great Readers,” delineated the varied interests of the colony in books about “questions of political economy, the warring nations in Europe and those dealing with the problems and interests of the colored race in America and elsewhere.”

As with many other African-American communities in the Golden State, Allensworth’s back churches were a major factor in the development of community spirit and mutual respect.

The first Baptist Church held regular services in what was described as a neat church edifice, while the first A.M.E. Zion membership would worship in the school, and in 1916, plans were made to erect a structure for the Methodist congregation.

Another element in Allensworth’s development of the sense of communal responsibility was the struggle to establish a state-supported industrial school

Early in 1914, Lt. Col. Allensworth lobbied for an educational institute to be based on the model pioneered by Booker T. Washington in Alabama.

Allensworth envisioned a Tuskegee of the West that would provide practical training in such technical fields as agriculture, carpentry and masonry to black youths in California and the Southwest.

“When a bill to create the school was introduced in the California State Legislature, the colony of Allensworth anticipated an exciting and prosperous future,” says Michael Harvey.

It seemed that Allensworth would, as claimed by author Delilah Beasley, “become one of the greatest Negro cities in the United States,” if not the world.

But it was not to be. Lt. Col. Allensworth and Payne had been duped by the Pacific Farming Company, and let down by others.

Almost immediately, the Allensworth colony faced several crises that led to its eventual decline.

In 1914, the Santa Fe Railroad, never a supporter of this black community, built a spur line to neighboring Alpaugh, thus allowing most rail traffic to bypass Allensworth and depriving the town of the lucrative carrying trade.

The Santa Fe’s decision was the culmination of a series of conflicts between Allensworth and that railroad — and racial prejudice.

Initially, the rail line refused to change the name of the depot from Solito/Solita to Allensworth.

In an article in the Tulare County Times in July 1909, officials argued that the new name was too long to fit on signs or in the book of schedules.

“It was several years before the company relented and changed its policy,” says Herring.

A more serious problem was the Santa Fe’s employment practices.

“The corporation refused to hire African-Americans as the manager or as ticket agents of the station located in the colony and, despite repeated letters and recriminations, the railroad continued to restrict block people to menial labor,” says Sinegal.

Further, the dream of having the Tuskegee of the West ended when the bill to create the school failed to pass the legislature.

“It went down in May of 1915, partly because of strong opposition from the African Americans in Los Angeles and San Francisco, who believed that a Tuskegee-like institution would implicitly sanction and thereby reinforce educational and residential segregation,” says Bry.

Moreover, the community continued to reel under the long-standing water problem.

As part of the initial purchase, the Pacific Farming Company had agreed to supply sufficient water for irrigation, regardless of how large the town grew, but as early as 1910, the Pacific Farming Company was failing to honor its commitment.

Eventually, the community sought and gained legal redress: the control of the Allensworth Water Company passed to the town. But it was a pyrrhic victory at best because the town now owned an outdated water system, and had the unexpected burden of massive, unpaid taxes.

Not until 1918 was the community able to rid itself of the tax burden and begin to upgrade the pumping machinery, but by then the water table had dropped too low and the equipment was ineffective.

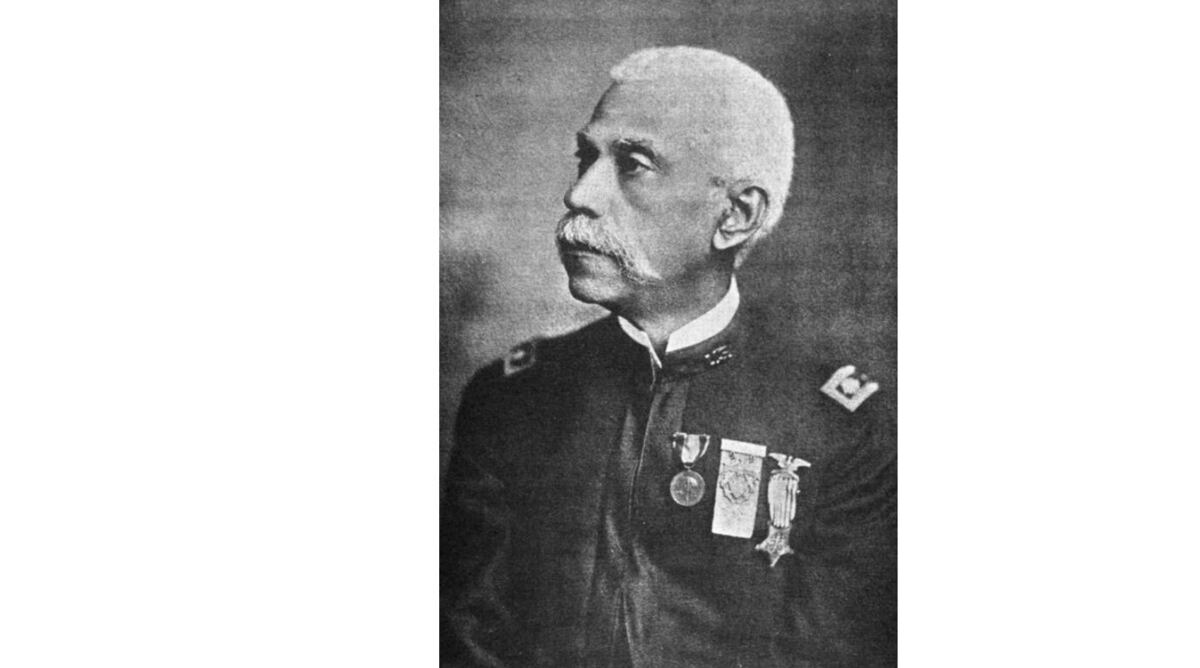

But the single most critical factor in the community’s decline was the death of Allen Allensworth in 1914.

On September 13, Allensworth was in the foothill city of Monrovia to speak at a church. Shortly after he left the train station, crossing the street, he was struck by a speeding motorcycle and died the next morning.

Riding the motorcycle were two white youths, E. S. White and W. F. Ray, who claimed that an excited Allensworth was responsible for the accident. But after the lieutenant colonel’s family filed a legal complaint, the two were arrested in late September.

After funeral services at the Second Baptist church of Los Angeles, with a military honor guard of both races, Lt. Col. Allensworth was interred at the Rosedale Cemetery on September 18, 1914.

The Allensworth community was devastated.

Although Payne and Overr assumed the leadership of the colony, no one could replace the lieutenant colonel.

Without Allensworth’s spiritual guidance and leadership, the community began to disintegrate. By 1920, the two leading figures, William Payne and Josephine Allensworth, had left the area. Payne accepted a teaching job at El Centro, while Mrs. Allensworth returned to Los Angeles to live with her daughter, Nella.

The exodus continued during the years of the Great Depression and World War II.

Henry Singleton painted a bleak and disappointing picture of the community’s decline during this period: “Any Negro that wanted to work in plowing, in potatoes or the grapes grown in Delano could just move into Allensworth, move into one of the empty homes. They could stay, no rent, no nothing, nobody owned it. Some of the houses were good, others were falling down. It was a sort of a camping ground.”

The lure of jobs in Oakland and in other war industry sites further decimated the town’s population, and in 1966, arsenic was found its water supply.

This seemed to sound the death knell for Allensworth. Yet the lieutenant colonel’s dream would not die.

Beginning in 1969, various community organizations, led by Ed Pope and Eugene and Ruth Lasartemay, expressed interest and support in creating a state historic site at Allensworth.

By 1973, the state had acquired the land, and the advisory committee, under the direction of Dr. Kenneth Goode, began its work. In May 1976, the state Department of Parks and Recreation approved the plans to develop the park, and on October 6, 1976, the park was indeed dedicated.

So Allenswoth’s dream, if not his colony, endures.

When the Department of Parks and Recreation was collecting oral histories during the 1970s as a prelude to establishing the park, however, several of the former residents who were interviewed wondered why anyone was interested in Allensworth.

After all, hadn’t the colony failed? Why commemorate an unsuccessful venture?

While the colony existed as symbol of hope for less than 20 years, it assumes greater significance in the context of the political and racial pre-World War I America.

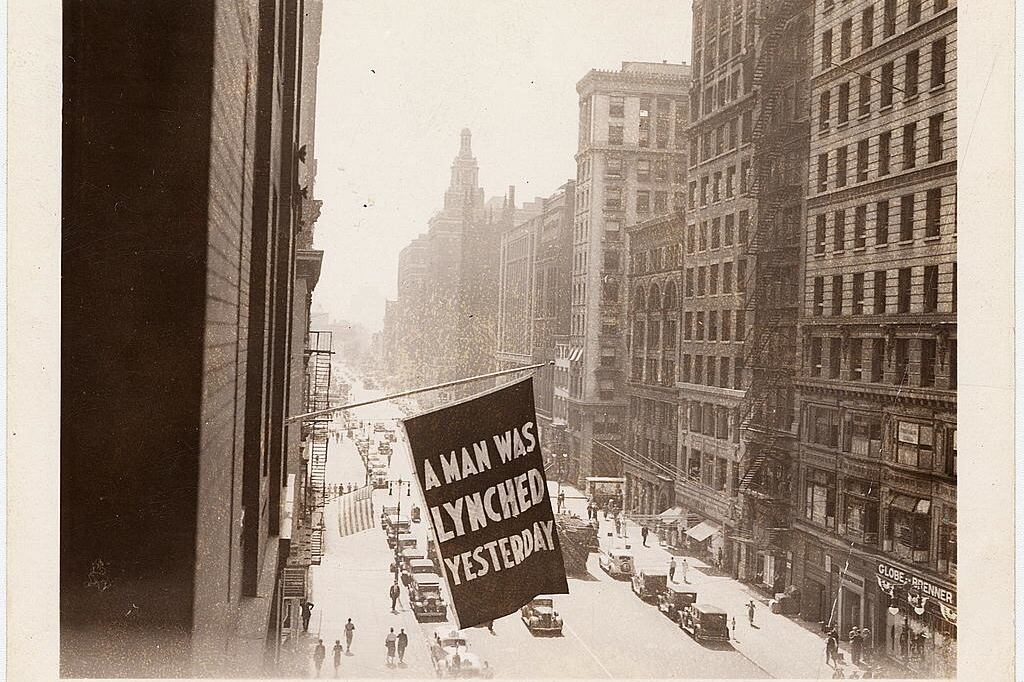

From that era of segregation, characterized by vitriolic racism and the extralegal atrocities of Judge Lynch, arose the ambiguous leadership of Booker T. Washington.

His policies of accommodation to white racism, mixed with his exhortations for black self-help and virtuous living, were clarion calls for much of the African-American community.

Certainly many early Allensworth residents agreed with Washington when he said: “One farm bought, one house built, one home sweetly and intelligently kept, one man who is the largest taxpayer or who has the largest banking account, one school or church maintained, one factory running successfully, one garden profitably cultivated, one patient cured by a Negro doctor, one sermon well preached, one life clearly lived, will tell more in our favor than all the abstract eloquence that can be summoned to plead our cause.”

The community of Allensworth was an indirect result of Washington’s philosophy of racial self-help. There, black men and women who controlled their land and destiny could prove to white America than, left to their own devices, they could create businesses, churches and communities that would contribute to black America’s rise to greatness.

Allensworth also had a role in the historical continuum of all-black towns.

While most African-Americans have always believed that hard work, perseverance and education would eventually lead to the triumph of justice and racial equality, if not for them, then for future generations, other African- Americans have been less optimistic.

The later African-Americans doubted that a nation that had spawned the Ku Klux Klan and limited its black citizens’ opportunities by legislative and de facto discrimination would ever embrace the black man and woman as an equal.

To some, the only hope lay in distancing themselves from whites. For example, individuals such as Paul Cuffee (18th century) and Bishop Henry Turner (19th century) urged African Americans to return to Africa, where one could develop one’s talents to the fullest as well as reaffirm ties to the African heritage.

But such African repatriation plans met with limited success, for the simple yet powerful reason that most black people viewed American, not Africa, as their homeland and so greeted attempts to create African-American towns within the continental United States with much more enthusiasm.

Black settlements have appeared on the American landscape since the colonial era, an example of which is the community of Parting Ways in Massachusetts.

Like Allensworth, Parting Ways and countless other all-black communities were a response to overt racism: they were heralded by the black press as a positive step forward; were greeted with distrust and at times hostility by the neighboring towns; were begun with enthusiasm and pride, but with little capital; and almost all have been forgotten.

Allensworth, California, differed from other all-black towns in its sense of mission and use of those modern promotional tools previously described.

Payne and Allensworth had hoped that by giving their town the widest possible national circulation, their thriving city on a hill would eventually change the attitudes of white America.

Thus the community tempered individual gain with the need t uplift the African-American race. And that is surely worth commemorating.

One might just as well wonder why Americans commemorate the failed defense of the Alamo, for the fact that Allensworth ultimately failed is not the most important fact about the venture.

What mattered then is that the attempt was made.

And what matters now is that all Americans finally discover the depths of character and vision of those who, through their attempt to build a colony, tried to provide an opportunity for men and women to transcend race-based limits, and thus control their own destinies.

RELATED

This article was written by B. Gordon Wheeler and originally appeared in the February 2000 issue of Wild West, a sister publication of Navy Times. His Black California: The History of African-Americans in the Golden State is suggested for further reading, along with The Black Infantry in the West, 1969-1891, by Arlen L. Fowler; The Battles and Victories of Allen Allensworth, by Charles Alexander; and The Negro Trail Blazers of California by Delilah Beasley.