In the spring of 1945, at age 17, I volunteered for the U.S. Navy.

Nazi Germany had surrendered, but World War II was still raging in the Pacific as the Americans closed in on Japan’s home islands. Kamikaze planes were diving into ships, killing sailors by the dozens.

Most of my thoughts and feelings were with those embattled men 5,000 miles away. When I enlisted, I had no idea I was about to participate in a historic experience that in some ways would prove more momentous than the final struggle against the Axis powers.

Orders from the Navy directed me to report to New York’s Pennsylvania Station, where I boarded a train with other new recruits that took us upstate to boot camp at the Sampson Naval Training Station. Soon after we arrived, we were divided into companies and marched to our barracks, as Seneca Lake gleamed in the distance.

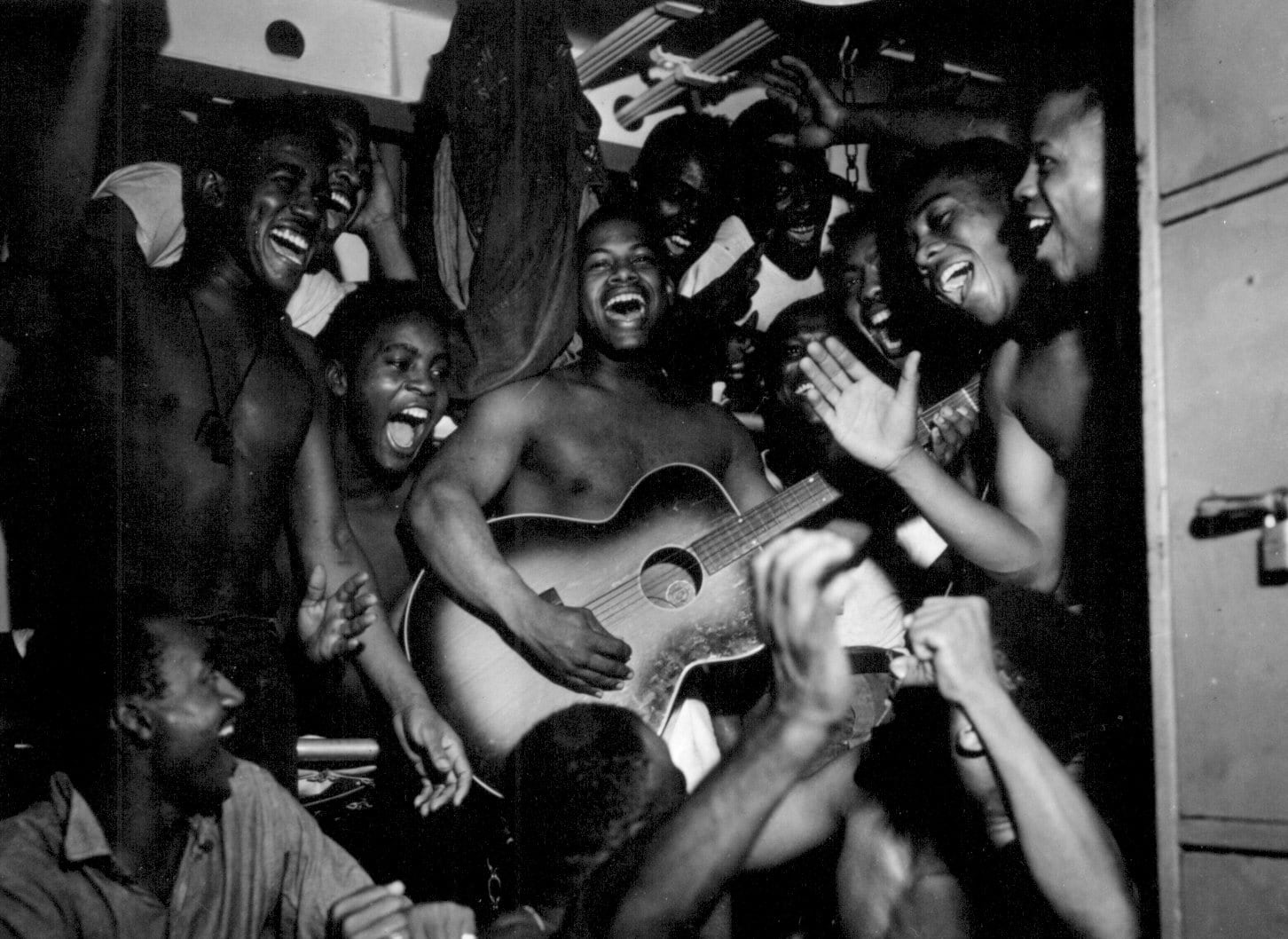

A chief boatswain’s mate led me and some 150 other would-be swabbies to our barracks and checked off our names as we hefted seabags and settled into the spartan interior — where everyone got a shock. We were an integrated company — a third black, two-thirds white.

Without announcing it, the Navy was launching a program to upend the prevailing race-relations formula in the United States — separate but (supposedly) equal.

As I sat down on my lower bunk, I saw that I had black sailors sleeping on my right and left and in the bunk above me. We all gazed at each other, trying to figure out what to say or do next. I asked myself what my politician father would do — and held out my hand.

“I’m Tom Fleming from Jersey City. Where are you guys from?”

We shook hands and introduced ourselves. Around me other recruits were doing the same thing.

So began our historic experiment.

As a Catholic, I had been taught to believe in racial equality, even though the Catholic schools in which I was educated had very few blacks. Our teachers said that this was because of our differing religious heritages: Almost all blacks were Protestants and went to public schools.

In Jersey City blacks lived in a broad swath of housing in the center of the city. They worked in factories alongside whites. Blacks voted in all the elections. My father had 5,000 black voters in his ward. He did favors for them without the slightest hesitation.

That was how the Democratic Party worked.

But relations between black and white teenagers were not friendly. One of my more vivid memories was the night the sound of thudding feet in the street outside my home drew me to a window. I saw about 20 black teens running as fast as possible down the center of the street. After them came at least 40 white teens, members of a gang called the Rangers.

I had no illusions about race relations. But I knew our country would be better if we could improve them. Yet there in boot camp on Seneca Lake, no one preached a sermon to us about the importance of our integrated group.

In retrospect, I see that this omission was clever rather than careless: It was more effective to imply there was nothing strange or unusual about integrating the Navy. But we understood how significant it was. That may explain why we all tried to get along with each other.

Over the next eight weeks, I did not hear — or hear about — a single hostile or acrimonious exchange.

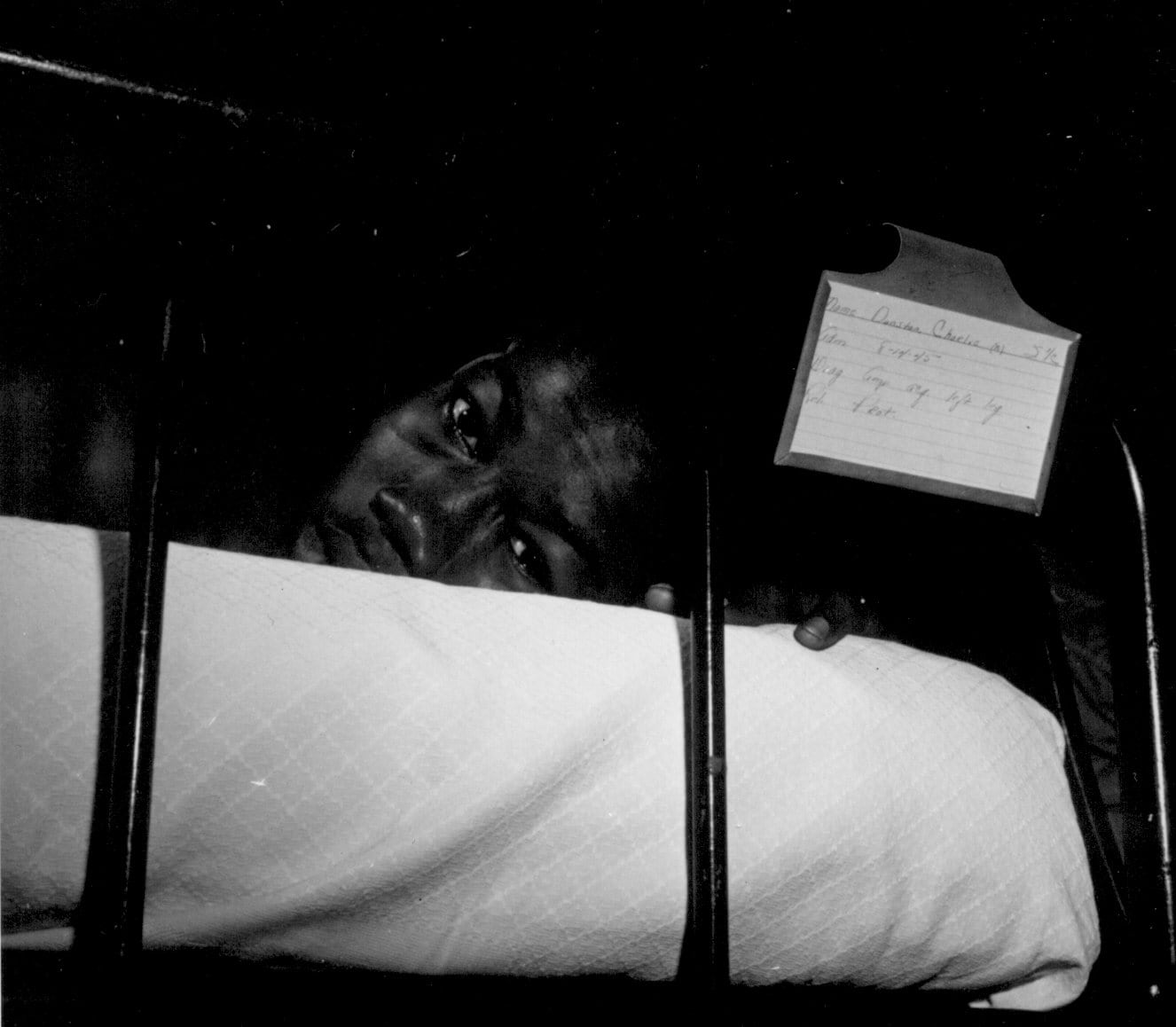

I became particularly friendly with Jefferson Jackson, who, like the other two black men in bunks near mine, was from Detroit. Tall and thin, Jeff was a little older than the rest of us. He told me that his father, an undertaker, had kept him out of the draft for two years by pleading that his help was needed in the funeral home.

But Jeff disliked people calling him a draft dodger, and he eventually persuaded his father to let him volunteer for the Navy.

Jeff was fascinated when I told him about the prejudice my Irish grandfather had encountered when he came to America in the 1880s — not many people wanted to give jobs to Irish immigrants at that time.

Jeff described a similar problem his grandfather had encountered in Atlanta, Georgia, after the Civil War freed him and his family from slavery. Then, when the family moved north to escape Southern prejudice, they found that even in the North, a lot of jobs were closed to blacks or were segregated by position, with blacks mostly in the lower paid ranks. He added somewhat wryly that there was still a lot of prejudice around — more subtle and sometimes invisible but still there, barring blacks from good jobs and promotions.

Meanwhile, boot camp went on. Among our tougher assignments was learning how to put out a fire on the lower decks of a warship. Replicas of ship compartments in our training area were flooded with knee-high water, then oil was spread on the water and set afire.

I still remember the day we had to wade into one of those infernos with a huge hose. Jeff Jackson was at the nozzle, I was behind him, and four other sailors were behind me, two white, two black. The men in charge made it as realistic as possible.

When we had extinguished the blaze deep in the compartment, they set another fire between us and the entering hatch. That second blaze was frequently a cause of panic among trainees. But we met the challenge so well, wheeling quickly and covering the flames with a layer of smothering foam, that our trainers shouted their congratulations.

All of our training assignments went well. We were a team. Off duty after dinner, we played softball on an improvised field near the barracks.

One burly black sailor, whom everyone called “Babe,” was a slugger of the first order. He repeatedly belted the ball out of sight. We all wanted him on our team.

Soon our boot camp days were over. After a brief visit home, I joined about a hundred other sailors on a train headed to Portland, Oregon, where I became a fire-control man aboard the light cruiser Topeka.

I noticed that none of our black barracks mates accompanied us. But there were hundreds of ships in the wartime Navy, and I assumed they had gone elsewhere.

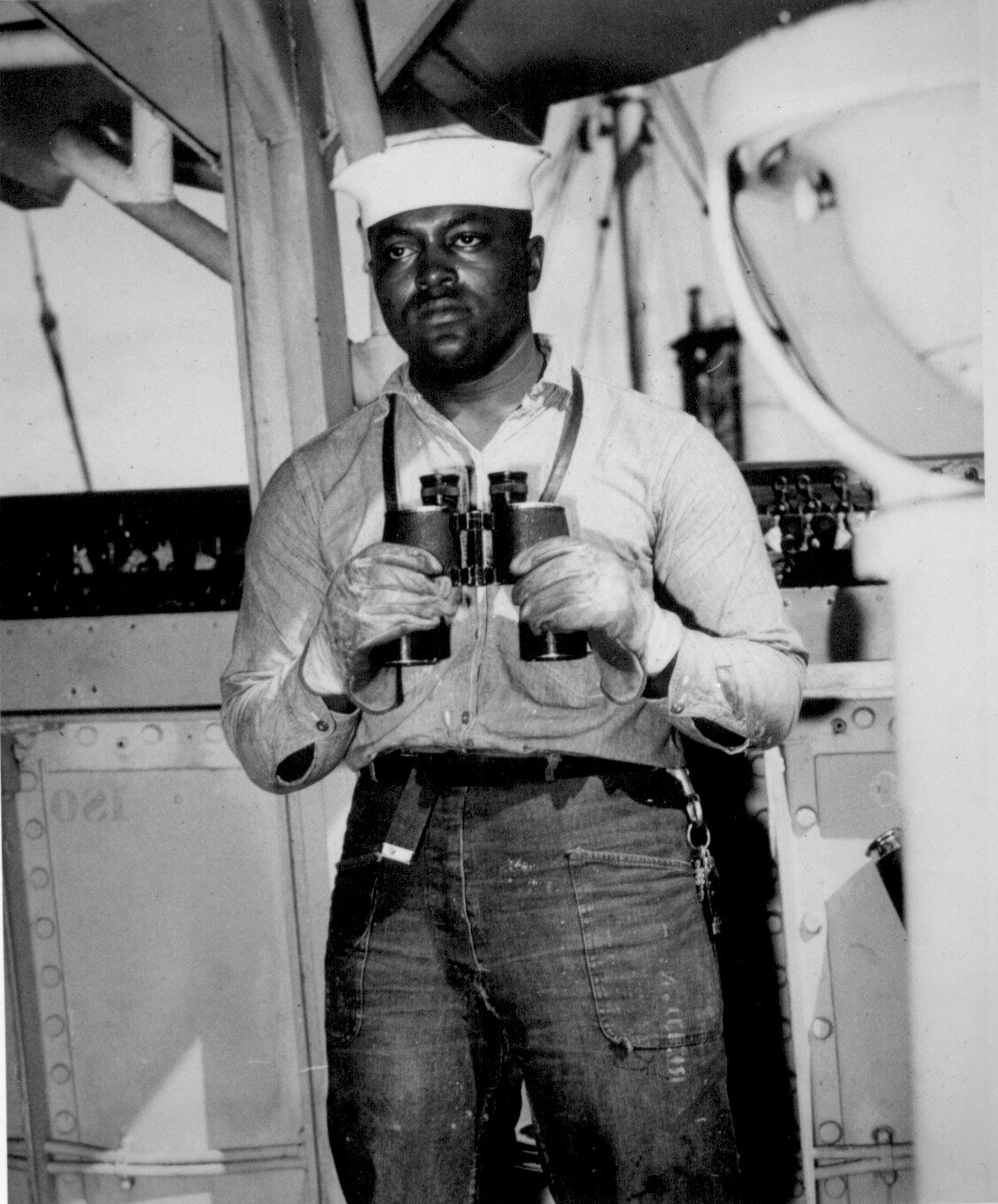

Then I realized there were no black sailors at all aboard the Topeka, except for the 40 or so stewards who served as waiters in the officers’ mess. When I asked one of the officers in command of the fire control division about this, he told me that most black men in the Navy were assigned to work at shore bases.

No one in Washington, D.C., it seemed, thought whites and blacks could get along in the close quarters of a ship.

The Topeka sailed to Long Beach, California, where it joined the U.S. 7th Fleet. By that time the atomic bomb had ended the war with Japan, and the Seventh Fleet had orders to become part of the American occupying force.

About a week before we sailed, news raced through the Topeka about an extraordinary sight in the harbor.

“There’s a landing craft heading for the USS Alabama with 50 black sailors in it,” one excited petty officer told me.

We watched as the stubby boat pulled alongside the huge battleship, and the black seamen ascended a ladder to the deck. For the next hour, the Topeka vibrated with speculation about the possibility that the Navy was going to integrate ships at sea as well as bases on land.

Then, new scuttlebutt rang through the ship that the black sailors were going back to land. Once more, we rushed to the Topeka’s main deck, where we saw the same landing craft plowing steadily away from the Alabama and back toward the Long Beach docks. It was full of the black sailors. The tilt of their white hats seemed downward, as if a blow had bent their heads.

The admiral in command of the Alabama, it turned out, was from Alabama, and when he saw the black sailors coming up the ladder, he had roared that no black seamen were coming aboard his battleship unless they were mess stewards.

I wondered if my friend Jeff Jackson had been among those black men.

I felt ashamed for my country.

There would be no black seamen for a long time to come. Even after President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981 in 1948, integrating all branches of the U.S. military, every ship of the line remained white.

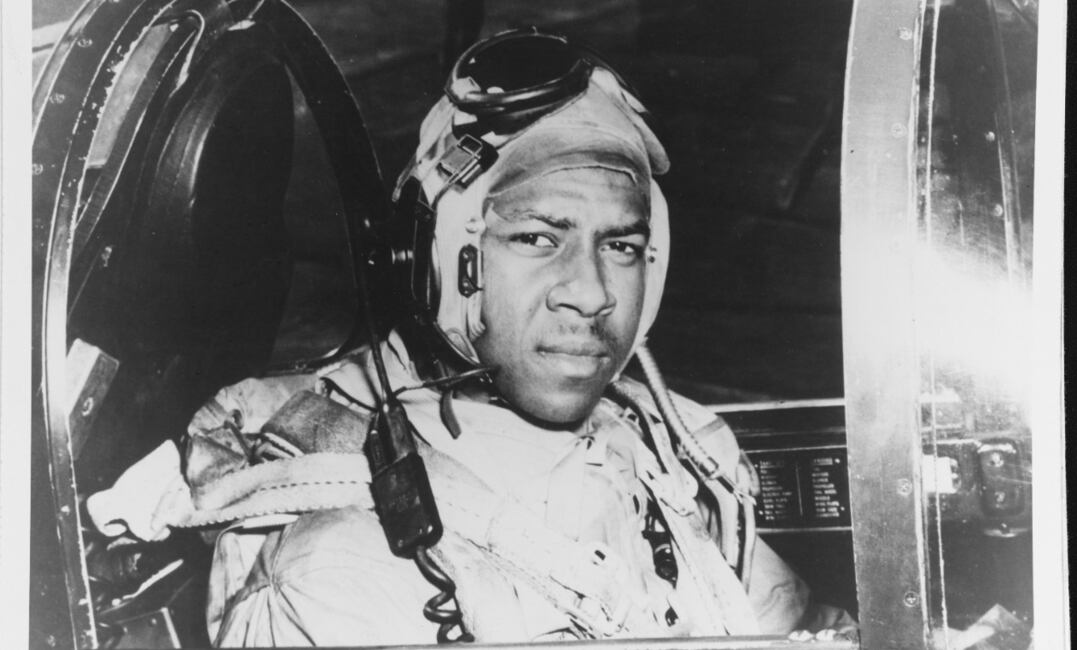

But the navy had heard Truman’s order loud and clear, and it accelerated the integration process in certain training programs, particularly the one for aviation machinists.

Still, a 1949 congressional committee report revealed that the admirals had work to do. Of the meager 17,000 blacks in the navy, only 19 were officers and two of those were nurses, while a total of 10,000 were in racially segregated assignments.

The Marine Corps had an even more dismal record — a total of 2,190 enlisted black men and no black officers. Instead of issuing denunciations, various congressmen chose to praise the “progress” made and to express confidence that integration would gradually become a reality.

Eventually, that happened, with the Navy leading the way. It steadily increased the number of black sailors aboard its ships, and black officers were added through a special NROTC program.

The other services were slower and more reluctant to follow suit. Gen. Omar Bradley, the Army Chief of Staff in 1948–1949, declared that soldiers could not be expected to integrate as long as segregation was the rule in civilian society.

But the need for manpower in the Korean War overcame such objections and changed a lot of generals’ minds, especially when they saw that integrated companies fought as well or better than the rest of the men in the front lines.

The Supreme Court’s 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision integrating the nation’s schools and the 1964 Civil Rights Act banning segregation in other parts of American society also became motivating forces for all the military services.

In 2008, America’s soldiers, sailors, and airmen celebrated the 60th anniversary of President Truman’s Executive Order 9981 by proudly declaring themselves the best-integrated organization in the nation.

Seventeen percent of the active duty force was black (two years later, in the 2010 census, blacks accounted for 13.6 of the total U.S. population).

While just under 6 percent of the admirals and generals were black in 2008, talented young black officers were emerging from the service academies in a steady stream, and black women were being accepted in the ranks as readily as men.

I have been a pleased observer of this rarely discussed story of race in the military. When I wrote Time and Tide, a novel about the navy in the World War II Pacific, one of my characters was a black water tender first class named Amos Cartwright.

Thanks to his mechanical abilities, he had managed to talk his way out of being a mess steward, and he reigned as the virtual ruler of the engine room aboard the fictional Jefferson City.

In one of the sea battles off Guadalcanal, Cartwight dies heroically, saving everyone else in the engine room from agonizing death after a steam valve ruptures.

Amos was my tribute to those days in 1945, when I discussed race and ethnic prejudice with my friend Jeff Jackson in our barracks at Sampson Naval Training Station.

Today there are thousands of Amos Cartwrights in our fleet, all proud sharers of the navy word for brother: shipmate.

RELATED

Thomas Fleming’s latest book is The Great Divide: The Conflict between Washington and Jefferson that Defined a Nation. This piece originally appeared the July 2, 2015 edition of MHQ Magazine, a sister publication of Navy Times.