Sailors unfamiliar with aircraft carrier life might assume that the pilots launching and landing on a flight deck face all the danger.

But a crew helping to launch, recover, move and park those jets confronts many perils, including being knocked down by the force of jet exhaust.

Fractions of a second can determine life or death on a flight line, and that brutal reality became the focus of a Navy probe into a mishap that severely injured a chief in late 2017.

On the evening of Nov. 3, 2017, the chief aviation boatswain’s mate (handling) was knocked off balance by one jet’s exhaust as the aircraft carrier Carl Vinson conducted launch and recovery training in the Pacific Ocean, southwest of San Diego, according to the report.

The chief tried to catch himself, fell and a second 31,500-pound F/A-18E Super Hornet ran over his legs.

The injured chief’s name was redacted in the command investigation copy provided to Navy Times in response to a Freedom of Information Act request.

Citing privacy and medical regulations, Naval Air Forces officials declined to say whether he remained in the service or was medically discharged.

The aircraft handling officer in flight deck control told the investigator of the mishap that sailors are blown off balance on carrier decks all the time.

“(The officer) indicated that it happened daily in his 26 years of experience,” the investigator wrote.

“There were only two ways to recover from losing your balance because of jet blast: either continue to run in the direction you were blown to regain your balance or get to the deck and grab a padeye,” the officer told the investigator.

A padeye is a metal loop attached to the deck that’s used to secure ropes, chains or cables.

“During qualification and familiarization, people are warned of the dangers of jet exhaust and educated on recovery procedures but that experience is only gained by being on the flight deck," the lieutenant commander told the investigator.

Given “this scenario, no one could have gotten out of this situation,” the officer added.

Naval Air Forces doesn’t track how many sailors get knocked down by jet exhaust, but spokesman Lt. Travis Callaghan acknowledged the incidents happen daily and that in most cases, “the severity is very low and require no medical attention.”

“Safety is Naval Aviation’s top priority and although the flight deck can be a high-intensity environment, our flight deck teams are the best trained in the world and will always endeavor to minimize risk,” he wrote in an email.

The chief was fully qualified for flight deck operations and his superiors did not discipline anyone involved in the mishap.

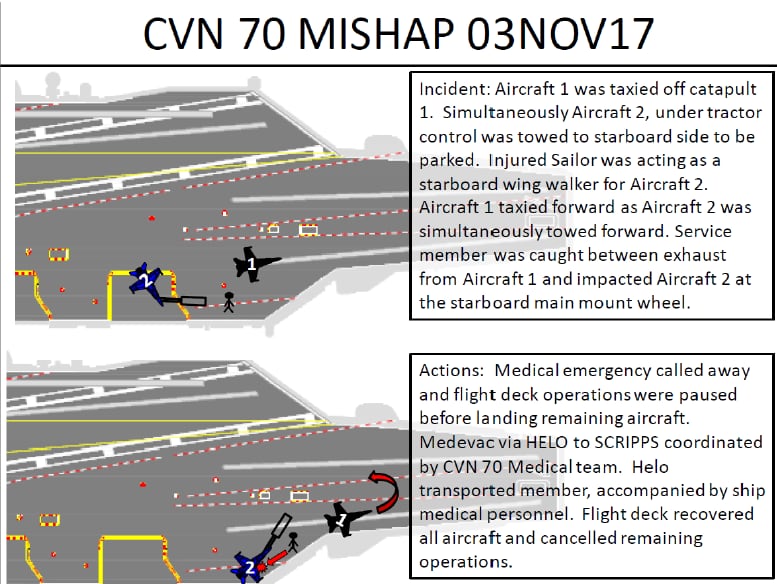

At 6:22 p.m. that day, the first jet was directed to taxi off the catapult after its launch was suspended because of a glitch in an exterior light on the aircraft, “a standard yet infrequent occurrence,” the report states.

As that first aircraft taxied forward on the ship’s right side, a crew was towing a second jet behind it, and the chief was acting as the starboard wing walker.

When the first Super Hornet began to turn, the jet’s exhaust blew the chief back, according to the report.

He stumbled, slammed into the second strike fighter, fell and his legs were run over.

A crew member who watched the chief topple blew a whistle to stop all movement on the deck.

An ensign and a chief ran up to the stricken man “and assessed him as having severe injuries to both his legs with visible blood and the possibility of severed legs,” the report states.

He was initially unconscious, but shipmates rubbed his sternum until he awakened and moved him to the flight deck battle dressing station.

“I don’t know what happened,” the chief said. “I can’t feel my legs.”

Another chief aviation boatswain’s mate (handling) told the investigator he thought the injured man’s legs were already severed but had been contained within his flight deck pants.

As he was moved, the injured man “expressed remorse for allowing this to happen and that he was sorry that the incident occurred and that he did not want his mother to find out about the incident from anyone but his sisters,” the report states.

His “blood and tissue” were left on the flight decks, and a medical captain assessed the chief to have suffered severe “de-gloving” on both legs.

De-gloving occurs when skin is ripped from the tissue beneath it, like taking off a glove. In his right leg, the shin bones had shattered and his calf muscle detached, among other injuries.

The captain suspected “that major and probably multiple surgeries would be required if there was any chance to save (the chief’s) right leg from amputation,” the report states.

He was soon flown off the carrier and to Scripps Memorial Hospital in San Diego.

The report does not indicate what happened to the chief after that but the carrier’s medical team instituted several reforms in the wake of the mishap.

For example, a hospitalman third class told investigators that the supplies in the battle dressing station’s mass casualty kit “were barely enough” for one patient and recommended they stock more bandaging material.

RELATED

The unnamed accident investigator concluded that the mishap was caused by several sailors on the second jet’s tow team losing situational awareness, and that the lieutenant commander in the first jet’s cockpit used “a rapid, yet within normal limits, power application” as he drew more fuel to move off the catapult.

Just three seconds elapsed between the chief getting knocked off balance by the jet’s exhaust and getting run over, and it would have been hard to prevent it from happening once he lost his balance, according to the report.

If the movement of the jets had been separated by even 10 seconds, the dangerous conditions that led to the chief’s injuries would not have existed, the investigating officer determined. But it could’ve been much worse.

“This accident was inches away from being fatal,” the report indicated.

The report recommended that flight and hangar deck manuals be updated so pilots know to use minimal engine speeds while departing a catapult and during similar scenarios. It also urged leaders to reinforce what flight deck crews should do if they’re knocked off balance in similar situations, plus other prescriptions.

In an early 2018 endorsement of the investigator’s findings, the commanding officer of the Carl Vinson wrote that the chief had lost situational awareness, but the CO didn’t blame the chief for what happened.

The CO’s name is redacted in the copy provided to Navy Times, but public records show that then-Capt. Doug “V8” Verissimo skippered he carrier when the report landed on his desk.

“Flight deck operations on an aircraft carrier are an unforgiving and dangerous business,” Verissimo wrote. “It took a confluence of conditions to cause this mishap, of which the momentary loss of situational awareness was only one predicate condition.”

While neither the first jet’s catapult departure nor the second fighter’s movements violated normal parameters, the unique situation “required extra vigilance,” he wrote.

Verissimo praised his crew for how they responded.

“It was the immediate, flawless, and professional response of the flight deck personnel and medical teams who prevented further injury or death,” he wrote.

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.