Among the many takeaways that Andrew Mauldin has gleaned in his years working as one of the Navy’s deployed resiliency counselors, one stands out: Never underestimate the little things that remind you of home, even something as simple as the soothing smell of an air freshener.

Mauldin is a civilian marriage and family therapist by trade and has embarked aboard several aircraft carriers and amphibious assault ships as a resiliency counselor.

Ship life is rough. So part of the counselor’s job is to provide crew members with a place to offload the stress that slowly builds throughout the day, like a pressure release valve. As someone who stands outside of a sailor’s chain of command, Mauldin, and those like him, provided an oasis of sorts for stressed sailors.

RELATED

Known in the Navy as DRCs for short, such counselors also provide a reminder of the non-operational world that each sailor comes from, and a heartening affirmation that life is not all drab, gray metal, Mauldin and other counselors told Navy Times earlier this year.

As such, part of that can involve the insertion of air fresheners in a counselor’s office or the adjacent “P-way.”

“It’s amazing what a non-flammable scent can do” for a wary sailor’s mindset, said Mauldin, who now supervises the resiliency counselor program from San Diego.

Some crew members just need a few minutes’ break from the relentlessness of ship life, he said, and stepping into a counselor’s brightly decorated office and catching a whiff of the air freshener, receiving a mini break in the process, can do wonders for the deployed mind.

“I used to keep candy in my office all the time,” added Miriam Lau, a licensed clinical social worker and resiliency counselor who deployed aboard the aircraft carrier Carl Vinson earlier this year and was featured among the crew on the ship’s deck during a Super Bowl national anthem montage.

“I had a couple of different people who had really high-stress positions on the ship who would come by,” she recalled. “They would call (the candy) their motivational gummy bears. They would just pop in, and it would just be a brief check-in…a moment of decompression for them, that little getaway.”

The initiative began in 2013, and 10 years after its inception, the Navy’s deployed resiliency counselor program is evolving as its counselors work to provide sailors a place to offload the kind of daily stressors that don’t require a trip to medical or to a higher level of mental health care.

RELATED

And as concerns continue to emerge about the mental health of today’s fleet, the counselors have become more embedded in the fleet, even as the program continues to grapple with a provider shortage that has reverberated across America.

Practices have changed since the program’s inception, and these days, resiliency counselors deploy with a ship and are there for the crew when the ship gets back home when the long grind of maintenance begins.

“It wasn’t always that way,” Mauldin said. “It was kind of understood that the (resiliency counselor) would jump on for the ride and then jump off when they got back to port after deployment.”

Working to keep the counselors with the ship’s force after deployment provides a continuity of care for the crew, the counselors said, and they are sometimes temporarily attached to units who need a bit more attention.

“Over the last several years, we’ve been really trying to move it to where the standard is to keep them embedded with the command through the entire lifecycle of the ships, going into the yard period but at the ship or at the (berthing barge) that’s next door,” Mauldin added.

RELATED

Still, Mauldin and other program leaders acknowledge that is not always feasible.

The resiliency counselor program has 42 billets, two for every carrier and amphib in the fleet.

As of mid-July, 18 of those positions remained unfilled, according to officials.

On the West Coast, 12 out or 16 counselor positions are filled, while 10 of 22 are filled on the East Coast, officials said. Overseas, half of the four billets are filled.

“Deployed Resiliency Counselors are incredibly effective in improving the quality of service for our service members,” Navy Installations Command spokeswoman Destiny Silbert said an email. “They provide invaluable support and counseling during what can be a challenging time for Sailors.”

The program is not alone in its struggles to fill all its open spots.

Navy leaders have spoken of the high demand for mental health professionals across the country, and that shortage of providers continues to impact the Navy’s ability to attract counselors.

An investigation last year into conditions aboard the carrier George Washington following a cluster of crew suicides found that the resiliency counselor for the ship while it was in the yards was located miles away, and few interviewed sailors even knew that such a resource was available to them.

There is also the fact that these resiliency counselors deploy with the ship, live with the sailors, and endure the same long hours that they do.

“It’s not the easiest position to fill,” said Justin Thomas, the counselor program manager for Navy Region Southwest. “The reality is we are almost asking them to become active duty, but these are civilian counselors.”

But to hear from Lau, fellow resiliency counselor Teresa Mendoza, and others, the work is particularly gratifying because of the direct impact they can have on an individual’s well-being.

That is, once they’ve figured out how to get around the ship.

“You have to have this mentality of wanting to be excited to jump in, being willing to get lost and ask for directions,” said Lau, who has also deployed aboard the amphib Essex. “You become part of the crew like that. I mean, that’s how (sailors) feel when they first get here too, I’m sure.”

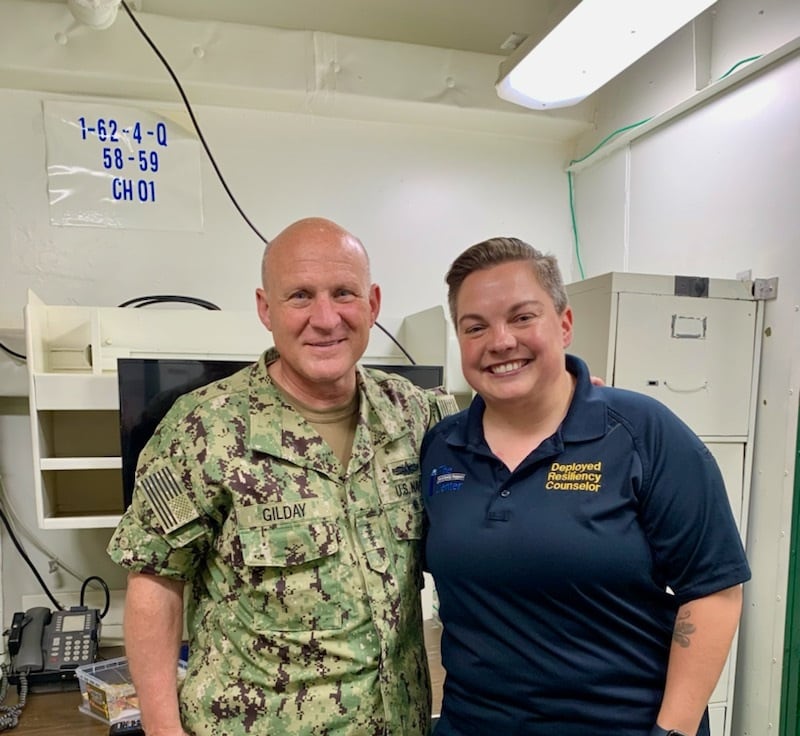

Resiliency counselors are with the crew “wherever they are,” Mendoza noted, rocking a deployed resiliency counselor polo shirt, getting to know the different divisions.

‘I’m going to be available’

Counselors like Lau and Mendoza deploy with the crew to provide “non-medical counseling,” and they do not report who visits them to the chain of command.

“Our goal is to help treat human issues, regular life stressors that we all deal with…whether it’s a one-time session because of something acute that’s just happened and they need to vent, or we can see them up to 12 sessions of short-term counseling, working on a specific goal,” Lau said. “To really, hopefully, keep them from having that mental health diagnosis and needing that higher level of ship’s medical. We’re trying to provide support at more of that preventive level.”

Mendoza said the issues they see sailors for run the gamut.

“Relationship issues, grief, death and dying, or perhaps they are trying to detach themselves from a toxic relationship,” she said.

When a sailor comes to her with suicidal ideations, Mendoza said she asks them if they really want to end their life as part of their safety assessment.

“But a lot of times, they really just want the pain to go away,” she said.

Lau said she receives a lot of visits from sailors who struggle with the 24/7 nature of deployed ship life, and the obliteration of any work-home life boundaries.

“Especially as we get into workups and start doing underways, for people who have never done that before,” she said.

If someone comes in with imminent suicidal ideation or criteria for a specific mental health diagnosis, Lau said they walk them over to the ship’s medical department for more in-depth evaluation.

“But I think most people I did counseling with on deployment… their cases were closed because they met the goals that we were working on,” she said. “Things got better. It didn’t mean it got easy; it doesn’t mean the stressor went away. But their outlook on it and how they approached the stressors, and how they regulated their emotions, those types of things got better.”

Thomas worked for a nonprofit before joining the Department of Defense, and recalled worrying about whether a patient he saw was going to have a place to sleep that night.

But a military population is in many ways more easily treatable, given their youth, health and relative stability when it comes to income and housing, Thomas said.

“These are fairly healthy people that we get to kind of help redirect sometimes, and just listen to sometimes, and get them back on track and back to work, and it’s because of the age,” Thomas said, “They can change those patterns pretty quickly.”

Being a civilian helps sailors trust the counselors onboard, and Lau said most of the sailors she sees are the E-4 rank and below, but she also has chiefs and officers drop in as needed.

“Sometimes we need someone to talk to who’s not in our chain of command or who’s not part of our support system back home,” Lau said.

Often, she added, Lau helps sailors break the cycle of negative self-talk rotating in their heads, to help them reframe their issues in a more productive way.

“It is a challenge when you don’t ever leave your workplace,” Lau said. “So just trying to help them work through those things so they don’t feel alone. I think a huge part is helping them feel connected and feel like someone cares about them.”

Counselors get their own office and share a stateroom with one or two officers, and have their choice of where they eat, which allows them more chances to interact with the crew.

The days vary during deployment, but are generally long.

Lau said she is usually at her desk by 7:30 a.m. and works until 8 p.m. or 9 p.m., juggling appointments, leadership meetings and division training sessions, while still leaving times for the drop-ins, known as the “door darkeners.”

“Just like the sailors never leave work, we don’t really leave work either when we’re underway,” she said. “You can have time off, but the reality is, if someone has an issue, they’re going to come talk to me and they’re going to ask me a question and I’m going to be available.”

Mendoza and Lau said they made friends with other providers on the ship and leaned on them for support when they endured their own deployment-related stressors.

“A common question the (resiliency counselor) will get is, ‘who does the (resiliency counselor) talk to?’” Mauldin said. “Everyone always thinks they’re the first person to ask that, but it’s a legitimate question.”

Lau said her services are most needed at the beginning of the deployment, when everyone is getting used to the new routine, and near the end, when sailors might stress about reintegrating into their families and off-ship life in general.

Thomas noted that earlier versions of the program largely involved counselors sporadically flying onto the ships.

At one point, he brought a baby doll on board to show new parents how to change the baby they were about to meet.

The counselors also lean on their own networks to ensure they reintegrate smoothly, Mauldin said.

“It’s a very unique position to be in because we’re trying to train and promote the things that we’re subject to ourselves,” he said. “It requires the humility to kind of go, ‘here’s what we all need to remember when we are all heading back,’ which sounds very different from the traditional ‘here’s what you all will be experiencing.’”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.