A new study offers few definitive conclusions for why fewer women choose to stay in the Coast Guard compared to men, but it offers several reasons why they want to get out.

The report, released a few weeks ago by the non-profit RAND Corporation, was commissioned by the Coast Guard and is the first study in nearly 30 years to look at women in the service’s ranks.

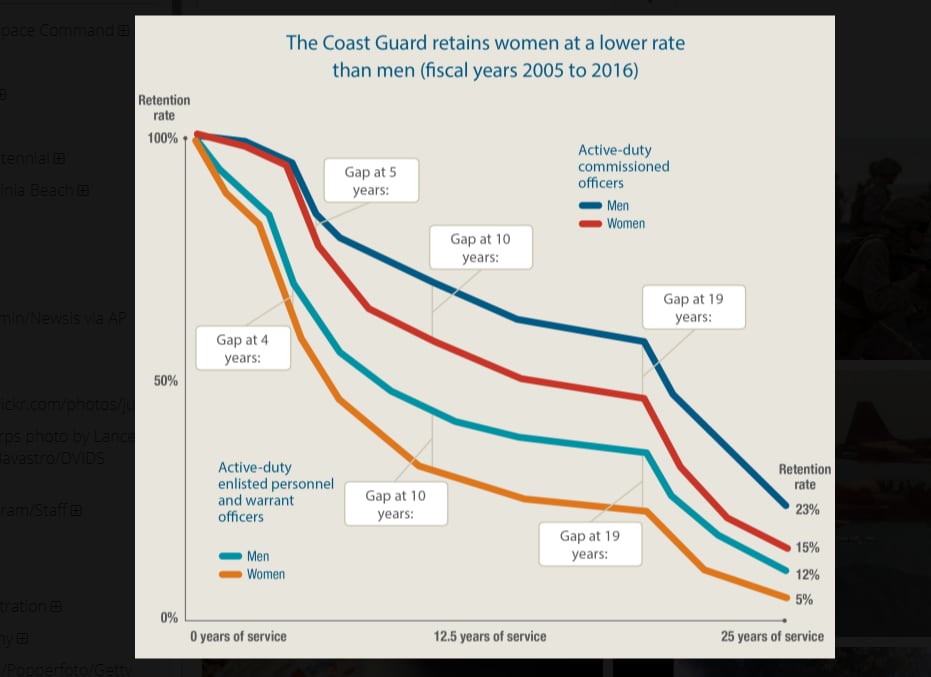

Fewer female enlisted or officer Coast Guard members make a career in the service or even stick around at the four-year or 10-year mark, according to the study.

Compared to their male counterparts, 12 percent fewer female Coasties will stay in the service after a decade in uniform.

About 23 percent of male officers will serve a 25-year career in the Coast Guard, while 15 percent of women officers will do the same.

On the enlisted side, just 5 percent of women will serve 25 years, while 12 percent of their male counterparts hit that point, according to the study.

The Coast Guard’s Office of Diversity and Inclusion commissioned the survey to ferret out root causes behind lower retention rates of women and to get recommendations on how to fix that.

It’s part of an effort started last year by the service to look at challenges affecting the workforce in general. A final plan and report are expected next year.

At his annual State of the Coast Guard address last month, Adm. Karl Schultz pointed to several changes already in the works, including revamping the regs that disqualify single-parent enlistments, loosening weight standards and easing tattoo restrictions, part of a larger effort to convince more women to say in the service.

“They’re small ripples that will lead to a groundswell of cultural change,” Schultz said. “Inclusion allows for development of the critical bonds that will put us on a course to mission success.”

Rand’s study cautions there are no “silver bullet” solutions to the retention woes.

Despite the achievements of women in the military, the services largely remain a boy’s club, and the 164 focus groups with 1,010 Coast Guard members interviewed for the study revealed women voicing concerns about problems shared with women in the other armed forces.

Issues raised included having to tolerate inappropriate comments uttered by male peers, who also exclude women from group activities.

“Some reported that, when a woman does interact with male peers, she can be subjected to rumors of engaging in a sexual relationship, with any stigma being placed on her, not him,” the study states.

Coast Guard women also raised sexual harassment and assault problems as reasons for lower retention rates.

“Some participants commented that units with only one or two women assigned and units in remote, isolated environments also tended to experience sexual harassment or assault more often than other units,” the study states.

RELATED

The focus groups noted advancement challenges in the service, and how berthing restrictions for women on vessels can limit career opportunities, according to the study.

“Some women also said that they are routinely assigned collateral duties that are stereotypically female activities and that are less likely to support career development,” the study notes.

Female personnel reported that male leaders are “reluctant to mentor women” in their units, and that women-specific policies are interpreted or implemented inconsistently.

“Female participants expressed the belief that men and women were treated differently; and that men often did not trust their opinions or value the quality of their work, particularly in male-dominate ratings or specialties,” according to the study.

When it comes to having kids, Coast Guard women reported a “lack of breastfeeding support” at times, compounded by few facilities for pumping breast milk and commanders who were reluctant to allow proper breaks for doing it.

Pregnancy affects a female Coast Guard member’s ability to acquire qualifications and experiences that will advance careers, and some respondents told researchers that male colleagues get “frustrated at having to fill in when women are on parental leave.”

“Women described being accused of getting pregnant just to get out of duties or having to go underway,” the study states.

Women also reported retention being affected by “perceived unfairness of weight standards” that don’t consider body types and changes after childbirth.

“They noted as particularly problematic the use of the taping process as a measure of body fat to enforce weight standards,” the report states. “Furthermore, participants felt that standards were not aligned to job ability.”

Some focus groups were male, and both men and women members noted workload, assignment processes and opportunities in the civilian world as factors affecting retention.

Coast Guard women also reported feeling like they’d have to choose between the service and their families at some point in their careers.

Those with civilian spouses cited concerns about frequent moves and other issues regarding life in the Coast Guard.

While 7 percent of Coast Guard men are in dual-military marriages, about 52 percent of married Coast Guard women wed other members of the armed forces, the study found.

RELATED

Personnel data showed a plurality of enlisted women working in service or support ratings, fields with the fewest enlisted men.

Men were more likely to be afloat than women, and the afloat sector sees higher retention rates than ashore commands for both men and women, according to the study.

The study recommends the Coast Guard look into reforming several areas to better retain women.

Leaders should explore options for augmenting units when a female member goes on parental leave and consider ensuring that evaluation periods for promotions aren’t adversely affected by a woman having a baby, the study states.

The service needs to “explore creative solutions” to berthing shortages for women at sea while ensuring female-specific policies are understood and disseminated by leaders.

Among other prescriptions, the report recommends the Coast Guard better track workforce data for certain gender-related categories so that future assessments can be based on strong sets of data.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.