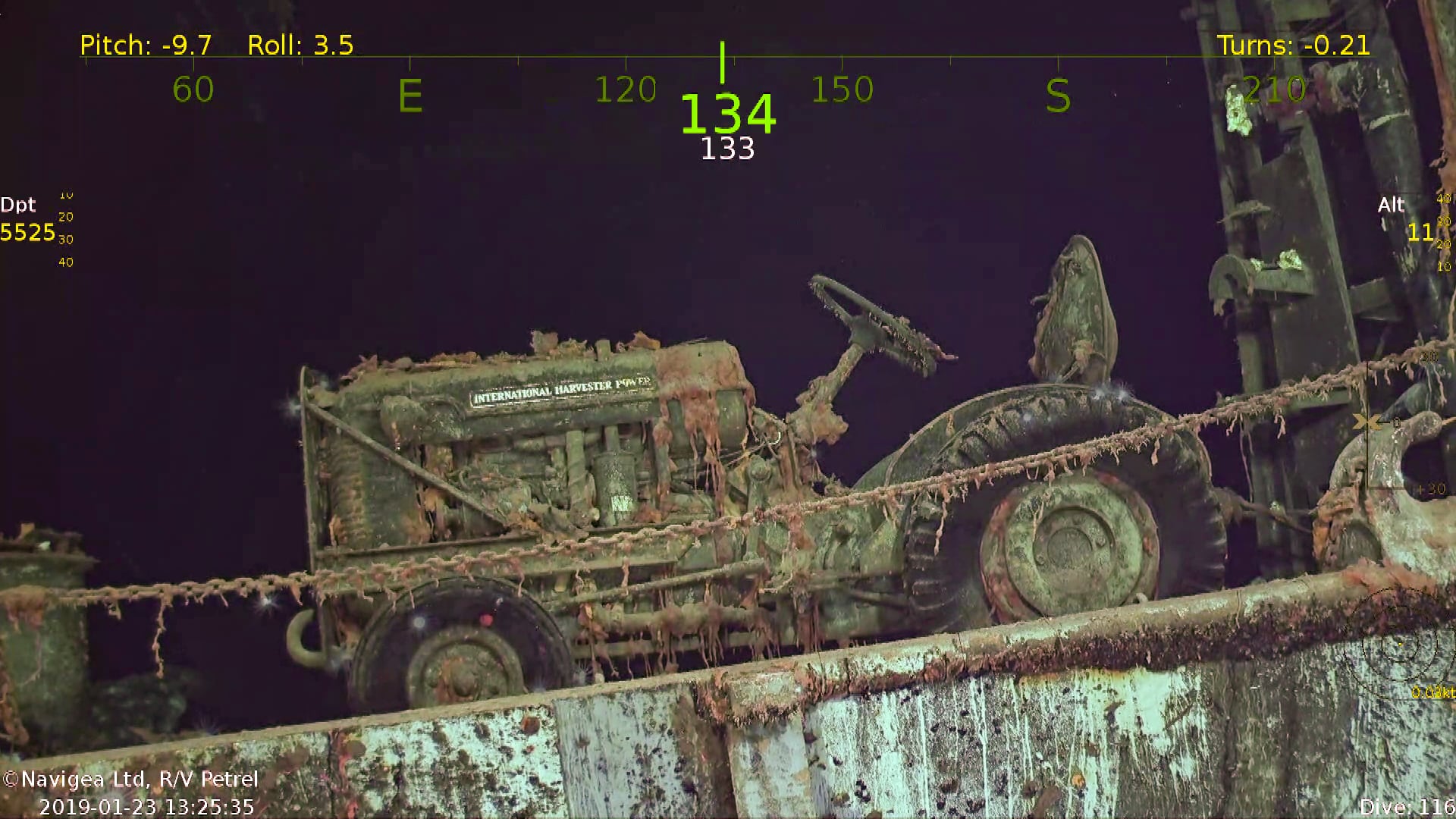

The remote controlled sub was deep into the Philippine Trench in May when the image of the wreckage flickered 20,406 feet above on board the Vulcan, Inc.'s research vessel Petrel.

The drone’s pilot, Paul Mayer, and Vulcan’s director of Subsea Operations Robert Kraft saw a funnel. Then another, both apparently sheared off a Fletcher-class destroyer, according to a video they released on Oct. 30 of the search.

Then two mangled 5-inch turrets, a propeller shaft with the screw nearby, a mast, part of a catwalk, a twist of steel skin, some horizontal deck plating, a long curve of hull painted red to show it was from below the dead ship’s waterline, a crumpled and jagged lump painted white, which means it came from inside the vessel.

From one of the funnels ran a long gouge in the seabed, suggesting something very large getting dragged off the sandy lip and into the Emden Deep, beyond where any sub can go.

Mayer and Kraft believe it’s probably the Johnston (DD-557) but it also could be the Hoel (DD-533), both of which were sunk on Oct. 25, 1944, during the brutal Battle off Samar.

Rescuers saved only 227 officers and men off both tin cans. It’s unknown how many of the 439 dead were dragged down with their ships.

What no one has ever doubted was the heroism displayed by the crews that fought and died that day on both vessels.

If the U.S. and Australian forces took the Philippines, Japan’s crucial petroleum lifeline would be cut.

U.S. ground forces began seizing several small islands in Leyte Gulf on Oct. 17, 1944. Three mornings later, A-Day, the U.S. 6th Army established a beachhead on Leyte, withstood a counterattack by the Imperial Japanese Army, and then began to push up the Leyte Valley.

American war planners didn’t realize that Japan’s Imperial Navy had concocted a plot designed to destroy the transports and supply vessels feeding the beachhead.

They formed into three major task groups. Four aircraft carriers, minus most of their planes, became the “Northern Force,” acting as a decoy to woo the U.S. 3rd Fleet north away from Leyte Gulf in hot pursuit.

If the Americans took the bait, the Japanese planned for their “Southern Force” to scoot through the Surigao Strait while a “Center Force” weaved between the islands of central Philippines before steaming down the San Bernardino Strait, to pivot in the Philippine Sea.

The surface warships then would converge on the landing areas to destroy American troops and shipping.

Navy Adm. William “Bull” Halsey nibbled, veering off eastern Luzon and leaving the San Bernardino Strait unguarded as night fell on Oct. 24, setting the Japanese operation into motion.

For two days, American aircraft and submarines savaged the Center Force, but four Japanese battleships, six heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and 11 destroyers transited the San Bernardino Strait unfettered.

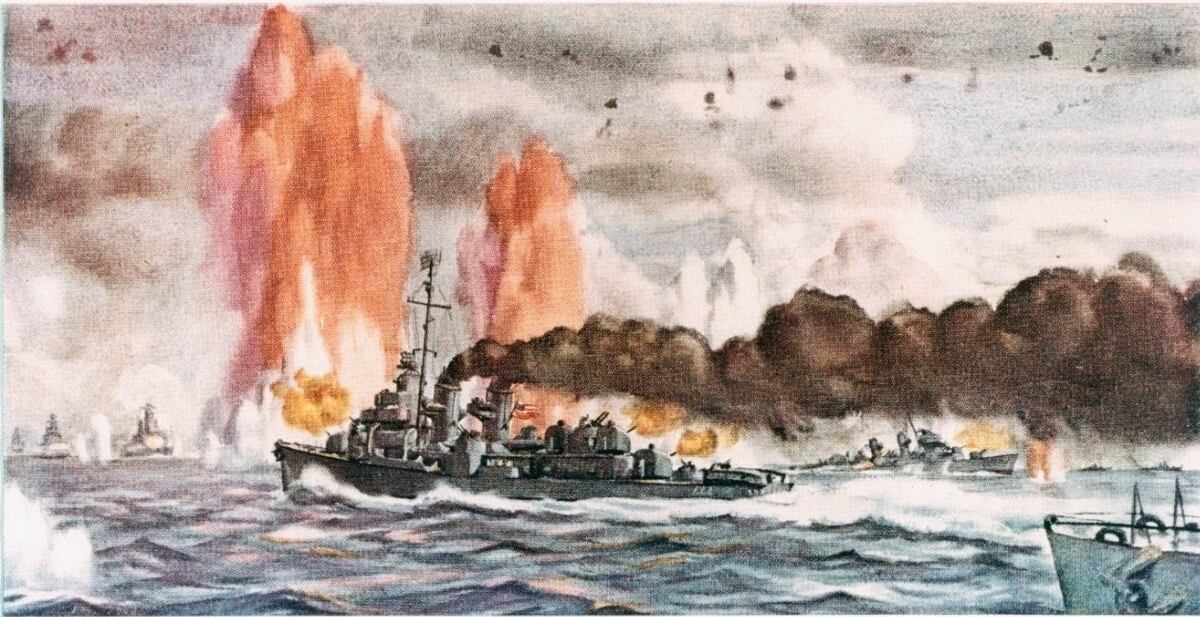

Standing between them and the fragile beachhead were six escort carriers, three destroyers and four escort ships in “Taffy 3,” the Northern Carrier Group TU 77.4.3 commanded by Rear A. Clifton A. F. Sprague.

Dawn on Oct. 25 found the destroyer Hoel’s crew beginning to chow on cinnamon rolls and beans, about 50 miles east of Samar.

Within 20 minutes, however, American anti-submarine aircraft reported receiving fire from Japanese warships. The ship’s radar began making surface contacts to the northwest.

The dim radar signatures were the surviving vessels from Central Force. Hoel went to general quarters and the crew fired the boilers to reach maximum speed.

Large shells splashed around them.

Sprague ordered the pocket carriers to launch their planes to attack the Japanese fleet and his destroyers to lay down a smoke screen to hide the flattops inside a rain squall and escape.

“We felt like little David without a slingshot," Johnston’s gunnery officer, Lt. Robert C. Hagen, later recalled in a written account now in the archives of U.S. Naval History and Heritage Command.

For 20 minutes, Taffy 3′s destroyers lay under the Japanese barrage as they steamed forward the Japanese battleships and cruisers, trying to get within range to fire their 5-inch guns and launch torpedoes.

On board Johnston, the commanding officer, Cmdr. Ernest E. Evans, gave the order to open fire.

The Johnston unleashed a barrage that damaged the nearest Japanese cruiser.

It was six times the size of Johnston. And closing.

When an enemy round splashed just short of the ship’s bow, Hagen wiped his face and quipped, “Looks like somebody’s mad at us!”

In the span of five minutes, Johnston fired 200 rounds from the 5-inch guns at the Japanese, then Evans ordered “Fire torpedoes!”

Ten zipped toward the Japanese fleet while Johnston scooted behind a smoke screen.

Exiting the bank of smoke, Johnston’s crew could see the Japanese cruiser Kumano ablaze.

The bigger Japanese warships saw Johnston. It was hit with volleys of 14-inch and 6-inch shells from a battleship and light cruiser.

“It was like a puppy being smacked by a truck. The hits resulted in the loss of all power to the steering engine, all power to the three 5-inch guns in the after part of the ship, and rendered our gyro compass useless,” Hagen later recalled.

The crew folded the destroyer back into a rainstorm and began emergency repairs to save the ship.

Hoel was struggling to navigate in the rain, fog and smoke.

Sprague ordered the destroyers to “deliver fish attack” and the destroyers tried to form into a line with Hoel in the lead and Heerman behind it.

Heerman nearly collided with Hoel, but the crew put the engines into full reverse and Hoel veered out of the way.

They then steamed toward the Japanese warships, the destroyer escort Samuel B. Roberts tagging behind them.

At the helm of Hoel, Cmdr. Leon S. Kintberger decided that the only way he could stop two columns of advancing Japanese warships was to place his destroyer between both of them.

At 10,000 meters, two of Hoel’s 5-inch shells slammed into a Japanese battleship.

Two Japanese shells then hit Hoel, knocking out all voice radio communications, the remote radar plan position indicator scope and the fire direction radar.

Kintberger was wounded, but at 9,000 meters the destroyer launched five torpedoes at a Japanese battleship.

Two more shells rocked Hoel. The engine room began to flood.

Another shell cut power to the after guns. Two more hits took out another pair of Hoel’s guns.

An explosion jammed the rudder. Hoel began a long circle back toward the battleship that was trying to kill it.

RELATED

On board Johnston, Evans realized that he had no more torpedoes and only one engine, but he thought he might be able to help Hoel and Heerman with his guns.

Chugging through the smokescreen to rejoin the sister destroyers, Johnston nearly collided with Heerman, too. Then the smoke cleared.

“At 8:20, there suddenly appeared out of the smoke a 30,000-ton Kongo-class battleship, only 7,000 yards off our port beam," Hagen later wrote.

“I took one look at the unmistakable pagoda mast, muttered, ‘I sure as hell can see that!’ and opened fire. In 40 seconds we got off 30 rounds.”

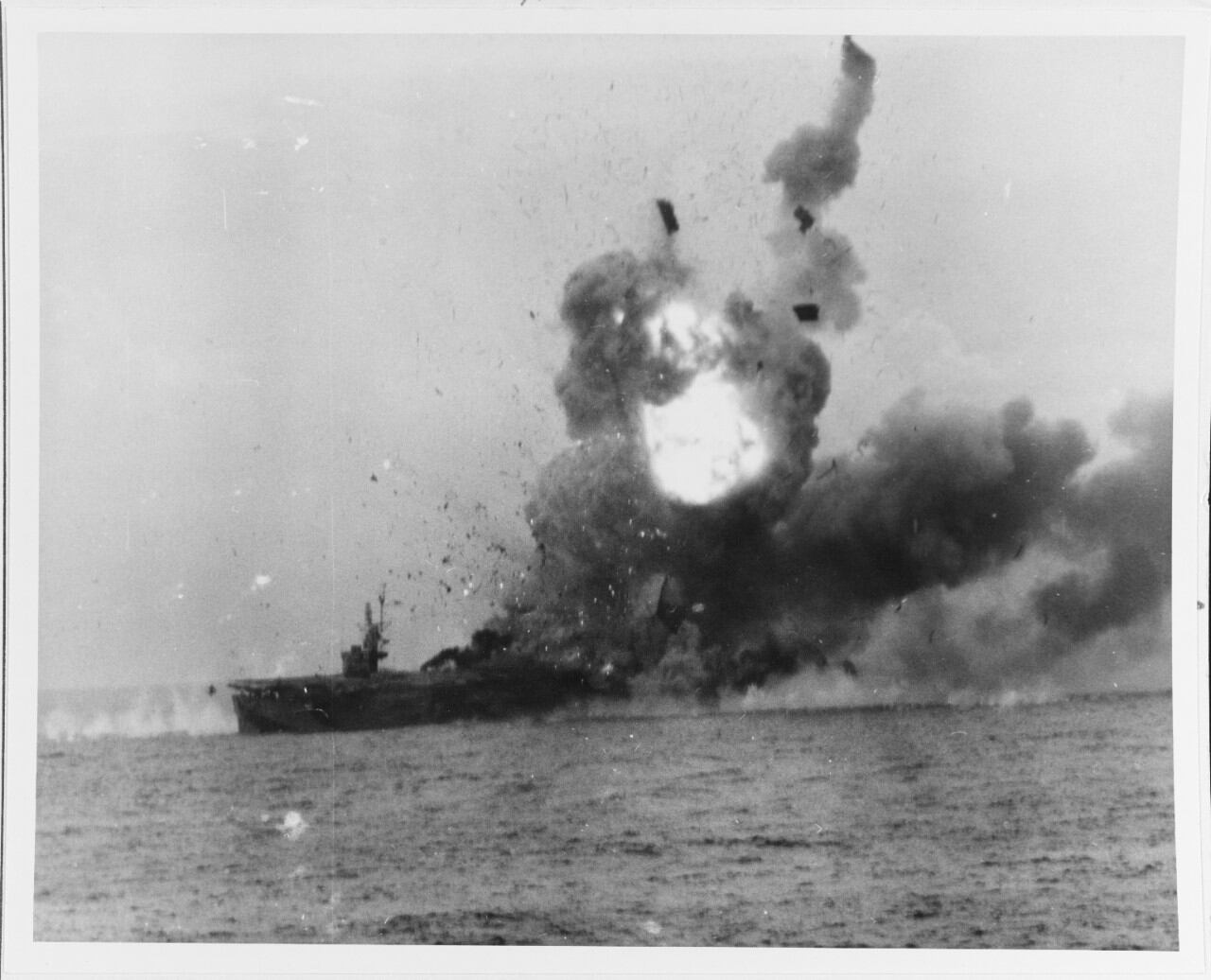

When Japanese shells began targeting the nearby escort carrier Gambier Bay, Evans ordered Johnston to draw the enemy’s fire.

Johnston pounded the Japanese warship with four direct hits. The enemy’s counter-fire mangled the bridge, forcing Evans to relocate his command to the fantail.

Shouts of “More shells! More shells!” could be heard from one of the ship’s batteries.

“We were now in a position where all the gallantry and guts in the world couldn’t save us, but we figured that help for the carrier must be on the way, and every minute’s delay might count," Hagen recollected.

“By 9:30 we were going dead in the water; even the Japanese couldn’t miss us. They made a sort of running semicircle around our ship, shooting at us like a bunch of Indians attacking a prairie schooner. Our lone engine and fire room was knocked out; we lost all power, and even the indomitable skipper knew we were finished. At 9:45 he gave the saddest order a captain can give.”

Abandon ship.

On board Hoel, Kintberger’s crew wrestled the rudder and began to control it manually.

The destroyer closed to within 6,000 meters of a lead Japanese cruiser before Kintberger ordered the launch of the last five fish.

Hoel turned at full speed to the southwest, toward Taffy 3′s carriers. But the decision to take on both columns of closing Japanese warships left the destroyer trapped between them as they fired.

As survivors later recalled, Hoel’s deck ran slick with the blood of the dead and dying.

A Japanese shell sliced into the forward engine room. The engineering spaces flooded and Hoel began listing to port.

Another hit set the forward magazine ablaze. Sea foam swirled over the fantail.

“Before the ship sank we had to send people up to those two guns and chase the men out of there and make them cease firing and get off the ship,” Lt. Maurice F. Green, later recalled.

“They did not leave the gun mounts until there was a good list on the ship and she was settling by the stern.”

At 0855, Hoel slipped under the waves.

Lt. John C. W. Dix recollected it as a poem:

“Her bow rose up. She rolled to port and plunged,/ A great loud roaring and a sucking sound. / The bridge, Gun Two, Gun One, the anchor chain, / And then the bullnose. She was gone.”

Electrician’s Mate 2nd Class Glen Foster wasn’t nearly so lyrical: “I never felt more lonesome in my life after the water settled down.”

Less than a half-hour after giving the order to ditch Johnston, the ship rolled onto its side.

One final round from a Japanese destroyer ensured it would sink. The enemy captain rendered a final salute to Johnston and its crew.

Of the 327 officers and sailors on board, only 141 would survive the battle.

Cmdr. Ernest Edwin Evans, half-Cherokee and one-quarter-Creek, became the first Native American in the Navy to receive the Medal of Honor.

His came posthumously. Although he’d been spotted in the water after Johnston capsized, rescuers never found him.

"The Johnston was a fighting ship, but he was the heart and soul of her,” Hagen said.

Hoel’s Cmdr. Kintberger received the Navy Cross for his heroism, but he nearly died.

Two days would pass before the bulk of his crew were pulled off their rafts.

By then, 252 shipmates were gone. Only 86 officers and men survived.

“Fully cognizant of the inevitable result of engaging such vastly superior forces, these men performed their assigned duties coolly and efficiently until their ship was shot from under them," Kintberger concluded in his after action report.

What the men bobbing in the water didn’t know was that the combined attacks by Taffy 3′s aircraft and surface warships forced the entire Japanese fleet to retreat.

The beachhead had been saved.

RELATED

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.