On D+2 we were just off the south end of the island, in a Landing Ship, Tank.

At about 1700, we were told to report to our equipment.

We started our engines, the LST opened its bow doors, and the ramp dropped. We were at Red Beach. A Caterpillar bulldozer went first, to build a dirt ramp.

Once that was ready we moved out — trucks, more Cats, and then my Northwest 25 crane.

The noise was continuous. Wreckage was everywhere. It was getting dark when I got to shore, close to Mount Suribachi.

There was a 30-degree slope up from the beach; I barely made it to the top of that volcanic sand.

My partner Red and I were to share a foxhole. Trying to move that sand was like digging flour.

I took the first watch and let Red sleep. When it was his turn, he woke me up every time he heard land crabs.

Finally I gave him my bolo knife and told him that only after he had shot the carbine and stuck the enemy with the bolo could he wake me.

We were issued D rations, bars about two-and-a-half by five-and-a-half inches that looked like chocolate but were grainy, not sweet. Three bars was one day’s supply.

Navy guys on the ship had gotten into the canned goods we had stowed on the crane, but they hadn’t fooled with the five-gallon can of water we had hidden in the boom. We were thankful to have that, since we were allowed only two canteens of water a day.

On D+3 we woke at dawn but couldn’t leave our foxholes until we had clearance from security.

Finally we got up, relieved ourselves — no toilet — and saw men from our battalion. Cats went to clear the beaches. Dump trucks were hauling supplies. After we hung the crane with a clam bucket — the Marines needed a water point dug across the island for distributing fresh and desalinated water — Red and I split up.

I started for the beach in the crane.

A Northwest 25 was a big, slow thing on treads with a rotating cab and long boom; even with its big diesel engine it only did about two miles an hour. It was going to be a while before I could dig that water point.

All around me were Marines trying to get somewhere. Right in the middle of the road some of them had dug a hole and were setting up a 105mm howitzer that they pointed at the Japanese a hundred yards away on some rocks.

After they shot five rounds that killed everyone on the rocks they moved the gun and I filled in the hole and went down to the beach.

Far enough up from the sea to avoid the tides, I dug five holes, each 20 feet in diameter, down to the water table.

Other Seabees and Marines set up evaporators, pumps, and storage tanks for the water point.

I was told to go to the battalion’s new bivouac, below the old Japanese airfield nearest Suribachi.

I left my machine there at the strip.

At the bivouac two guys from my company and I remodeled a shell crater for our quarters. I stole a tarp to cover it. For sanitary facilities we had slit trenches we squatted over.

Around D+5, my company commander, Lt. Pond — I don’t think I ever knew his first name; we generally called him “Mister Pond” — told me my mother had died.

There was no way he would be able to get me home to bury her. We couldn’t even move wounded men off the island.

I wanted to send money for the funeral, but the paymaster was out on the ship. Lt. Pond loaned me $100 and took care of sending it home.

He was an outstanding officer. I didn’t mind calling him “Mister.”

I needed to work on the airfield, so the mechanics changed my rig over from a bucket to a shovel. I put in nine or 10 hours a day extending the original airstrip to make it big enough to accommodate B-29s.

Marines were fighting for the very piece of ground where we were trying to enlarge the strip.

We had to watch out for snipers and mortar fire and live ammunition and mines.

One evening after I finished my shift the first B-29 landed.

On D+6 the main body of the 62nd came ashore.

By D+7 the cooks and bakers had the cook tent erected and we got our first hot meal with baked bread.

Marines didn’t have chow lines, just K rations, so whenever they had a chance they got into the Seabee chow line.

We got water for showers from underground. It smelled like rotten eggs but it was hot enough. We made the pipes out of shell casings.

The showers were out in the open with no covering. Slit trenches got upgraded to four- and six-holers.

After working about 10 days I was sent to Airfield 2, a half-mile north, to help extend that strip.

I had to walk the crane with the shovel on it uphill past a B-29 in a gully with other abandoned equipment.

I noticed a bottle of sake and had gotten down to fetch it when a passing Marine said, “I wouldn’t handle that if I were you.”

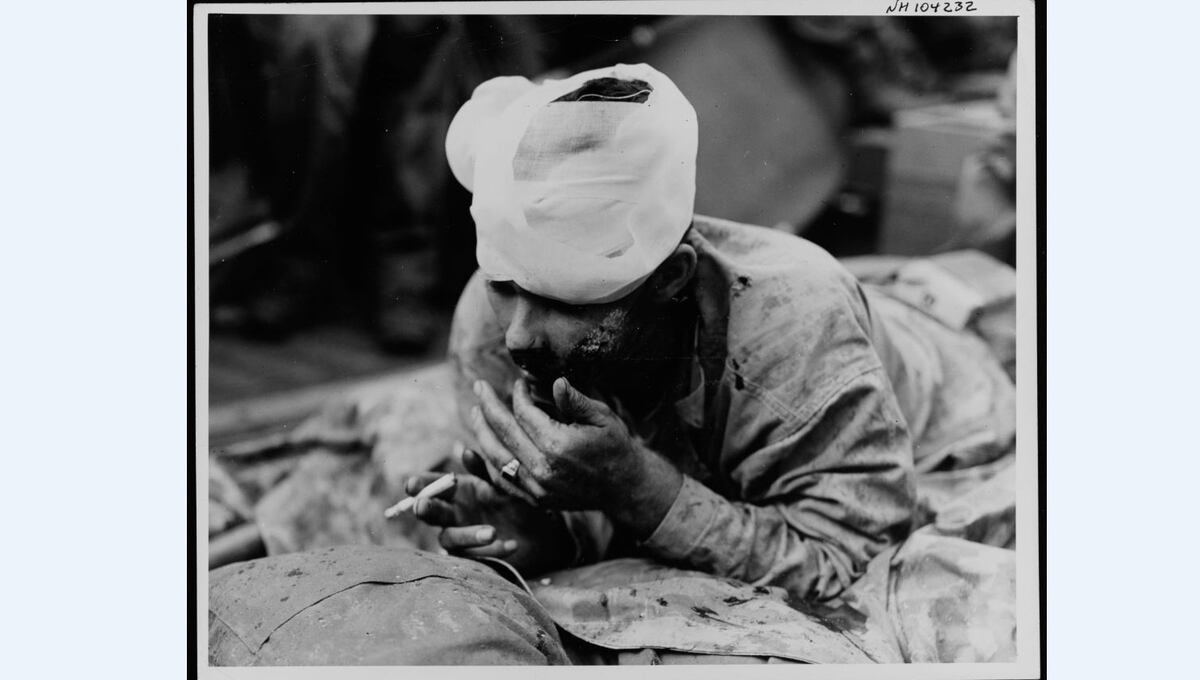

His face was bloody from hundreds of tiny holes made by a grenade. He explained that it was a booby trap and showed me the wires inside the bottle.

I gently put the bottle down.

The Marine was waiting to be treated nearby at an evacuation center that was also identifying the dead.

They had men going through pockets and checking dog tags and clothing and then stacking the bodies four or five high at an old Jap revetment. It was awful gruesome.

There was a 105mm howitzer behind our bivouac. The Japanese tried to knock it out with eight-inch guns.

The first shell hit about 20 feet from me and killed two of my buddies. The Japanese also were using giant mortar shells that tumbled end over end in the air, making a frightening screaming noise.

But they usually landed in the water. We figured they were launched from a trough, like Fourth of July skyrockets.

One day a Marine crawled up into my crane’s cab. He pointed to three guys about 100 yards away and said one was a lieutenant colonel who wanted to talk to me.

I hurried over. The colonel asked how far down I could dig.

“Twenty-six feet,” I told him.

“That ought to do it,” he said. “Can you move the rig?”

When I said yes the colonel told me I was temporarily relieved of my duties.

His sergeant drove me about three-quarters of a mile to a rise called Hill 382.

At the foot of the hill he showed me a flat area covered with dead Japanese, big mines and shell casings.

Then he drove me back to my machine.

It took an hour to fuel the crane and return to the work site. The sergeant was waiting there with 40 Marines who spread out on either side of me.

He had me move the crane forward to a cave, which the colonel told me to dig out. I dug all day.

We found supplies and living quarters, but no people.

That evening the Marines dug foxholes; they were on the fighting line. One drove me to my bivouac.

The next morning, when we realized we wouldn’t find anything more, the Marines burned out the cave with flamethrowers.

Then they sealed it.

I found out later we had been looking for the Japanese commander of the island.

Hill 382 became known as “Meat Grinder Hill.”

For 20 days I dug out caves.

At some we pulled out dead Japanese and rifles, pistols, and ammunition.

I sold souvenirs, mostly to Army Air Force personnel.

One day I found a bale of tube socks. From then on I never washed socks. Every morning I would put on a new pair.

I took a gun rack off a wrecked Jeep and mounted it on the nose of the crane cab, which seemed a better place to keep my gun than the floor of the rig.

The front windows of the cab were hinged so I could get hold of my weapon in a hurry.

Our battalion moved to the flat area by Meat Grinder Hill where all the dead Japanese had been.

We called it "Camp Cadaver."

Carpenters laid out six-man tents, mess and supply tents, and maintenance shops. They put in generators.

There was mortar and sniper fire, and Japanese bombers flew over dropping bombs, so we dug foxholes.

At night the Japanese would come out of caves to get food and water and try to infiltrate, so we had guards around the clock.

After the Japanese shot a replacement Seabee from our bivouac who had been nosing around a cave on Meat Grinder Hill, the company commander assigned me to make a trench about 4 feet across and 5 feet deep in front of the mouths of the caves so that anyone leaving them would have to cross the trench.

Once I had backed my rig out of the way, guards parked trucks about 50 feet from our tents with their front ends aimed at the trench, which they rigged with trip flares; if someone tripped the string, the flares would fly into the air and ignite and float down under a tiny parachute.

That night a flare went up and the guards turned on the trucks’ headlights.

They fired submachine guns, .30-caliber machine guns, and rifles and killed 13 Japanese.

The next day I was about to start digging at the same cave when I saw a Japanese man wearing only a loincloth.

I dove out of the front window of the cab and grabbed my gun from the rack but I had on such heavy gloves I couldn’t pull the trigger.

A Seabee lieutenant ran up with a .45 and we took the man prisoner.

That didn’t happen often on Iwo. I saw dead enemy soldiers tied to their antiaircraft guns.

When I went back to work, I hit a bonanza — a box about the size of a footlocker, full of 10-yen notes.

One of those went for a buck.

I borrowed a Jeep, loaded it with scrip, and drove to where the pilots and mechanics had their tents.

I came back with $150 cash, two bottles of champagne, and 13 eggs, plus souvenirs I could trade.

I had to give the Jeep back, plus a bottle of champagne for the use of it, but then the guy let me have a motorcycle with a sidecar.

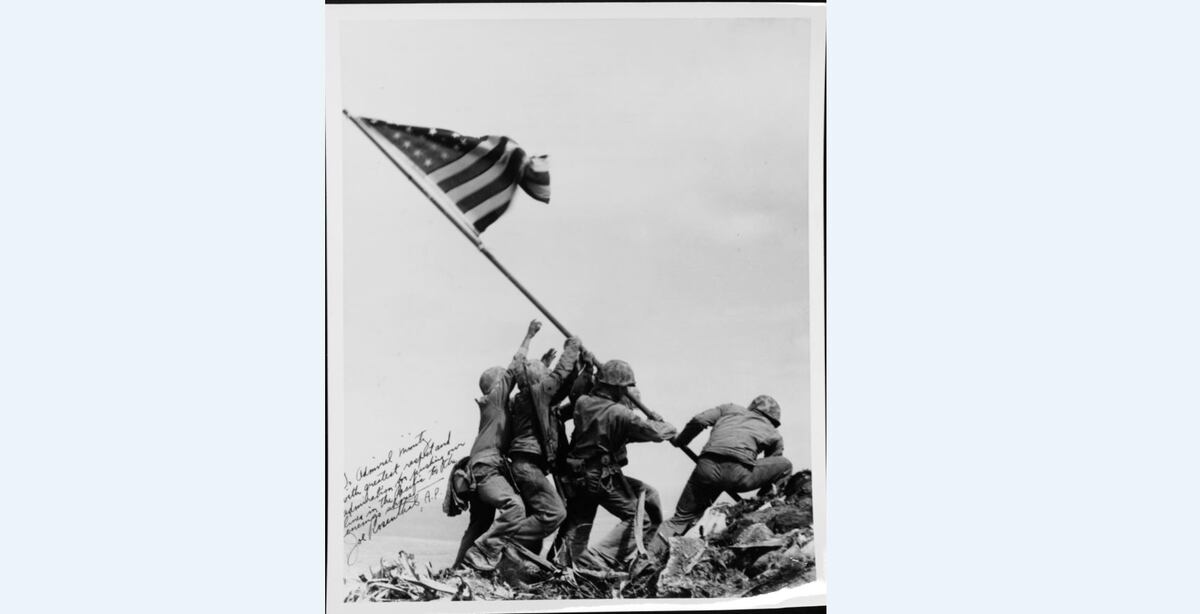

Off I went with a load of souvenirs. After I sold them I decided to go to Suribachi.

By then the 31st Seabees had built an oiled road to the top; it was so steep I had to go in low gear.

At the top I looked into the volcano and at lots of caves and the battleships and cruisers offshore.

I didn’t see the famous flag, whether because it had been taken down or I just wasn’t looking in the right place.

Coming down was as bad as going up, low gear all the way, but I returned the motorcycle in one piece.

Nobody else in my unit ever got up there.

When I got through digging caves, I went back to the northernmost airfield to excavate a drainage ditch alongside the runway.

Pilots were supposed to stay off the strip where I was digging and use the completed strip parallel to it.

A B-29 touched down on my strip anyway and was heading right for me when the pilot realized he wasn’t supposed to be there.

He turned hard, right into a hill, and wrecked the plane. A day or two later another B-29 came in the same way. His brakes were shot.

When he stopped, his plane’s nose was against my rig’s boom.

B-29s made me nervous. I would put an iron barrel by whatever hole I was digging so pilots could see I was working.

I had no sooner gotten back in my rig than a B-29 made a real wide turn. His outboard left prop hit the barrel.

The pilot was screaming. His left engine was wrecked, he had a load of firebombs, and he had to abort his flight.

There was often tension like that.

McClenagan, who commanded C Company and ran the asphalt crew, was a real hothead, very protective of the strips his men laid down.

When one of the Cat operators accidentally gouged a stretch of asphalt, McClenagan threatened him. The Cat skinner pulled his Ka-Bar knife and slit McClenagan’s shirt bottom to top.

The day after the slit shirt I had a run in of my own with McClenagan.

The Japanese had buried ammunition all over Iwo, and I had our battalion’s only backhoe, so I was often sent to dig out ammo.

At the edge of a strip that we had blacktopped and which B-29s were using, I scraped a few bucketfuls of dirt a couple of feet from the pavement.

Smoke came out.

Whoever had blacktopped the strip had laid asphalt right over an ammunition dump that was now on fire.

Fortunately it started raining. I was able to dig a trench that funneled water onto the ammunition and stopped the fire so I could keep digging.

At the same place we found some of those giant mortar shells. I was digging around the mortars so the demolition team could get at them when I accidentally cut into the strip as McClenagan was driving up.

“What the hell are you doing?” he yelled. “You’re wrecking my blacktop!”

I explained that I had to clear a path to buried Jap ammunition.

McClenagan was furious. He pulled his .45 and aimed it at me, cussing the whole time.

I swung my bucket so it was hanging over his head and told him if he shot me my foot would go off the brake and the bucket would chop him in two.

Right then Lt. Pond drove up.

“McClenagan, you son of a bitch, you’re bothering my men again!” he shouted.

He pulled his lieutenant’s bars off his collar and went right up to McClenagan’s face: “I’m going to beat the shit right out of you.”

McClenagan got out of there.

Lt. Pond took me to camp and told me to stay in my tent. I was concerned because I had threatened an officer.

A runner told me I was under arrest, but no charges were brought.

I never saw McClenagan again.

One day, three or four man-hauls — trucks with seats for troops — pulled up by the Army Air Force tents.

They had brought Red Cross workers who began setting up coffee and donuts.

I hadn’t seen coffee in a regular cup for some time so I got in line.

A man asked who I was. I told him I was a Seabee.

“Well, you can have a donut and a cup of coffee,” he said. “But this is for officers so don’t hang around.”

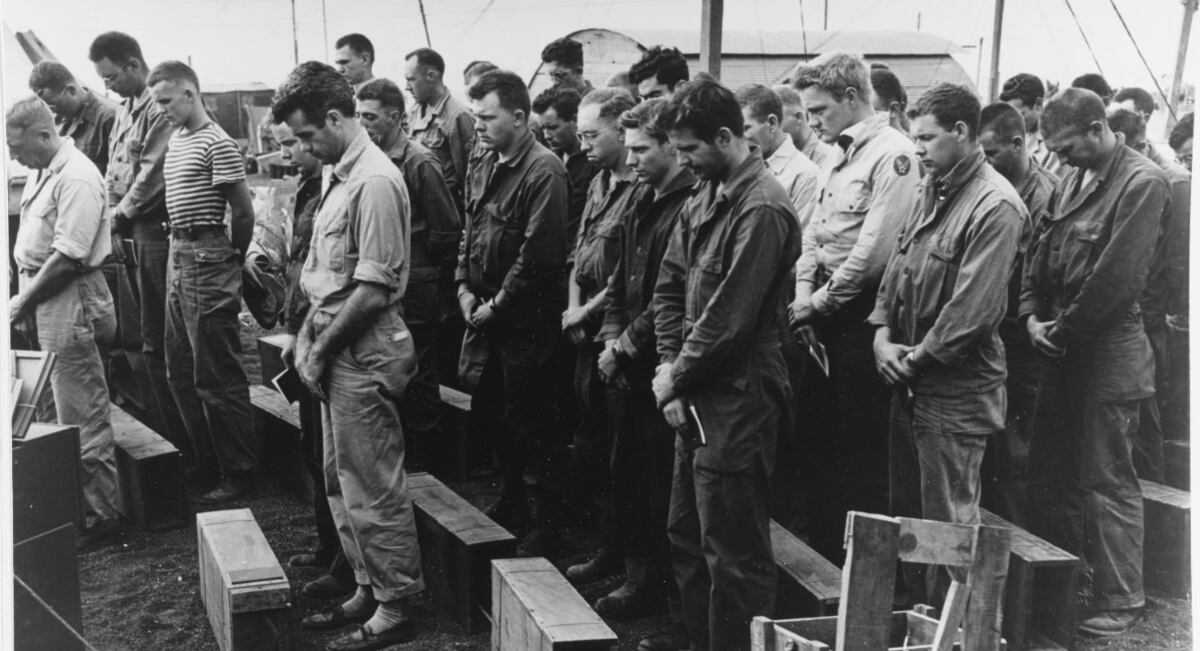

On March 16, Iwo was declared secure.

Two days later the 5th Marines reached the north end of the island.

I was on Airstrip 2, filling trucks, when the Marines marched by in formation.

Wherever a man was missing, they left a space.

Some companies had only four or five men in their usual marching positions, but with big gaps all around them.

They were dirty, unshaven, tired, and haggard, wearing torn clothing.

We stopped what we were doing and watched, silently mourning those missing men. It was heartbreaking to think that all those 18- and 19-year-olds were gone.

It took more than half an hour for the Marines to pass the airstrip. They stopped at the 5th Marine Division Cemetery for a short service before going to the beach to load onto ships.

The Army took over for the Marines, and Army engineer units began working alongside us Seabees.

That August, I was in my crane on Airstrip 2, where I had been ordered to dig a big hole for a special hydraulic platform, when a B-29 landed.

Military policemen surrounded the plane.

I figured something was up, so I got the battalion photographer. As soon as the guards saw him taking pictures they grabbed his camera and shooed us away.

Later I learned that a B-29 had been standing by on Iwo to carry the atomic bomb meant for Hiroshima in case the Enola Gay had to abort its mission.

This article was originally published in the December 2014 issue of World War II Magazine, a sister publication of Navy Times. To subscribe, click here.