The golden age of baseball still shines with living heroes.

U.S. Navy World War II veteran Eddie Robinson turned 100 in December. As America’s oldest living former Major League Baseball player, he is among several dozen surviving major leaguers to serve in World War II and the Korean War.

The elite power-hitter, known as the “Big Easy,” because of his easy smile and laid-back demeanor, is also a member of military baseball’s most exclusive club: the several dozen major leaguers — mostly in their 90s — who served in World War II and the Korean War.

Other survivors include Robinson’s good friend, New York Yankees’ third bagger and retired cardiologist Dr. Bobby Brown, 96, a World War II Navy veteran who was called back up to serve as an Army surgeon in Korea. Dodgers’ pitcher Carl Erskine, 94, affectionately nicknamed “Oisk” by “Boys of Summer” author Roger Kahn, served in the Navy at the end of the war. Longtime Dodgers’ manager and Hall of Famer Tommy Lasorda, 93, who passed away Jan. 7, proudly served in the Army from 1945 to 1947.

Eighty-nine-year-old Hall of Famers Willie Mays and Whitey Herzog joined the fight to stem the tide on communism during the Korean War, when they swapped their jerseys to train in Army fatigues on U.S. bases.

Robinson, with a silver quarantine beard and the firm handshake of a rancher, has stealthily defied age. On his birthday call with the Texas Rangers, he said, “I hope to reach age 104. That’s my number.”

The Texan played for seven of the eight American League teams of his era. He made four All-Star teams and helped several ballclubs win pennants and World Series titles as a manager and a player.

Looking back, the 1948 Cleveland Indians World Series champion credits the Navy for instilling the discipline that helped him build a 65-year career in the game he loves. He was a player, coach, scout, manager and front-office exec for 16 MLB teams, and advocates for players seeking pensions today.

Baseball insiders say Robinson holds the record for standing for the most national anthems at games — but his military baseball career may be more remarkable.

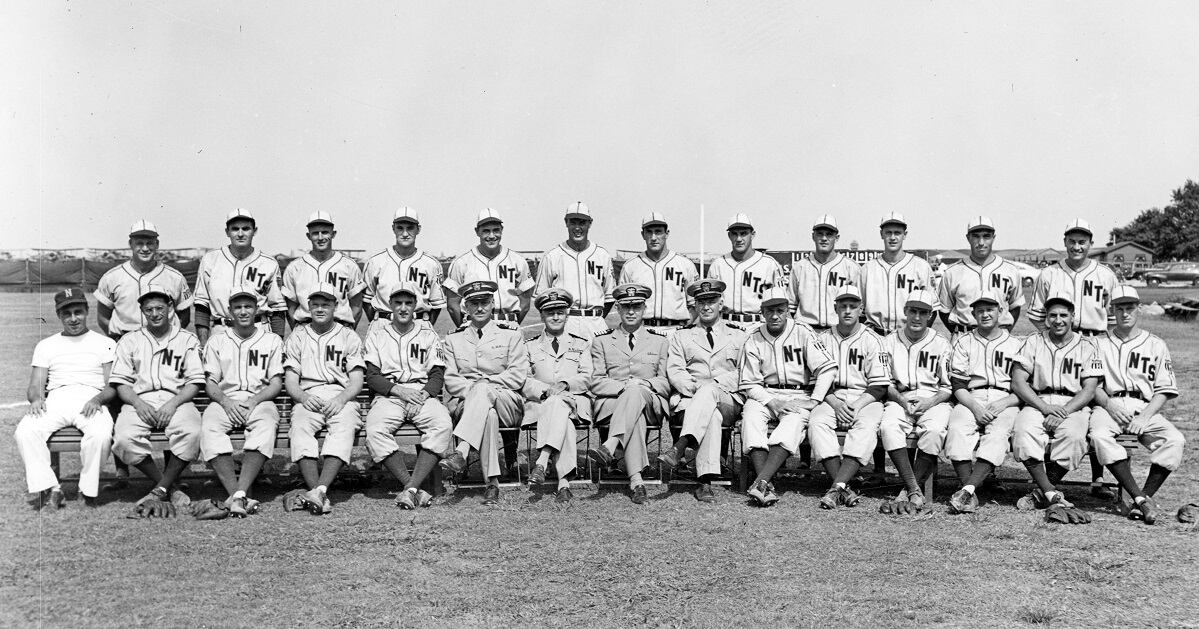

For nearly four years, Robinson served in the Navy, where he played first base for Norfolk Naval Training Station’s Bluejackets, one of the most competitive ballclubs on earth. His teammates included “Dom” DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto, and Freddy Hutchinson — and they were as good if not better than any war-time MLB team.

Today, Robinson is the sole surviving player from Norfolk’s 1943 Navy World Series, where the Bluejackets battled it out against the Airmen, a second team created down the road at Norfolk Naval Air Station. With German U-boats hunting down Allied ships along the Atlantic seaboard, the high-security, locked-down series only allowed military personnel through the gates.

Even the New York Times and Norfolk’s press corps were banned from McClure Field, where military writers and photographers captured baseball royalty in the 11-day series. The rest exists in legend.

Humble beginnings

Robinson grew up in Paris, Texas, a pastoral “Friday Night Lights” kind of town where he picked cotton as a child during the Depression. One Christmas all Santa brought him was a box of .22 shells to shoot more rabbits for dinner.

In high school, he played semi-pro ball with larger, stronger players, including a few veterans who fought in the Great War. Robinson’s first professional uniform was fashioned out of shiny red satin, when he debuted with Paris’ semi-pro Coca-Cola Bottlers. In 1939, he broke in with Class-D Valdosta Trojans of the Georgia/Florida League, the lowest rung of the minors. The rookie used his earnings to buy his mother a washing machine and worked as a fireman in the off-season as war clouds gathered in the horizon.

In 1942, Robinson got a late season call up with the Cleveland Indians, playing just eight games before he shipped into Norfolk Naval Training Station as a chief petty officer on his 22nd birthday.

“I was recruited by former world heavyweight champion boxer Gene Tunney, in the Tunney Athletic program,” he says, recalling the World War I Marine who lured pro athletes into the Navy’s athletic programs during World War II.

During the 2020 pandemic, Robinson is recording segments for his new podcast ,”The Golden Age of Baseball,” with a friend and former Marine. He talks about the old Navy stories and laughingly recalls his entry into basic training. “I was in a 60-man squad,” he says. “They marched us to the barber shop. We got our hair cut down to the skull.”

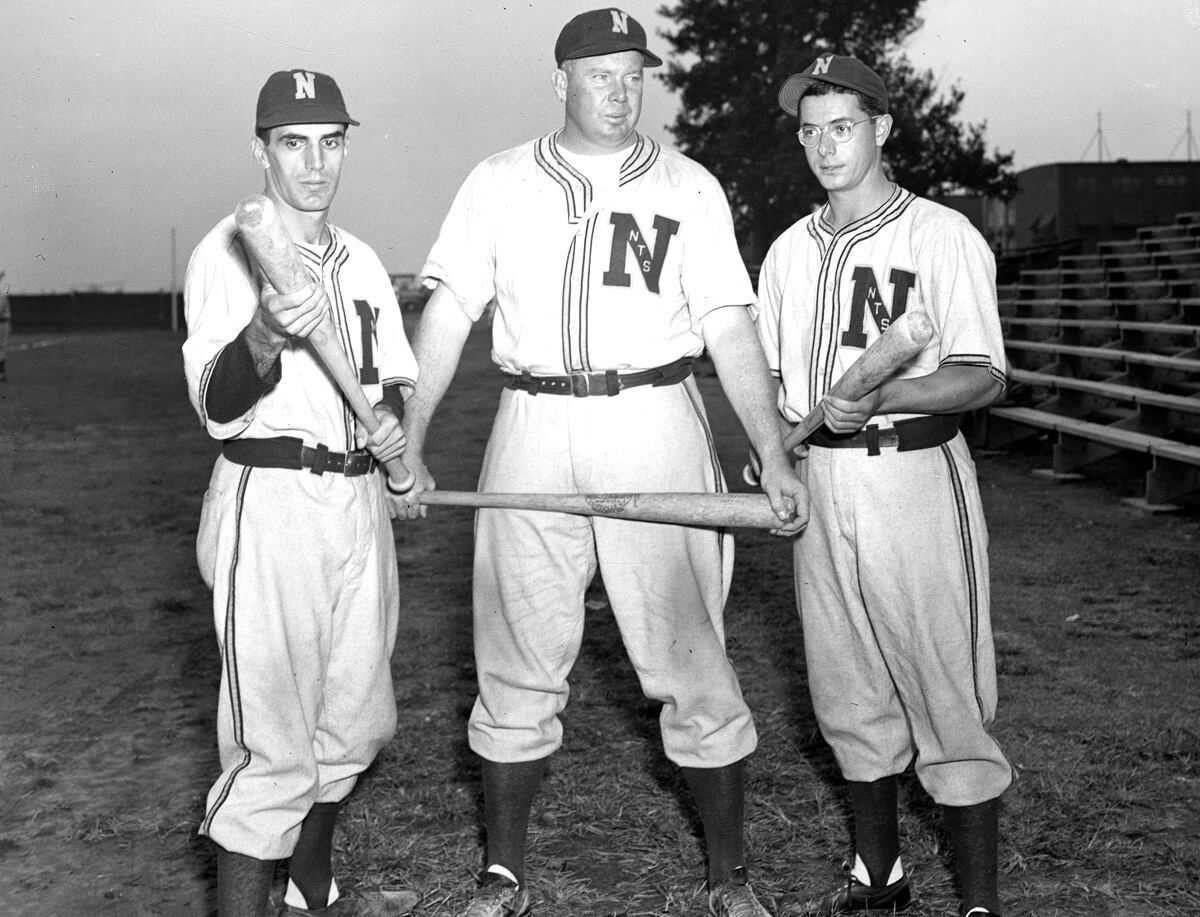

For two years, Robinson trained and worked as an athletic instructor in Norfolk, playing baseball on command for Capt. Henry McClure, a 1923 Navy Cross recipient, and Gary Bodie, a tough-as-hell manager and chief boatswain known to ship players out to sea if they didn’t perform.

In addition to greats like DiMaggio and Rizzuto, the Bluejackets roster during the war included Bob Feller, Walt Masterson, Charlie Wagner and Don Padgett.

“The Bluejackets had the best of everything. Gary didn’t spare any horses, we had two or three uniforms, the best bats, the best gloves, and padded seats in the dugout,” says Robinson, who reporters called “the loudest gun” on his squad.

In 1943, Robinson led the club with eight home runs and 79 RBIs, noted Harrington “Kit” Crissey, author of “Athletes Away” about World War II Navy baseball.

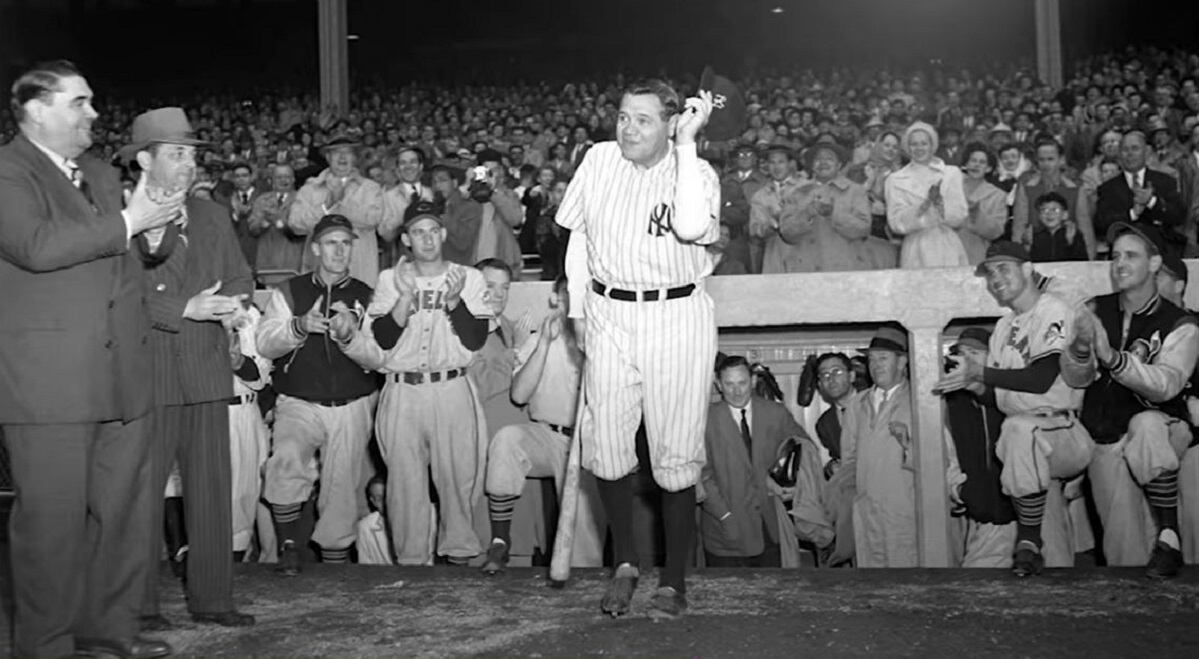

On May 24, 1943, he manned first base for the Bluejackets when they defeated the Washington Senators, 4-3, at Griffith Park, reeling in $2 million in war bond receipts. Babe Ruth rolled in for the pre-game ceremonies, dangling a cigar and wearing two-toned spats. Kate Smith sang “God Bless America,” and Bing Crosby entertained fans with “White Christmas” after Bodie reportedly kicked him out of the dugout for distracting his players.

One of Naval Training Station’s great rivalries that year was with the Cloudbusters, pilots at the Navy Pre-Flight School in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, which featured the legendary Red Sox hitter Ted Williams and his shortstop Johnny Pesky.

Traveling on “Blue Bird buses,” as Robinson recalls, the Bluejackets beat Camp Pendleton 21-0 and bested other military squads such as Fort Belvoir, Langley Field, Camp Pickett, Fort Story and Curtis Bay Coast Guard Station. The sailors defeated the Boston Red Sox 4-3 and the Washington Senators 10-5, and overpowered the Piedmont League’s Norfolk Tars and Portsmouth Cubs, Heurich Brewers, and neighboring colleges like the University of Richmond.

In September 1943, the Bluejackets faced the Airmen in a seven-game Navy World Series. The Airmen’s lineup included Hall of Famer Pee Wee Reese, Hugh Casey, Crash Davis and Eddie Shokes. Eddie Robinson banged out a two-run homer in Game 3 and the Bluejackets won, 4-3.

Shawn Hennessy, Chevrons and Diamonds military baseball historian who collects wartime memorabilia, says Naval Training Station ephemera is incredibly rare. “Sometimes players only received scorecards and programs for games like the 1945 Navy All-Star Game in Hawaii,” he said. “Equipment was also rationed.”

Over the years Hennessy found two fraying Navy jerseys, including a Pearl Harbor survivor’s USS Phoenix wool flannel. His prized possession is a 1944 William Harridge Reach official American League baseball signed by 13 of the roughly 20 Naval Training Station players, including Eddie Robinson.

In 1944, Robinson focused on antisubmarine warfare training. Still, he managed to play 88 games, where Naval Training Station took on military teams from Fort Bragg, Cherry Point, Bainbridge and Quantico, said Crissey.

That year he tied with St. Louis Browns’ outfielder “Red” McQuillen, with 11 home runs and 26 doubles, and finished the season with 99 RBIs and a .282 batting average.

In October, Robinson shipped out to Hawaii on the SS Afoundria troop ship with about 30 players including Virgil Trucks, Johnny Rigney, and Mickey Vernon, who heaved throughout the seven-day trip. He was stationed at Aiea Heights Hospital with Pee Wee Reese, Billy Herman, and Eddie Shokes, looking forward to playing ball on the islands, when his luck changed.

“In Hawaii, a bone tumor was discovered in my right leg,” he said. After multiple surgeries due to complications, and exhaustive rehab, Robinson defied the odds of medicine. In 1946, he stepped back up to the plate for spring training with a leg brace, which he tossed on the sidelines.

By 1947, the 6-foot-three, 200-pound veteran was back in MLB for good.

In July 1948, Robinson was 27 years old when he handed Babe Ruth a nicked-up Bob Feller model bat, which the Bambino used as a cane to limp onto Yankee Field for his last public appearance as fans sang “Auld Lang Syne.” Two months later, Ruth died, handing the baton to players like Robinson, who was just hitting his stride.

That fall, Robinson delivered the decisive hit in Game 6 that helped the Indians clinch the World Series title from the “Spahn and Sain and pray for rain” Boston Braves. The Tribe has not claimed a Series title since.

Robinson was admired by legends, who paused their careers to serve in uniform.

Marine combat pilot Ted Williams, who served in World War II and the Korean War called Eddie “the most underrated player of his era.” In 1952 Robinson proved the slugger’s point when he became the seventh player and the first White Sox to hit a ball over the right field roof in the 41-year history of Comiskey Park. The first six were Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmy Foxx, Hank Greenberg, Ted Williams, and Mickey Mantle.

How does one account for Robinson’s longevity? Well, late in life Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts, who served in the USAAF during World War II, remarked of Eddie, “You know, he’s never had a real job.”

Hall of Famer Branch Rickey famously said that luck is the residue of hard work and design. Robinson has always felt that he was lucky and looks forward to standing for another national anthem when baseball returns, and masks and social distancing are a thing of the past.

Anne Keene is an Austin, Texas based author of “The Cloudbuster Nine: The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win WWII.” www.annerkeene.com.