The woods were infested with German soldiers, and the men knew it.

On the day before, their sister unit, the 30th Infantry Regiment, 3rd Infantry Division, had entered the Alsatian forest known as the Bois de Riedwihr and — having gone too far too fast, outrunning their artillery supports — been blown to pieces. The remnants of the 30th took refuge beyond the Ill River, in the direction of Holtzwihr, and awaited reinforcements.

That was why, on Jan. 24, 1945, the men of Company B, 15th Infantry Regiment, took up the approach march.

As Company B entered the woods, they encountered extremely heavy resistance in the form of sniper nests, artillery bursts fused for treetop detonation, mines, booby traps, mortars, and machine guns sited for cross fire. The company had to fight their way tree to tree, and by the end of the day they had little ammunition left.

When the company commander was seriously wounded by a mortar round, a fresh-faced second lieutenant, who looked more like one of Norman Rockwell’s newspaper boys than someone you’d trust your life to, was ordered to take command and resume the advance at first light.

The life of a second lieutenant in command of an infantry company during World War II was usually very short.

The chances of surviving to become a first lieutenant were slim; of surviving the war, slimmer still; and of emerging physically unhurt, almost nil.

In one 50-day period as this particular division fought its way through the hills of Italy, line units reported a 152 percent loss in second lieutenants.

The greatest likelihood of casualty occurred during a combat infantryman’s first 10 days in battle, but that of course did not mean that if he kept whole bones for 10 days he would not be or wounded on the 11th, or even that his experience would somehow shield him from what lay ahead in the days afterward.

The new commander of Company B was, as Bill Mauldin’s Willie and Joe — and even he — would later say, “a fugitive from the law of averages.”

The lieutenant had joined the 3rd Infantry Division as a private in North Africa. After serving for a time as a battalion runner because he was considered too frail for line duty (his friends called him “Baby”), he was eventually permitted to join the line as a combat rifleman with Company B in July 1943, during the Sicilian campaign.

For 19 months he had been pushing his luck, a quality that he appeared to possess in abundance. Only the day before he assumed command, his right leg had been sprayed with fragments from a mortar burst.

But compared to the mayhem he had already witnessed, his wound seemed so slight to him that he simply pulled out what fragments he could, applied his own field dressing, and continued his duties.

Two officers who had been commissioned with him were killed in the same barrage.

Now, on Jan. 26, the lieutenant moved his company through the Bois de Riedwihr. By early afternoon they had made their way to the edge of an open field, and as they walked into the clearing, the Germans opened fire with their usual murderous precision.

In the barrage, an American tank destroyer operating in support of the company was set afire, and abandoned by its crew.

Company B had gone to ground with the opening shot, and the lieutenant called for artillery counter fire.

In the meantime, large numbers of German infantrymen and six tanks advanced across the open ground, making for the American position. The lieutenant ordered his men to withdraw to the relative safety of the woods, while he remained to direct the artillery fire.

The Germans were not to be dissuaded, however, and they pressed their advantage.

Despairing of any more help from artillery, the lieutenant crossed ground swept by enemy fire, leaped aboard the burning tank destroyer, and turned its .50-caliber machine gun against the advancing Germans. As he worked the fearsome weapon, those of his comrades who could see him from the woods were sure that the lieutenant would soon be killed by ammunition exploding in the tank destroyer.

By this time, enemy tanks were actually abreast of his position, and he was under attack from three sides.

For the better part of an hour, an estimated 250 German infantrymen — two reinforced rifle companies — devoted themselves to killing the lieutenant, the only American then in their sights.

As many as 50 of them paid for their devotions with their lives. Finally the Germans broke off the attack, and the lieutenant, unscathed, left the still-burning tank destroyer to rejoin his men.

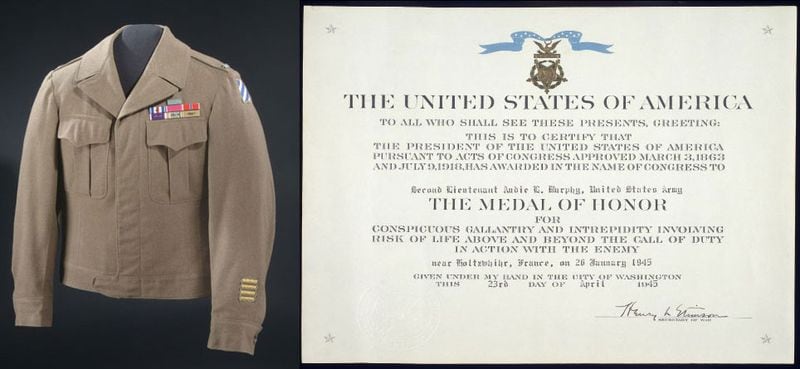

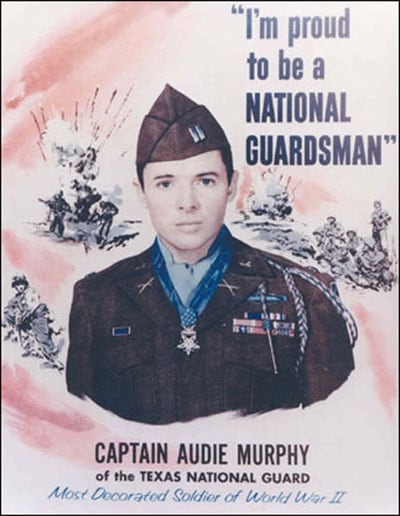

Four months later, in Salzburg, Germany, Audie Leon Murphy of Hunt County, Texas, stood nervously as Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch draped the Medal of Honor around his neck.

On that day, Murphy became the most highly decorated American fighting man not just in World War II, but in all of U.S. military history.

The Medal of Honor was Murphy’s 28th decoration. He had been awarded every other medal for valor in battle that the army had to offer, and several twice.

He was alive, more or less in one piece, and he was not yet old enough to vote.

Extraordinary valor in mortal combat has been celebrated in verse and rhetoric since Troy.

The hero’s deeds are commemorated and held up as examples of manly behavior worthy of imitation. A man who models his life on the hero, so the reasoning goes, prepares himself for the moment when his own finely schooled qualities will be called on.

At the moment of decision, the hero-aspirant must risk the possibility of annihilation, and in that moment his self-knowledge is pitted against forces beyond his control.

No wonder men who have performed in these uncertain regions of behavior have long had an air of mystery, as if their valorous acts were beyond reason or understanding.

The institutionalization of valor — the elevation of the soldierly hero as a publicly honored figure — originated about 200 years ago, when, in an age of enlightened reason, there evolved an attitude in the military that a soldier deserves something more than minimal pay, death, or crippling wounds in return for the honor of serving his country.

Napoleon, for example, although he thought little about marching his soldiers into the ground or wantonly spending their lives if doing so fit his plans, nonetheless was aware of the practical need to reward his men for heroic service.

But in this, as in so many other matters, Napoleon was precocious.

The British occasionally struck a medal to commemorate this great battle or that. The Waterloo Medal allowed its bearer two years’ credit toward his pension.

No doubt the ranks applauded even the smallest emolument for especially hard service. When, during the Indian Mutiny, Sir Colin Campbell — a very conservative commander when it came to handing out awards — implored his old regiment to make a special effort to break through enemy lines to rescue the British Residency at Lucknow, one soldier cried out, “Will we get a medal for this, Sir Colin?”

But it was not until the Crimean War that Britain established the fabled Victoria Cross. The Americans adopted a similar practice later still, creating the Medal of Honor in 1862.

In the early days the medal was relatively easy to win: One Federal regiment was given the award en masse (later revoked) simply for extending its Civil War enlistment.

The institutionalization of valor also served ulterior purposes.

Medals were given to foster morale among the troops and support for the war back home. Partly for this reason, with the proliferation of medals, their credibility became suspect among combat veterans. When pressed, modern soldiers will admit that it is better to have a medal for valor than not, but the medal mongering of the Vietnam War, for example, has created a cynical attitude toward battle decorations.

Most soldiers today do not feel that, with the exception of the Medal of Honor itself, awards mean very much. One highly decorated officer said recently that during his own experience in Vietnam, “the Silver Star was essentially a company commander’s good conduct medal.”

What can heroes tell us about themselves, other than that they are brave?

By revealing the details of their own behavior, they can tell us something about all soldiers in battle and about the phenomenon of battle itself. Since their lives are documented more than those of others, they offer us a window not only on themselves, but on the hidden lives of ordinary soldiers as well.

The difference between the two is not as great as we used to think.

Throughout history the most notable feature of the heroic act is that it transcends its military objective.

Commanders experienced in leading men into battle, for instance, are not at all certain that heroes are militarily useful. Most, given a choice between leading a battalion full of heroes and one of ordinary soldiers, would prefer the latter.

Successful military action depends on the commander’s ability to impose order on the chaos of battle, to turn his tactical ambitions into reality. This requires discipline and regularity of behavior, and neither quality seems to be common among heroes.

Clearly, it is not the lure of a medal that drives a man headlong into combat, risking death or dismemberment. Profounder motivations are required. The great puzzle is that most soldiers already possess these motivations and have acted on them through centuries of hard campaigning.

“The men know who deserve the medals and who don’t,” wrote S.L.A. Marshall in Colliers during the Korean War.

Marshall remembered one commander from the North African campaign of World War II who altogether stopped recommending his men for decorations, because invariably those least deserving awards received them, while true heroes did not.

Marshall claimed that during World War II, an unwritten rule prevented combat medics — the one class of soldier whose life expectancy was actually shorter than the combat rifleman — from receiving any award higher than the Silver Star. Thus, the awarding of medals was too erratic to be just. There could be little assurance among the men that the ribbons over a man’s pocket told the real tale, and most men were a little bashful about wearing them at all.

A hero’s immediate comrades tend to know the truth about him, but among other soldiers, he is naturally somewhat distrusted.

An officer who served in the 3rd Infantry Division admitted that Murphy “was not the most admired guy in the world.”

There are good and practical reasons for the ordinary soldier — whose first ambition is to survive the day, the next day, and perhaps even the war — to cock an eye at the consistent hero. Even though his actions are public, the hero is often a solitary soul who depends chiefly on his own passions, skills, and luck.

It is his aloneness that singles him out. He tends to get killed, and his comrades with him. Worse, he sometimes survives while his comrades do not. Of course, this may be only luck — the bullet or shell just did not have his name on it that day — but you can easily sympathize with the suspicions of the ordinary soldier.

The bonds among the men in the smallest fighting units of World War II were extremely strong. The great wartime cartoonist Bill Mauldin, a perceptive observer of men in combat, believed that “you will seldom find a misfit who has been in an outfit more than a few months.” (Those who could not fit in usually ended up dead or invalided to the rear.)

And as for those occasions when someone in a unit is a candidate for an award, Mauldin added that “his friends are so willing to be witnesses that sometimes they have to be cross-examined to make sure they are not crediting him with three knocked-out machine guns instead of one.”

After Murphy’s action in the Bois de Riedwihr, he was pulled out of the line.

Witnesses provided affidavits, and, within the month, the division had begun processing his award. By taking Murphy away from his unit — infantrymen were in very short supply in those days — the division signaled its view that the award would probably be the Medal of Honor.

None other was sufficient to warrant relief from combat.

Murphy was, after all, a rare commodity — a living and relatively undamaged candidate — and the authorities very likely did not want to risk losing him. (Capt. Maurice Britt, also of the 3rd Division, had been recommended for the Medal of Honor during the Italian campaign, but he had stayed on the line, only to lose an arm in a subsequent action.)

Murphy was promoted to first lieutenant, given a leave to Paris, and, upon his return, reassigned as a liaison officer to his regiment. This change of duty improved by a large margin his chances of surviving the war.

There is no evidence that he complained.

In his letters home about this time, Murphy frequently mentioned his medals, especially the Purple Hearts. But he seems to have regarded them more as war souvenirs, booty to be sent home, than as badges of soldierly courage.

He understood that a Medal of Honor would get him out of the line, and that was the main reason for his enthusiasm when he learned he might get one. On April 1, 1945, he wrote to friends that he had been given the Distinguished Service Cross, a Silver Star, and a Bronze Star, and then was waiting at regimental headquarters for the Medal of Honor to be awarded, “so I can come home.”

That, along with the Legion of Merit he was about to receive, meant that “since that is all the Medals they have to offer (I’ll) have to take it easy for a while.”

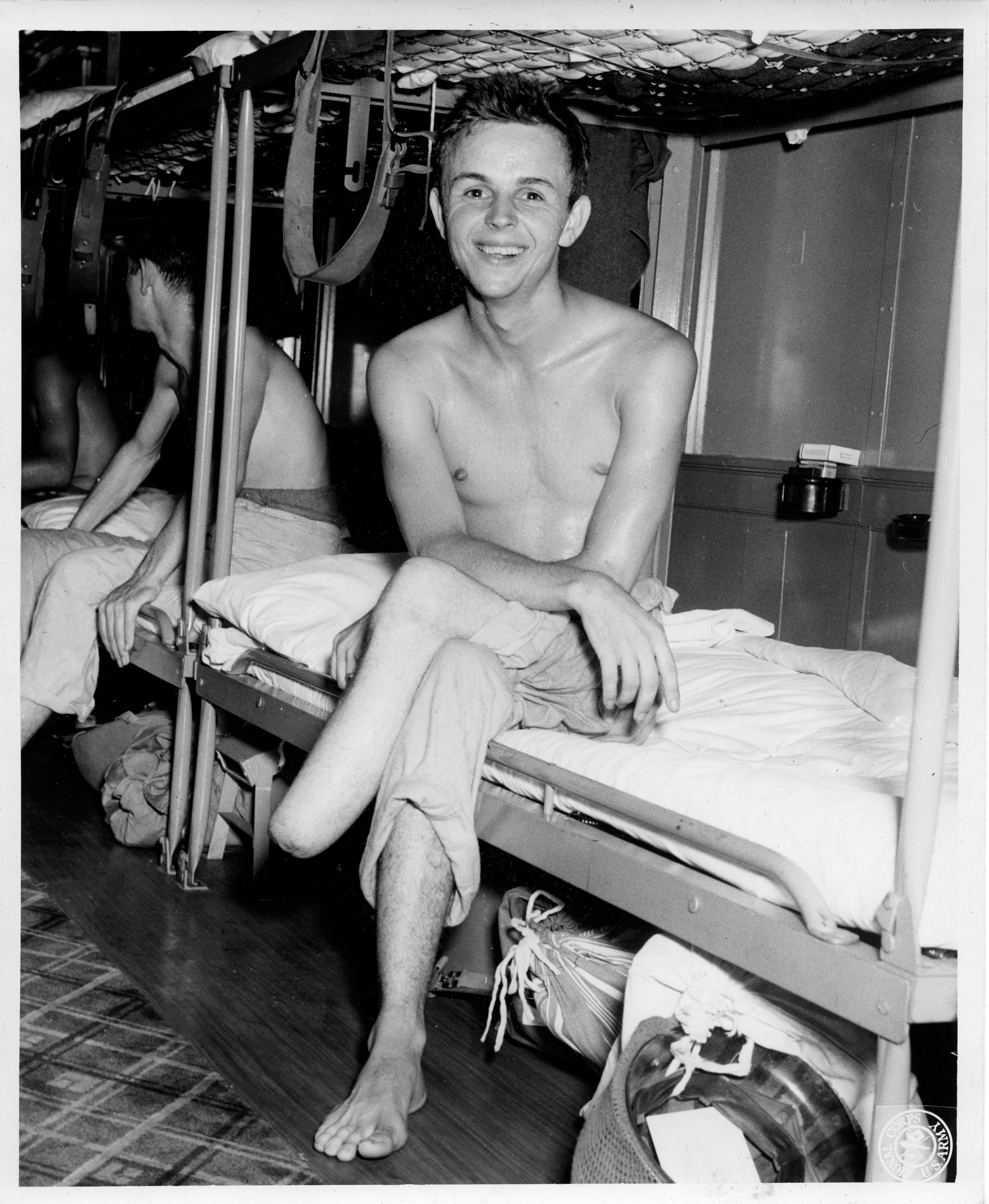

Eleven days after receiving the medal, Murphy stepped off a plane at San Antonio and, in company with other military notables from Texas, began a round of parades, toasts, speeches, and interviews, slowly working his way north to Hunt County.

To the crowds that gathered around him that summer, Murphy was no doubt befuddling and endearing. He was not the iron-eyed, athletic, self-contained warrior Americans seem to expect their military heroes to be. He was not tall and muscular, and he did not swagger. He was very slight, soft-spoken, and wearily uncomfortable with all the attention. But for the tan officer’s uniform, bristling with ribbons, he could have been the kid next door.

The actor James Cagney, soon to be instrumental in helping Murphy get his start in motion pictures, said that what was appealing about Murphy was his “assurance and poise without aggressiveness.”

Murphy certainly did not look like the kind of man who might have spent nearly two years fighting his way from the hills of Sicily to the German frontier in the worst kind of infantry combat. In the story that accompanied his cover photo in Life magazine in July, there is a picture of the lieutenant getting a haircut at Mrs. Greer’s barbershop in Farmersville, Texas, near his home.

Outside the big plate-glass window there stands a crowd of more than a dozen men, simply staring at him. There is an expectant air about the crowd, as if Murphy might suddenly bolt from the chair and do something hero-like. His head is bowed and the barber’s bib drapes across his knees. He looks very young and mortally tired.

What Murphy was about to discover is that the hero’s deed is only the down payment on the price he must pay for acclaim. Frequently the medal becomes a curse for the man who wears it.

Some 111 men received the Victoria Cross during Britain’s 19th-century campaigns. Seven of these subsequently took their own lives, a horrendous rate for a time when in the general population there were only 8 suicides per 100,000.

Still more had utterly disastrous postwar lives, finding that they were unequal to the more pacific rhythms of life beyond the battlefield.

We know of the sad fate of the popular Marine hero Ira Hayes, who assisted in the raising of the flag on Iwo Jima’s Mount Suribachi; but no complete study of the postwar fates of medal winners has ever been done.

Of course, you need not be a certified war hero to suffer problems after a war, but the hero may carry a heavier burden than the ordinary soldier. As it was put by Capt. Ian Fraser of the Royal Navy, a Victoria Cross recipient in World War II, “A man is trained for the task that might win him a VC. He is not trained to cope with what follows.”

It is when you consider Murphy’s record in context that his valor becomes truly impressive.

During World War II, 433 Medals of Honor were awarded, 293 of them to soldiers. Thirty-four, or 11.6 percent, went to men in Murphy’s own 3rd Infantry Division, the most remarkable fighting organization in that war, during campaigns from North Africa to Germany. Fourteen were awarded to Murphy’s 115th Infantry Regiment alone.

The 30th and the 7th also had an unusually high record of Medal of Honor awards, making the 3rd Infantry Division the most highly decorated American unit in the war.

The division’s record naturally poses questions: Compared to others, was the 3rd somehow a better fighting organization? Did it have a more difficult, longer war? Were its leaders especially sensitive to the benefits of soldierly morale, and therefore did they apply more often for awards? And did Murphy’s membership in the 3rd somehow encourage him to perform valorous deeds repeatedly?

Unquestionably, the 3rd Infantry Division was a fine fighting organization. It was a “heavy” infantry division as it entered the war during the North African campaign, carrying more than 15,000 troops on its rolls.

During the war, it participated in four amphibious landings, fought in 10 separate campaigns, and was in contact with the enemy on more than 500 days, with few opportunities to rest and refit.

According to the testimony of one of its wartime commanders, Lucian K. Truscott, Jr., “few divisions have ever entered action in a higher state of combat efficiency.”

Truscott was a very plainspoken cavalryman, not given to hyperbole, and he was one of the very best division commanders of the war. But the appraisal of one’s enemies always carries more weight.

After Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, the German theater commander in Italy, was captured, he was asked to rate the quality of the units his armies had fought. He replied that the 3rd “was the best division we faced and never gave us a rest.”

And then there are the numbers.

Recently, when an officer who served with the division early in the war was asked about the official view of the awards, he agreed that the 3rd had more than its share; then he added, “Have you looked at the casualty figures?”

Essentially, the division’s membership turned over five times during the course of its campaigns. Battle and non-battle casualties amounted to a staggering 74,044 soldiers by the division’s own count.

Of these losses, Truscott reported during the fighting in Italy, 86 percent were in the infantry battalions.

After the first thirty days of fighting, the infantry companies were at half strength, “although,” recalled Truscott, “it had not seemed from day to day that losses were excessive.”

Unfortunately, divisional battle streamers and casualty figures tell us very little about what the soldiering — the ordinary soldiering — was like.

Well after the war, one army psychiatrist attempted to profile “normal” combat reactions; the result was a picture of a bedraggled, haggard, near neurotic, suffering from vague physical complaints, inability to concentrate on the task at hand, constant irritability, and, in general, uselessness for any sort of strenuous activity — certainly not combat.

During the war, both Bill Mauldin and Ernie Pyle tried to describe for the public back home what the front was really like. In the end, both would have agreed with the British army’s Capt. Athol Stewart: “Do you know what it’s like? Of course you don’t.”

In their reminiscences, veterans often despair of recalling the details of actual combat. Threading throughout their attempts at memory are references to “dreamlike states” and “floating,” and in the more modern language of Vietnam, “out-of-body experiences.”

The novelist John Steinbeck, working as a war correspondent in Italy during some of the campaigns Murphy fought in, believed that combat is beyond the powers of memory to reproduce.

“You try to remember what it was like, and you can’t quite manage it,” he wrote. “The outlines in your memory are vague. The next day the memory slips farther, until very little is left at all…Men in prolonged battle are not normal men.”

So combat riflemen like Murphy stood at the farthest and most dangerous end of grand military enterprises, where elegant strategies and refined tactics count for little. Those matters belong to a world bounded by traditional military science. When a soldier moves forward against fire, he steps beyond the boundaries of anything we understand.

Then, centuries of military science are at the mercy of one bullet, and if reason is at play it must expend its power in forms so different that they have eluded us thus far.

For Murphy and his comrades in Company B, the authors of all their miseries were, of course, the Germans. From the time Murphy entered the line until his last day in combat, his enemies were on the strategic defensive and largely on the tactical defensive as well.

In the terrain he had to cross, the advantage naturally rested with the defense, and at this the Germans were very, very good.

After the fighting around Mount Fratello, Murphy wrote, “I acquired a healthy respect for the Germans as fighters” and “an insight into the furies of mass combat.”

That action, he recorded, had “taken the vinegar out of my spirit.”

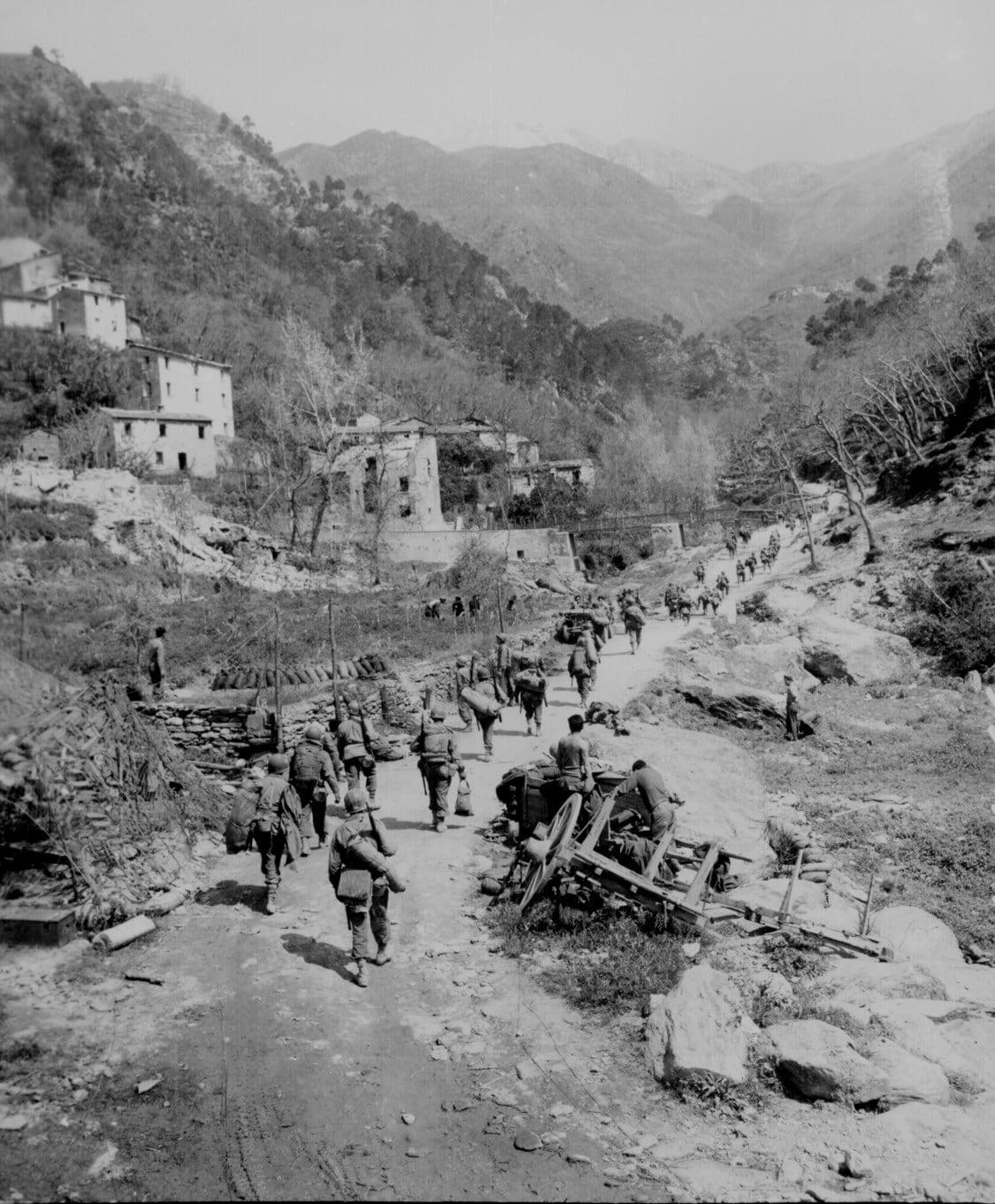

The Italian campaign was the worst yet for the 3rd Division.

Casualties between the Allied landings at Salerno and Anzio amounted to more than the authorized strength of the division; as usual, the line units suffered the most.

Because of the atrocious weather and the limitations it imposed on motorized tactical movement in monotonously hilly terrain, troops were often stranded in the lines for several days without food or water.

Mules were pressed into service to carry needed supplies when enemy fire subsided. The enemy gave ground grudgingly.

Murphy participated in several attacks during this time, attacks that succeeded less because of the power of assault than because of shrewd maneuvering. Often, the enemy seemed impervious to anything the Americans tried.

“If the suffering of men could do the job, the German lines would be split wide open. But not one real dent do we make,” Murphy wrote later of the fighting around Monte Lungo.

When the enemy did give ground and the Americans occupied it, the Germans routinely shelled their old positions.

Murphy survived the Italian campaigns as a staff sergeant, with two Bronze Stars for valor, in command of a platoon — a position normally held by a second lieutenant. He had not been wounded, although he had been one of his division’s 12,000 “nonbattle casualties.”

Meanwhile, he had come to the attention of his commanders as a canny soldier who possessed extraordinary combat sense. Insofar as a soldier could be battle-wise, Murphy was.

The wisdom of battle exacts its price, however.

During the war, researchers found that after the initial fear of combat passed, the ordinary soldier was likely to relax somewhat, take more chances, and in some cases harbor a feeling of indestructibility. That feeling would be challenged eventually by the grind of daily action, or more promptly by two dramatic events: a wound or a near miss, or the death of a close friend.

Both were about to happen to Murphy.

On the morning of Aug. 15, 1944, Allied troops invaded southern France, coming ashore south of Saint-Tropez.

Military historians would later debate how relatively light the German defenses were compared to those at Normandy, and how easily the Sixth Army Group moved northward along the Rhone against a rapidly retreating German army.

But invasion day was a very bad one for Murphy.

Near the town of Ramantuelle, his best friend was killed when enemy troops played a false surrender. After his friend died in his arms, Murphy embarked upon a frenzied and singlehanded assault, eventually killing or wounding 13 German soldiers.

“I remember the experience as I do a nightmare,” he wrote; “the men…tell me that I shout pleas and curses at them, because they do not come up and join me.”

Murphy received the Distinguished Service Cross for his mad spree at Ramantuelle; no doubt he would have preferred the survival of his friend.

After a quick and cheering advance along the Rhone, the Sixth Army Group entered the Vosges Mountains, and all of a sudden the fighting seemed reminiscent of Italy.

By this time, nearly all of the original members of Company B were gone — killed or wounded. Murphy began to withdraw into a fatalistic alienation from his fellow soldiers. The comradeship that had originally sustained him had been gradually shot away and could not, would not, be regenerated.

Although still in the midst of his fighting company, Audie Murphy was essentially alone.

Remembering this bleak time, in his autobiography, To Hell and Back, Murphy wrote:

So many men have come and gone that I can no longer keep track of them. Since Kerrigan got his, I have isolated myself as much as possible, desiring only to do my work and be left alone. I feel burnt out, emotionally and physically exhausted. Let the hill be strewn with corpses as long as I do not have to turn over the bodies and find the familiar face of a friend. It is with the living that I must concern myself, juggling them as numbers to fit the mathematics of battle.

As remarkable as his survival was the fact that Murphy had not by then succumbed to combat fatigue.

Among the frontline troops, the conventional wisdom was that everyone had his “breaking point” if he stayed in the line too long. Nor did respite from battle, such as Murphy had had while training for the landing in southern France, particularly help in warding off that breaking point.

Paul Fussell, the author of the acclaimed book The Great War and Modern Memory, but earlier a company commander with the 45th Division in the spring of 1945, recalls his experience after he returned from the hospital to the combat lines.

His convalescence “helped me survive for four weeks more but it broke the rhythm and, never badly scared before…I found for the first time that I was terrified, unwilling to take the chances that before had seemed rather sporting.”

By October 1944, both of the opposing armies were wearing down. Generalmajor Wolf Ewert, the commander of the German 338th Infantry Division then opposing the Sixth Army’s advance, reported losses as high as 60 percent in the battles for Alsace. The casualties among the officers and non-commissioned officers were especially high.

On the American side of the lines, infantrymen were at a premium, and as the winter approached, manpower shortages became severe. Having earlier refused a battlefield commission because it would separate him from his men — newly commissioned officers were routinely transferred to another unit — Murphy accepted his commission on Oct. 15, with the understanding that he could stay with Company B.

His regimental commander, Col. Hallett D. Edson, pinned the gold bars on Murphy’s shirt and told him to get a shave, take a bath, “and get the hell back to the front lines.” Twelve days later, Murphy was seriously wounded by a sniper.

Getting to the field hospital took too long; Murphy’s infected wound became gangrenous. He remained hospitalized for the rest of the year. When he finally returned to Company B, the unit was getting ready to penetrate the Colmar Pocket in the direction of Holtzwihr.

However, the Bois de Riedwihr lay across their line of march, and it was within these woods that Murphy’s fame awaited.

During World War II, battles often took place inside what the Germans knew as der Kessel, “the caldron.”

The phrase evokes the stuff of close combat in confined spaces, the abiding and numbing fear of the next step that grinds down the swift movement of armies. To a degree perhaps not appreciated by modern military historians, World War II was one of places and lines.

The rapier’s thrust, typified by the dash across France, was an exception in this war. Eventually, the men who did Murphy’s kind of work had to take the ground away from their counterparts on the other side of the main line of resistance.

For the better part of two years, Murphy lived inside der Kessel. As we shall see, he went to some lengths to get there, believing, as many do, that within war were mysteries of self to be discovered, and of worlds beyond the life of a Texas sharecropper.

In Stephen Crane’s classic story of the soldier’s rite of passage, The Red Badge of Courage, the young hero, Henry Fleming, is overtaken by a desire to see war. He frets that war might be too modern to permit the attainment of real glory. He wonders if “he might be a man heretofore doomed to peace and obscurity, but, in reality, made to shine in war.”

Remarkably — all the more so since Murphy later played Henry Fleming in the movie version of Crane’s book — Murphy seems to have been “made to shine in war.”

No one tried harder than Murphy to see, as Henry Fleming did, “the great Red God of War.”

Whether Murphy had a predisposition for war is a problematic question, but there is little doubt that he saw the war, as innocents often do, as a way of escaping the grinding poverty that had so far dominated his young life.

He was drawn to the elite units: The Marines were first on his list. Rejected twice, he tried to enlist for duty with the new airborne units, but he stood 5-feet 6-inches and weighed only 112 pounds — less than the battle gear the troops were often obliged to carry.

Finally, he was made to settle for the infantry — unhappily, as “the infantry was too commonplace for my ambitions,” he wrote later.

Caught up in the great mobilization, Murphy was shifted from one post to another; at each place well-meaning superiors attempted to protect him from a combat assignment.

“Fuming,” he recalled, “I stuck to my guns. ”

He was still just a child, really, when “Finally the great news came. We were going into action…”

Audie Murphy was so adept at infantry combat that we are compelled to look for reasons. He was certainly willing, even earnest, to join the rush to the colors, but most recruits are willing in the first flush of war.

Reality quickly cools the new soldier’s ardor. Murphy did not cool quite so quickly.

Despite his small size, he had the stamina that comes from years of farm work, but it cannot be said that he was any better prepared for the physical rigors of combat than anyone else.

After a few weeks on the battle lines, infantrymen are usually in terrible physical shape. Long before he was wounded, Murphy spent several days in hospitals, suffering from respiratory ailments acquired in Sicily and Italy.

He had plenty of company.

Murphy appears to have believed, and his home state was quick to claim, that having been born and reared in Texas had something to do with his military success.

But pride in origins should not be confused with some sort of predestination. He was a rural boy, of course, accustomed to hunting in the hills and valleys of North Texas. The countryside and its forms held no mysteries for him.

But these advantages, if advantages they were, can be noted only as indecipherable factors.

Most Americans who fought well in the war were not from Texas and had been no closer to the country than the city park before they enlisted. How they performed in combat had more to do with what the great German military historian Hans Delbrück would have called “the material possibilities of the moment.”

And despite a great deal of official interest by the U.S. Army since World War II, a psycho-physical profile of “the natural fighter” has never been done.

Whether Murphy’s behavior predisposed others to think of him as valorous is another question. It is true that even the most ordinary rifleman took terrifying risks day after day, but Murphy’s practices were not typical.

During his war, Murphy developed certain habits that automatically brought him to the approving notice of his superiors. Before the war he had been pugnacious, and this temperament served him well during his campaigns.

And although he was as comfortable with his comrades as any combat soldier might be, he was given to independent action. He often volunteered for patrols to gather information or to take prisoners. Frequently, he would “go hunting,” and, when he did, enemy snipers were in danger.

As he gradually acquired command responsibilities, he usually would see his men safely placed, then go forward alone or with a couple of others to reconnoiter the ground ahead.

For Murphy, then, the sequence of events during his action at the Bois de Riedwihr was not so unusual.

Nor was his endurance of notorious stresses unusual, at least for him.

One officer of the 1st Scots Guards who fought in Tunisia recalled seeing “strong, courageous men reduced to whimpering wrecks, crying like children.”

Murphy never seems to have had such a breakdown, although he had more than his share of reasons to do so.

He seems, on the contrary, to have been able to redirect his reaction to stress against the military objective at hand.

Obviously, stress was at play during the incident at Ramantuelle. Since the last century, military theorists have recognized that one of the many ways to escape immediate danger in combat is to move forward; Murphy did that more than once.

All of which is not to say that Murphy escaped suffering, either in the war or after it.

After the sniper’s bullet in Alsace proved he was not, after all, invulnerable, he adopted the fatalistic attitude common to soldiers long at war. From his hospital bed, he wrote home that “these Krauts are getting to be better shots than they used to be or else my (luck is) playing out on me. I guess some day they will tag me for keeps.”

After he was recommended for the Medal of Honor and reassigned to his regimental headquarters, Murphy’s luck was tested less often; but there was plenty of war left, and on several occasions he was drawn into combat, despite the Army’s desire to preserve the life of a Medal of Honor winner.

And then, finally, the war ended. But Murphy’s private war did not.

In ages past, once the colors were furled, soldiers gratefully went home. The signing of the peace was a signal for nation and individual alike that normal life could be resumed.

But during this century there have been disturbing signs that the psychological effects of war are rather more persistent than anyone wants to think. The medical world has devised increasingly sophisticated interpretations of the spiritual lassitude, and worse, that seems to affect so many veterans.

What was “shell shock” in World War I was gradually re-described as “combat fatigue,” or “neuropsychiatric casualty,” in World War II, and finally as “post-traumatic stress” in the Vietnam War.

So, too, did the supposed causes of the malaise change. Whereas shell shock was thought to be the result of concussions and gas from high explosives, combat fatigue was believed to be a pernicious mixture of the soldier’s personality and the immediate stresses of combat.

In the years since Vietnam, interpretations have tended to emphasize the stresses of combat alone as the cause of postwar emotional suffering.

Of course, there were vast differences among all these wars — the circumstances under which men fought, as well as the conditions they found at home upon their return.

Students of the Vietnam era have noted that Vietnam veterans did not have the advantage of returning World War II soldiers, who came home in troopships, where they could “decompress” for at least several days.

The flight from Saigon to San Francisco took only about 18 hours; afterward, soldiers were discharged and left to their own readjustment — or lack thereof.

Murphy’s experience more nearly matched that of the Vietnam vet. Even with his own generation’s opportunity to relax before discharge, Murphy thought, returning vets were poorly handled.

He told an interviewer in 1960 that “they took Army dogs and rehabilitated them for civilian life. But they turned soldiers into civilians immediately and let ’em sink or swim.”

To be sure, Murphy’s own postwar experience was unusual.

Few other vets became national institutions. As his fame spread, one Dallas newspaper sought to tell the public “what Murphy is like — a swell kid, absolutely modest, sincere and genuine and unaltered by terrible experiences.”

Well, not quite, because while other veterans were allowed to contend with their personal demons in private, every event in Murphy’s life after the war was played out in public. His skills did not easily translate into civilian life, and he clearly was unsure what to do when the cheering stopped.

Fortunately, before too long he was recruited by Hollywood, much as sports heroes are today.

His photograph on the cover of Life had inspired James Cagney to invite him west. Originally intending to register Murphy at a hotel, Cagney was so startled by Murphy’s fatigued appearance that he offered the young man the use of his pool house instead.

Murphy was Cagney’s guest briefly, went home for a visit, and then returned to spend nearly a year at the actor’s home.

Within five years Murphy had parlayed his wartime fame into a peacetime career.

The movie career has been depicted as modest. Film histories do not mention his work — perhaps wrongly, for he was cast perfectly in John Huston’s The Red Badge of Courage and Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s The Quiet American.

Murphy himself took a dim view of his acting ability and did not seem to think of his career as more than a way to make a decent living.

“I didn’t want to be an actor. It was simply the best offer that came along,” he recalled long after the war.

But he certainly did well enough: By the early 1950s, Audie Murphy had enough box-office power to demand script and director approval (as well as the lead role) for any movie he was in.

Yet the two years he spent in the caldron of war dominated his life and, to an extent that could be known only by himself, determined its course. His wartime heroism overshadowed everything he did, although by most standards he made a greater postwar success of himself than his early history would have suggested.

Without that vital identity as a military hero, Murphy might well have returned to a quiet life in rural Texas, never to be touched by fame.

Ironically, perhaps, it was that fame that kept the war too much alive for him. Decades after the war, he still could not relax. He had chronic stomach complaints, sensitivity to loud noises, and frequent nightmares.

He always kept the bedroom lights on at night and a loaded pistol by his bed. Sometimes he carried the pistol.

Murphy’s fortune declined in the 1960s: He had always gambled, but the habit began to get the best of him then. As bankruptcy threatened, he grasped at dubious business schemes and acquaintances.

His political outlook, always on the conservative side, verged on the extreme.

But none of these difficulties strike us today as particularly the effect of trauma. Indeed, we are so accustomed to heroic figures who fall from public grace that the concept of heroism itself has devolved.

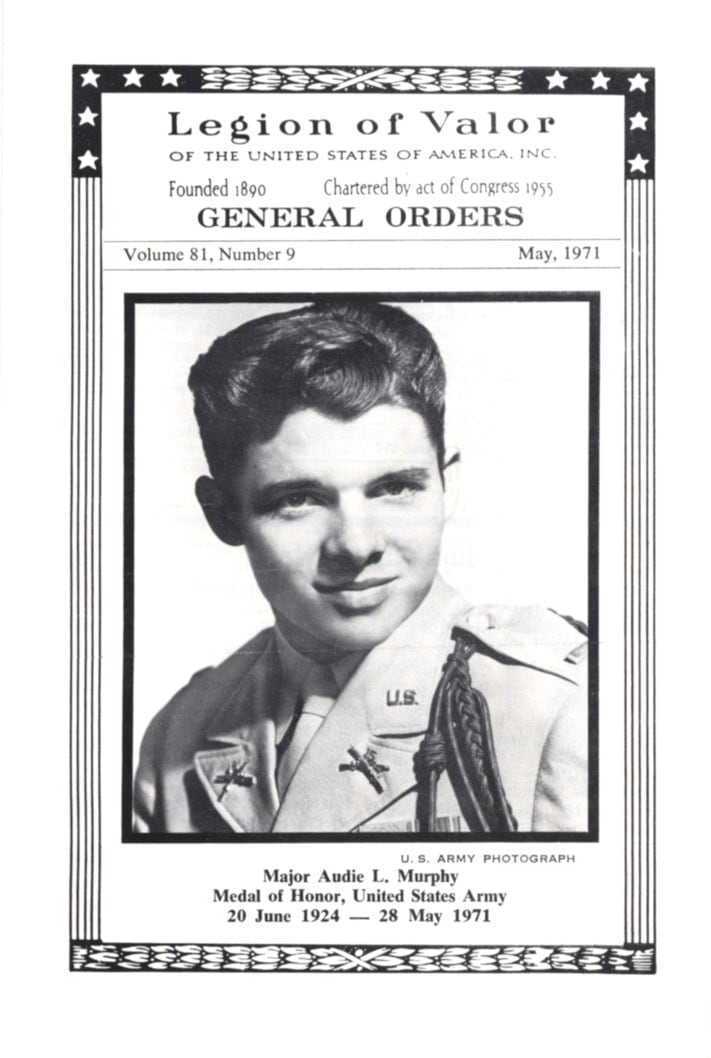

When Murphy was killed in a plane crash near Roanoke, Virginia, in 1971, he still seemed incomplete, searching for something elusive.

Once asked whether men get over a war, he had replied reflectively, “I don’t think they ever do.”

Before his death in 2017, Dr. Roger J. Spiller had served as the George C. Marshall Professor of Military History at the United States Army Command and General Staff College, Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. An Air Force veteran born about 35 miles north of Audie Murphy’s hometown, he helped transform the Combat Studies Institute in an Army think tank and collaborated with filmmaker Ken Burns on this televised series about World War II, The War. This article originally appeared in the Spring 1993 issue of Military History Quarterly, a sister publication of Navy Times.

RELATED