As the aircraft carrier Dwight D. Eisenhower and its thousands of sailors got ready for another deployment this fall, one officer was worried.

Ike broke records earlier in 2020 by deploying for 206 consecutive days at sea, a dubious distinction of a cruise made longer and crappier by the need to keep the crew COVID-19-free, eliminating the port calls that serve as pressure release valves for hard-working shipmates during deployments.

The carrier got back to Norfolk in August and will soon ship out again.

As this so-called “double pump” deployment looms, an Ike officer, who asked not to be named for fear of retribution, is readying for the worst.

“Much of leadership I have spoken to or heard of is legitimately concerned about morale, thinking suicides during the upcoming deployment are inevitable at this rate,” the officer said. “And no one can explain, for what?”

RELATED

The officer’s concerns come as Big Navy’s COVID suppression measures are placing added stress and strain upon sailors and raising questions in some circles about retention and the material readiness of Navy ships, compounding issues that existed well before the pandemic.

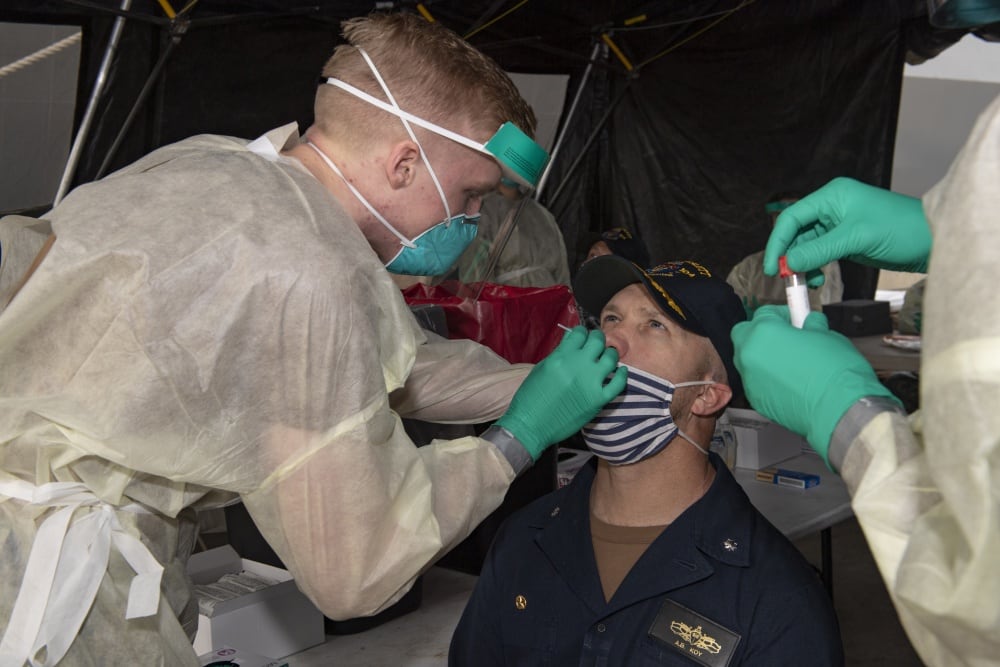

The Navy has already started vaccinating health workers and other members of the fleet most at risk, and most sailors are likely to be vaccinated this year.

But coronavirus precautions continue to force crews to quarantine on ship between pre-deployment training and shipping out, cutting into family time and leading to cruises without port calls.

Some are wondering why the Navy continued to push the operational pace last year, as if COVID-19 didn’t even exist.

Bradley Martin, a retired surface warfare officer who spent two-thirds of his 30 years in the Navy at sea, fears that this year’s pace is going to prematurely wear out both sailors and their ships.

COVID has made the surface fleet’s readiness crisis that much worse, he said.

“I can’t imagine that somebody is going to say after all this, ‘what I really want to do is stay in the Navy and do back-to-back deployments were I never even go into port,’ ” said Martin, now a senior policy researcher with the Rand Corp. “That doesn’t sell itself.”

The Ike officer said sailors cannot understand why Navy crews and families are being put through such a frenzied pace in peacetime, which could leave the fleet unprepared should real war break out.

RELATED

“I have never dreamed of watching a crew get put through something like this,” the officer said. “We are not at war and this type of op tempo will put us at a disadvantage if we ever do end up in real conflict.”

The officer fears many sailors are already eyeing the exit as a result.

“COVID procedures and our op tempo has been horrible for morale and retention,” the officer said. “Sailors and their families are hurting, with very little time between all of the work up detachments and underway, and they have nothing to look forward to for an unforeseen future.”

“Retention from this crew as a whole will take a major hit in the long-term,” the officer added. “I wish someone would take a survey to see how truly widespread this specific issue is.”

The brass insists it is hearing these concerns, and efforts are underway to tweak family separation pay and other benefits to lessen the sting of longer deployments.

Big Navy stresses that such measures aimed at creating “COVID-free bubbles” aboard ships are critical to ensuring that another crew doesn’t suffer the kind of mass outbreak that afflicted the aircraft carrier Theodore Roosevelt this spring, when roughly a quarter of the ship’s crew was infected.

Still, more than 200 ships suffered some sort of COVID outbreak last year, though most have been quickly isolated and mitigated, according to a message to the fleet this fall by Chief of Naval Operations Adm. Mike Gilday.

Ashore, some sailor weren’t allowed to go home this holiday season and have endured restrictions on their off-duty activities as well.

Vice Adm. Phillip Sawyer, deputy chief of naval operations for operations, plans and strategy, acknowledged these difficulties in October.

“Getting COVID-free and staying COVID-free is a challenge and it comes at a cost,” he said. “We know these mitigations are hard on our sailors and their families.”

RELATED

“But it’s a critical piece of protecting our sailors who have signed up to serve,” Sawyer added. “All of this is about keeping our sailors safe.”

Fleet Master Chief for Manpower, Personnel, Training and Readiness Wes Koshoffer also acknowledged how difficult this year has been during a Facebook townhall event.

“We know the fatigue is real and it’s had an impact,” he said. “We’ve asked a lot of you this year.”

And even though vaccines are starting to roll out, Koshoffer cautioned that “unfortunately, we’re not done yet.”

The Ike hasn’t been alone in a brutal operations tempo made worse by the threat of the pandemic in 2020.

Several ships have broken records for consecutive days at sea during deployments this year, an ignominious championship belt held by the men and women of the warship Stout.

The destroyer limped back to Norfolk in October, following a nine-month deployment that began in January, when COVID-19 was barely on the radar of any American.

All told, Stout’s shipmates grunted through 215 consecutive days at sea, eclipsing Ike’s 206-day record during a cruise that involved shortages of food, parts and fuel.

Stout also made history by becoming the first Navy ship in modern times to complete a so-called “mid-deployment voyage repair” while at sea.

“We’ve gone for significant lengths of time without new parts, stretched our food and fuel limits, and they continued to give 110 percent every day,” the ship’s commanding officer, Cmdr. Rich Eytel, said of his sailors in a statement at the end of the deployment. “They faced our challenges head on, which allowed us to continue to meet all operational tasking.”

RELATED

‘Their worst cruise’

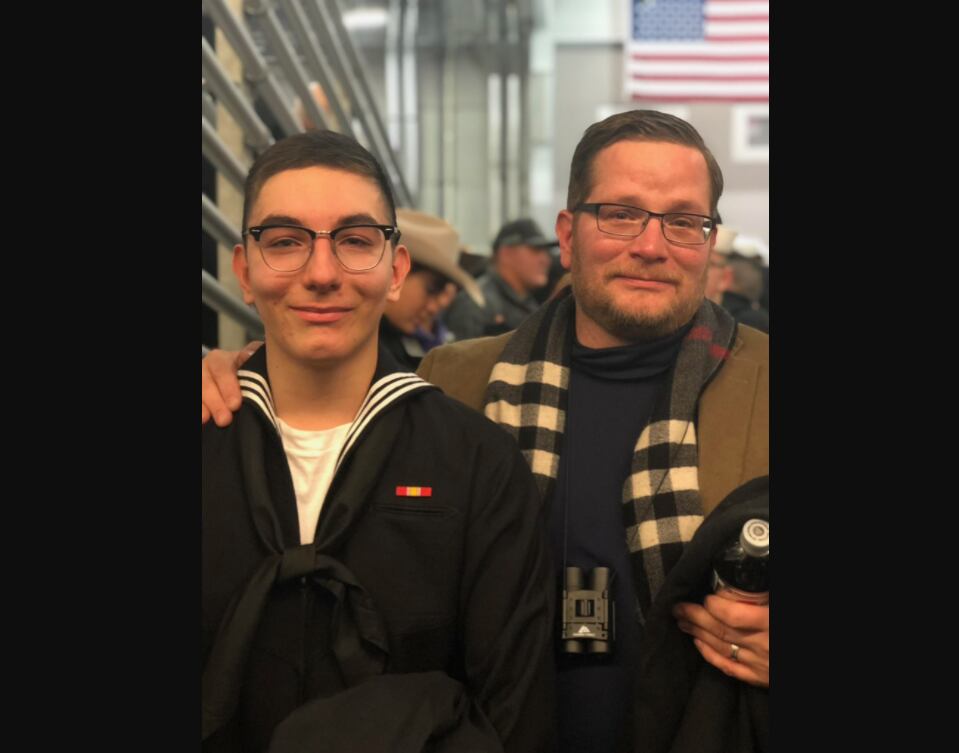

Like Stout, Ike left in January 2020, enjoyed zero port calls and returned to a very different America in August.

Among Ike sailors, that cruise was the “unanimously agreed upon worst deployment in recent memory,” the Ike officer said.

“Ask any crusty chief who has deployed multiple times on any number of ships, and it was all of their worst cruise,” the officer noted.

The officer noted that the carrier Nimitz pulled into Duqm, Oman, in September, but the Ike wasn’t afforded such a stop.

“The easy conclusion for everyone to draw here is that Duqm was an option for Ike and that keeping her out of port was a deliberate decision,” the officer said. “All our captain could talk about was breaking the (consecutive days at sea) record, which Stout quickly overtook.”

Even a restricted port call on the pier would have helped the weary crew, the officer said.

“Any sailor on that ship would have gladly traded a 5-minute FaceTime with their family for that record,” the officer said.

A silver lining of the Ike’s deployment last year was that the shipmates were already underway as the pandemic exploded.

They stayed at sea COVID-free and didn’t have to mask up or undertake other Navy precautions aimed at mitigating spread in the ship’s cramped quarters.

But as the Ike gets ready for another deployment, they are subject to the Navy’s COVID measures, some of which the officer deemed a contradictory “disaster.”

“Seating and headcount are limited on the mess decks and in the wardrooms, which leads to huge lines wrapping through the p-ways, with extended time standing shoulder to shoulder,” the officer said. “We cannot serve ourselves, but we can touch the same handles, hatches and rails all day? It’s okay to not wear a mask when you’re smoking but you have to wear it while exercising?”

RELATED

The officer told Navy Times that the crew began pre-deployment isolation in area hotels starting Dec. 28.

This chaps the officer, who said the unit that will certify them as ready for deployment is being allowed to quarantine at home with their families.

“Everyone that I know believes that the admiralty making these decisions while they sit at home with their families are completely out of touch and have the blood of any mishaps or suicides on their hands,” the officer said.

Ike sailors in ROM got Navy meals the officer characterized as subpar delivered to them and were not allowed to order delivery or exercise outside their hotel room.

“No drop offs from your family if you forgot something,” the officer said. “Mass pain and stress on all hands. Out of touch admiral level leadership suggesting calling and FaceTiming our families and ‘learning a new language during ROM’ to prove resilience. Unbelievable.”

Navy officials said sailors assigned to the Ike’s air wing and strike group began ROM on Dec. 27, and were cleared to embark their vessels following a negative test, usually two to three days after the result.

Out in San Diego, Theodore Roosevelt quietly began its own back-to-back deployment in December, months after the carrier returned home following this year’s harrowing COVID cruise, when roughly a quarter of those onboard caught the virus, prompting an emergency months-long detour to Guam.

A few days into the cruise, Aviation Ordnance Airman Apprentice Ethan Goolsby went missing and overboard from the ship, prompting a dayslong search for the junior sailor.

RELATED

His parents told Navy Times he was exhausted and overworked, and that he had been made to quarantine alone in a room for weeks.

In October, another TR sailor, Seaman Isaiah Glenn Silvio Peralta, fatally shot himself while standing watch on a San Diego Navy pier.

Several TR spouses told Navy times this fall that the outbreak and continuing with the scheduled double pump was just too much.

“It’s taken a toll on everyone’s mental health, everyone that I know from the ship,” one spouse said. “It’s draining and exhausting, and it never ends.”

“Every single day with this ship is exhausting.”

“We always thought we were going to be long term, stay in 20 years,” another TR spouse told Navy Times.

But last year’s events “put into perspective that we’re just numbers and not people,” the spouse added. “It’s really changed both of our outlooks.”

“They’re trying to act like (this year’s TR deployment) wasn’t a big deal,” the spouse said. “I don’t think they’re taking into consideration the impact, mentally and physically, that the deployment took on them.”

The long-term effects

Some Navy watchers are wondering how 2020 will affect the ranks and the ships on which they serve.

Martin, the retired SWO, fears that the Navy’s long deployments will exacerbate existing readiness problems within the surface fleet, and wonders whether easing up on the operational pace last year might have prevented sailors and their vessels from premature wear and tear.

The Navy and the Pentagon “should’ve slowed things down” in 2020, Martin argued, and accepted that “there may be gaps in some theaters.”

Martin also questioned how much the presence of a gray hull really matters to America’s adversaries in combatant commands like the Middle Eastern waters of U.S. Central Command, where having a carrier on station has been a given for some time.

“The geopolitical message, that’s understandable, but it’s not real clear that either the Iranians or the Chinese or the Koreans or anyone else would have particularly noticed that there was a three-week gap in presence in some theater,” Martin said.

“How often was Stout in some place where people could see it was there?” Martin said. “Did the Iranians even know it was there?”

Martin believes this longstanding practice of pushing ships out around the world in the name of presence is “at best unproven.”

“What is proven is that the ships were kept out for an extended period of time,” he said. “What’s also pretty clear is the material condition of the ships can’t stand that.”

Readiness and a frenzied pace of operations was highlighted in Big Navy reviews following the Fitzgerald and John S. McCain collisions of 2017.

“It’s as if nobody paid attention to what was said,” he said. “They’re still scrambling to try and meet presence.”

When the Navy strains to meet commitments and doesn’t consider alternatives, it raises questions about what kind of force will be available if war were to break out, Martin said.

“Apart from what it does to families and sailors, which is big enough, what it means if something is really needed,” he said. “It’s not clear the capacity will be there.”

“What it’s likely to do is create a situation where the Navy simply is not able to meet the larger-scale conflict because it’s expended so much of its effort trying to maintain presence for the more theoretical conflicts,” Martin said.

Jan van Tol, another retired ship captain who commanded several forward-deployed warships during his career, also fears that retention and recruiting will be impacted by “continued extended deployments without any real form of R&R.”

Big Navy should consider creating something akin to “deployment pay,” which would bring “substantial extra pay” to sailors’ pockets as soon as a deployment starts and including any quarantine period.

Van Tol also said he think the Navy needs to reconsider its deployment patterns.

“Make them normally no more than three to four months, and make them ‘surprise’ deployments, which would be consistent with the (National Defense Strategy’s) notion of being ‘unpredictable’ to adversaries,” he said.

Such policy changes would likely irk the COCOMs, which might resist not having their standard carrier strike group presence, van Tol noted.

“Arguably, though, some of those gaps could be covered by genuine expeditionary strike groups” involving amphibious assault ships augmented with cruisers and destroyers “so that they really do constitute a strike group, though of course not a heavy one centered on (an aircraft carrier).”

RELATED

Pricey assets

The double pump deployments for Roosevelt and Eisenhower this winter raise questions about the Pentagon’s stewardship of some of its priciest assets. Ike is nearing the end of its hull life and experts told Defense News, a sister publication, this fall that deploying the carrier twice in one year would almost certainly require the ship to enter a prolonged and expensive shipyard availability.

TR has been in service for 34 years, the same age that Ike was during its last back-to-back deployment in 2012 and 2013. Ike’s experience back then could portend what is to come for TR after its double pump.

Those deployments in 2012 and 2013 came with enormous consequences for Eisenhower, with workers taking over two years to fix the ship during a maintenance period that was supposed to last just 14 months. When Ike deployed again in 2016, the ship was in such rough shape when it got back that it couldn’t get out of the shipyards in time for a scheduled deployment, meaning the carrier Truman had to make three deployments in just four years, including a double-pump last year.

In an email to Defense News, the Navy fleet’s deputy readiness officer said the service continues to manage the readiness challenges that forced Ike into a double pump in 2012 and 2013.

As the Navy continues to roll out its deployment system, the Optimized Fleet Response Plan, two deployments in the same 36-month readiness cycle is just the best option.

“We continue to recover readiness from the conditions that led to the introduction of OFRP in 2014,” Capt. Dave Wroe wrote to Defense News. “Specifically, over consumption of readiness, lack of budget stability, and the resulting impact to the industrial base. At six years of OFRP maturation, we are experiencing tangible improvements with manning, mission capable rates, and ship availability performance.”

Because the fleet was in such a deep readiness hole when OFRP was being implemented in 2014 and 2015, it is taking the entirety of a nine-year maintenance planning cycle to dig out, Wroe said.

And while fleet planners take the strain on an individual crew into account, “a second deployment per cycle is sometimes the best overall course of action” to spread the burden throughout the fleet and not set back the gains in readiness the fleet has made over recent years, Wroe added.

But what the history of the Nimitz-class carriers makes clear is that the double-pump deployments for Ike and Roosevelt this year won’t be without consequence.

Aircraft carriers are especially hard hit by being overused, Bryan Clark, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute, said in an interview with Defense News this fall.

“It’s hard for people outside the Navy to recognize how much of a readiness debt it is to deploy an older ship like the Eisenhower like that,” Clark said. “When you force the ship to deploy more than it was designed to deploy, especially a complicated ship like a carrier, so many things fail or get degraded that it just takes a long time to dig out of that hole.”

“And because the carriers are so large and complex, and because it’s hard to do the maintenance for them underway, the debt is very real and needs to be repaid.”

RELATED

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.