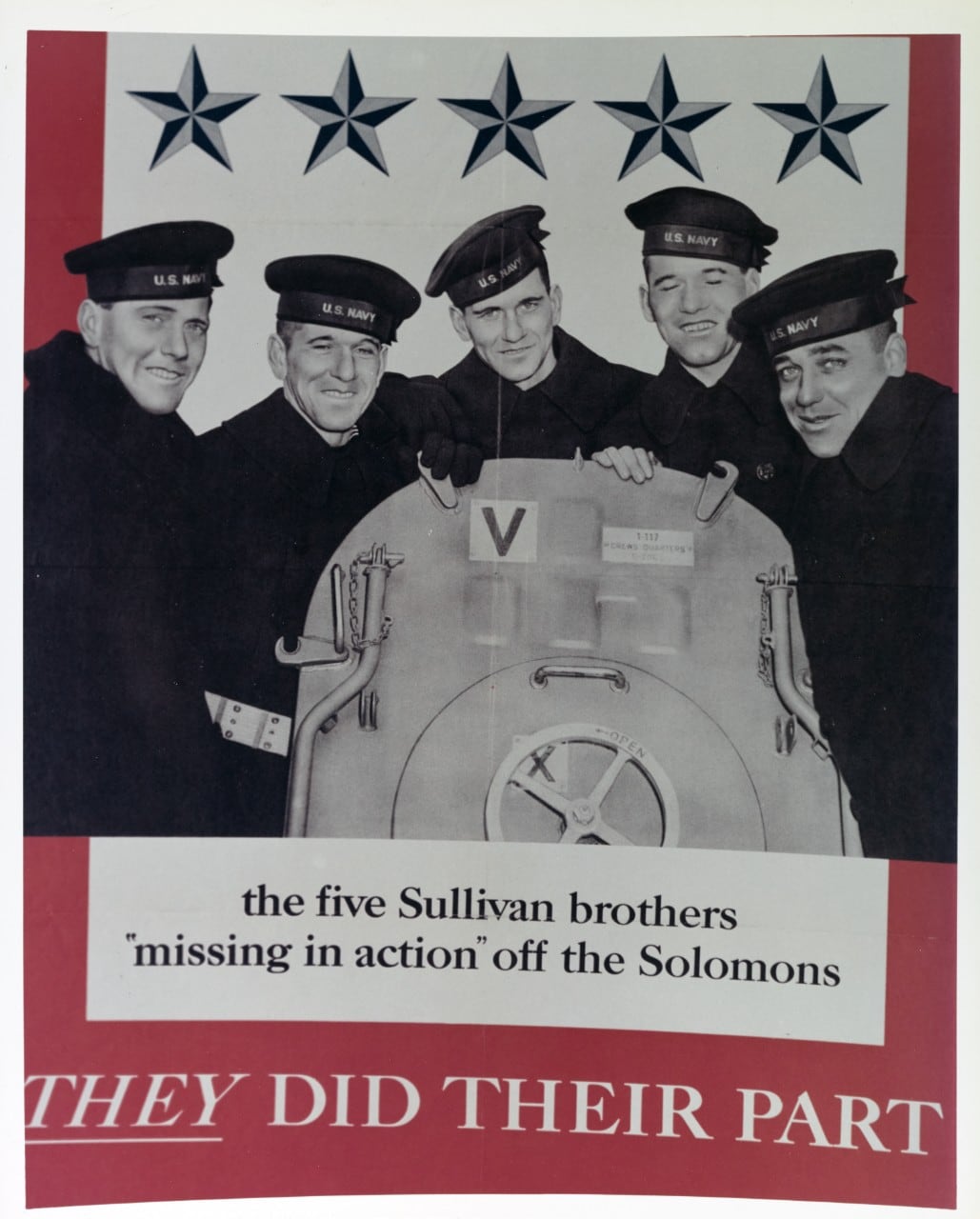

NAVAL STATION MAYPORT — The five Sullivan brothers of Waterloo, Iowa, died together at the Battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. Six family members were among those who gathered aboard the guided-missile destroyer The Sullivans, based at Naval Station Mayport in Florida, to honor their story.

Jim Sullivan, 78, wasn’t even two years old when his father, Albert, was killed during the Battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. He was of course too young to remember him, but oh he’s heard some stories.

"I want to choose my words carefully," he said, before deciding on a description.

"Typical Irish," he said. "Loved to raise hell and have a good time."

In death though, Albert Sullivan — along with his older brothers George, Francis, Joseph and Madison — became rallying points for a nation at war, symbols of sacrifice and a fighting spirit.

A movie was even made about them, with an appropriate title: “The Fighting Sullivans.”

The Sullivan brothers came from a blue-collar Irish Catholic family in Waterloo, Iowa. They joined the Navy after Pearl Harbor with the insistence that they would serve together.

They did, and all five brothers died when a Japanese torpedo struck their ship, the light cruiser Juneau, on Nov. 13, 1942.

In all, 687 sailors died in the attack.

Albert was the only brother who was married and had a child. On Sept. 27, six of his descendants came to Mayport Naval Station to visit the Mayport-based destroyer named after the brothers, USS The Sullivans.

It was part of a Jacksonville reunion for crew and family from the two ships that have borne that name.

Jim Sullivan is a Navy vet — it felt like his calling, he said — and retired licensed electrician who lives in Waterloo, his father's hometown.

He hasn’t traveled much in the last 25 years, and admitted he’s not much for the attention that comes with his connection to the story.

It took a visit to Iowa by the ship's captain and some crew members to persuade him to finally revisit The Sullivans, said his daughter, Kelly Sullivan Loughren, whose eyes sprung tears when she talked about her dad making the trip.

She also teared up while saying how she always tears up when she walks up the ramp to the ship and sees its symbol, a big green shamrock, and its motto: "We Stick Together."

Sullivan Loughren has become the point person for the Sullivan brothers’ legacy, saying it’s important to keep the story of their sacrifice alive — while noting the sacrifices made by all others who serve.

She pointed at the former crew members making their way up the ramp for a visit, and at the current crew that was gathered around her on deck.

"What we have here is 75 years of Navy service," she said. "The past, the present, and of course the future."

She's 48, a third-grade teacher who also lives in Waterloo. She is the ship's sponsor and christened it in 1997 at a shipyard in Maine.

According to an Association Press report at the time, she smashed a bottle of champagne against its side after saying, “May the luck of the Irish always be with you and your crew.”

RELATED

The original ship with that name was commissioned in 1943, and is now a memorial in Buffalo, New York.

The Sullivan brothers’ mother, Alleta, was its sponsor.

Try to imagine the grief that came with five sons dying at the same time.

Alleta and her husband Thomas heard no word of their fate for two months, leading her to write a letter in January 1943 to the Bureau of Naval Personnel.

"Dear Sirs," she wrote. "I am writing you in regards to a rumor going around that my five sons were killed in action in November. A mother from here came and told me she got a letter from her son and heard my five sons were killed. It is all over town now, and I am so worried ... I hated to bother you, but it has worried me so that I wanted to know if it was true. So please tell me. It was hard to give five sons all at once to the Navy, but I am proud of my boys that they can serve and help protect their country ..."

President Roosevelt wrote them back personally, noting that with her "gallant sons" missing in action, "I realize full well there is little I can say to assuage your grief."

The Sullivans reacted to their sons' deaths by going on a year-long war-bond drive across the country. They met countless service members, the president and some celebrities. Journalists told of their sacrifice again and again. The movie, made in 1944, spread their story even wider.

That kept his grandparents busy, Jim Sullivan figures, and perhaps kept a little of their grief at bay. "As the year went on and they weren't so busy, I think it bothered them, a lot," he said.

Sullivan Loughren said she thinks often of Thomas and Alleta crisscrossing the country, telling their story, trying to raise money to keep fighting.

"They did it for the right reasons. They wanted to help the war effort," she said. "And I know that's why the Sullivans are talked about today. My great-grandmother always said, 'My boys did not die in vain.' I think about that a lot when I walk the deck of this amazing ship: My grandfather and his brothers did not die in vain."

After the war, the Sullivans' parents, who also had a daughter named Genevieve, were not forgotten either, she said.

"They had sailors show up at their door. Seriously. They'd come back from the South Pacific and they'd knock on the door. They'd say, 'I know you don't know me, but I was in the South Pacific and I just wanted to give you my sympathies.' My grandma was a great cook, so she'd invite them to come in and eat. One guy stayed for six months. I'm not kidding."

RELATED

For the visit to the ship, Sullivan Loughren wore a blue jumpsuit bearing her name, Kelly, and brought her daughter Kelcie, 22, with her.

Her brother John Sullivan, 51, who lives in the Kansas City area, came with his daughters Madeline, 15, and Josephine, 12, whose names echo that of two of brothers, Madison and Joseph.

At home, he has the last letter his grandfather Albert sent home to Iowa, asking after family, assuring them that he and his brothers are doing OK, that they were safe. He said he reads it often.

The family and former and present crew members gathered on the mess deck for brunch, including a big cake decorated with a green shamrock made from icing.

After a couple of brief speeches, Cmdr. Pat Eliason, the ship's commanding officer, motioned to a visiting rear admiral, Roy Kitchener, and several crew members.

"Bring it in," he said, "bring it in."

They put their hands into the center of the circle and, joined by others in the crowded room, chanted the ship's motto:

“We Stick Together! We Stick Together! We Stick Together!”