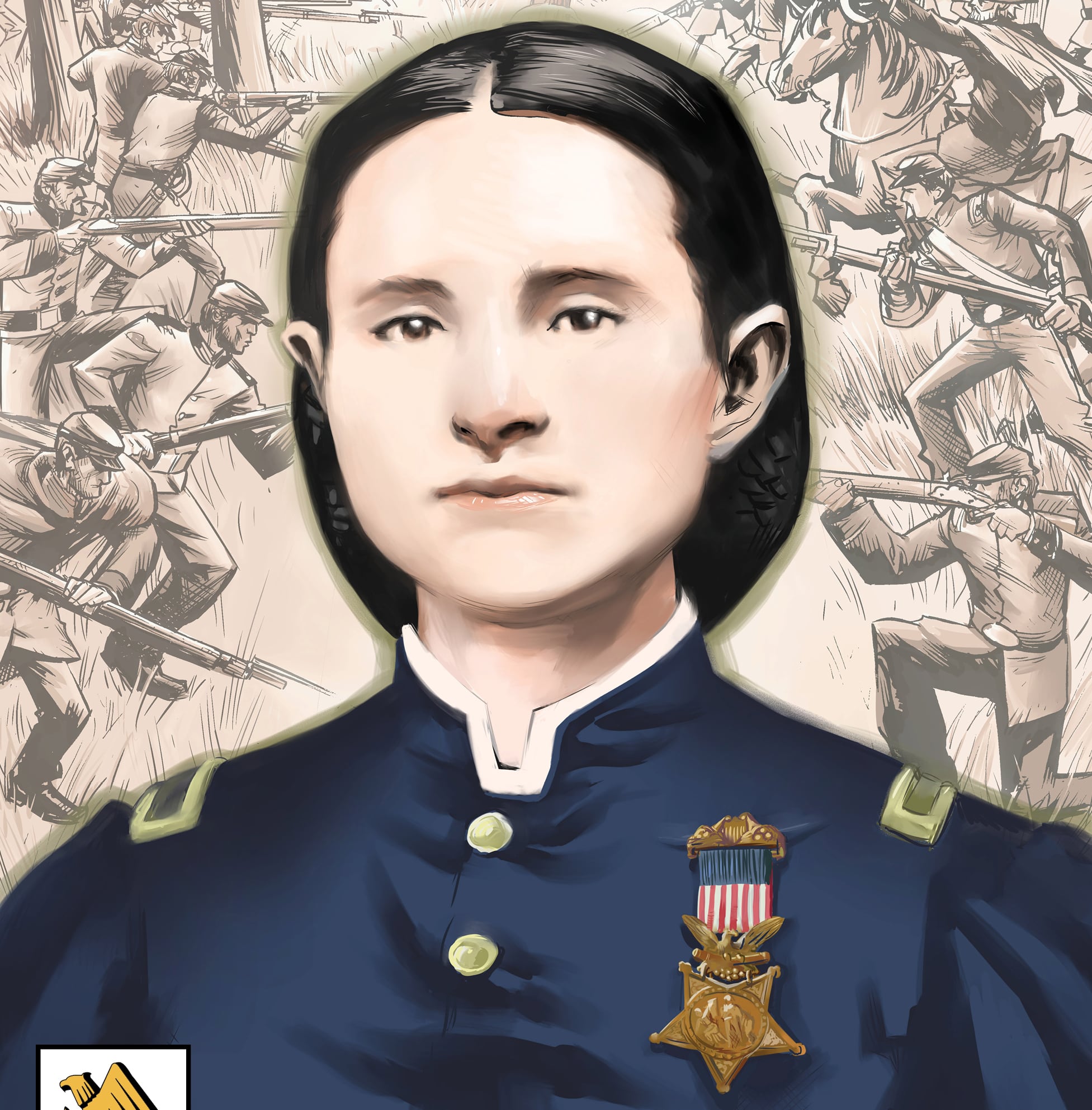

The eighth installment in an illustrated series dedicated to soldiers whose actions earned them the nation’s highest award for military valor is now available online.

The newest edition of “Medal of Honor,” a graphic series produced by the Association of the U.S. Army, spotlights the Korean War — and pre-war — heroics of Tibor Rubin, a Holocaust survivor who immigrated to the United States in 1948.

Rubin, a Hungarian Jew, was seized by Nazi forces as a teenager while attempting to flee to neutral Switzerland. Following his capture, Rubin and his family came face to face with Dr. Josef Mengele, the diabolical SS physician often called the “Angel of Death” for his practice of inhumane medical experiments on Auschwitz prisoners.

“Dr. Mengele told us to go left or right,” Rubin told the Los Angeles Times in 2005. “If you went left, you went to a gas chamber. If you went right, you went to work in a labor camp.”

Rubin’s mother and sister went left. It was the last time he would ever see them. His father, after surviving Auschwitz, would later be killed at the Buchenwald concentration camp.

Fourteen-year-old Rubin, meanwhile, was sent to Austria’s Mauthausen concentration camp, where he would cling to survival for 14 months until American soldiers freed the camp in May 1945. The impoverished teenager, eternally grateful to the American GIs for liberating a camp where more than 120,000 were murdered, vowed to join their ranks if he ever managed to make it across the Atlantic.

Three years later Rubin took the first step toward fulfilling that promise when he arrived in New York. After first working as a shoemaker and then as a butcher’s apprentice, Rubin attempted to join the Army but fell short when he failed the English test.

Undeterred, he tried again a year later in California and was accepted. An assignment to the 8th Cavalry Regiment, 1st Cavalry Division, and an immediate deployment to Korea, followed.

RELATED

Numerous members of Rubin’s outfit would later testify that rampant anti-Semitism directed at Rubin by the members of his immediate chain of command, notably by one sergeant, resulted in the young soldier, who was often called “Ted,” being thrust into more deadly assignments than anyone.

“He used to call me such bad names that I forgot my name was Tibor Rubin,” he told the Times. “He would send me to the most difficult positions so that I would be killed. It scared the hell out of me. I couldn’t even hold my rifle, but I still went.”

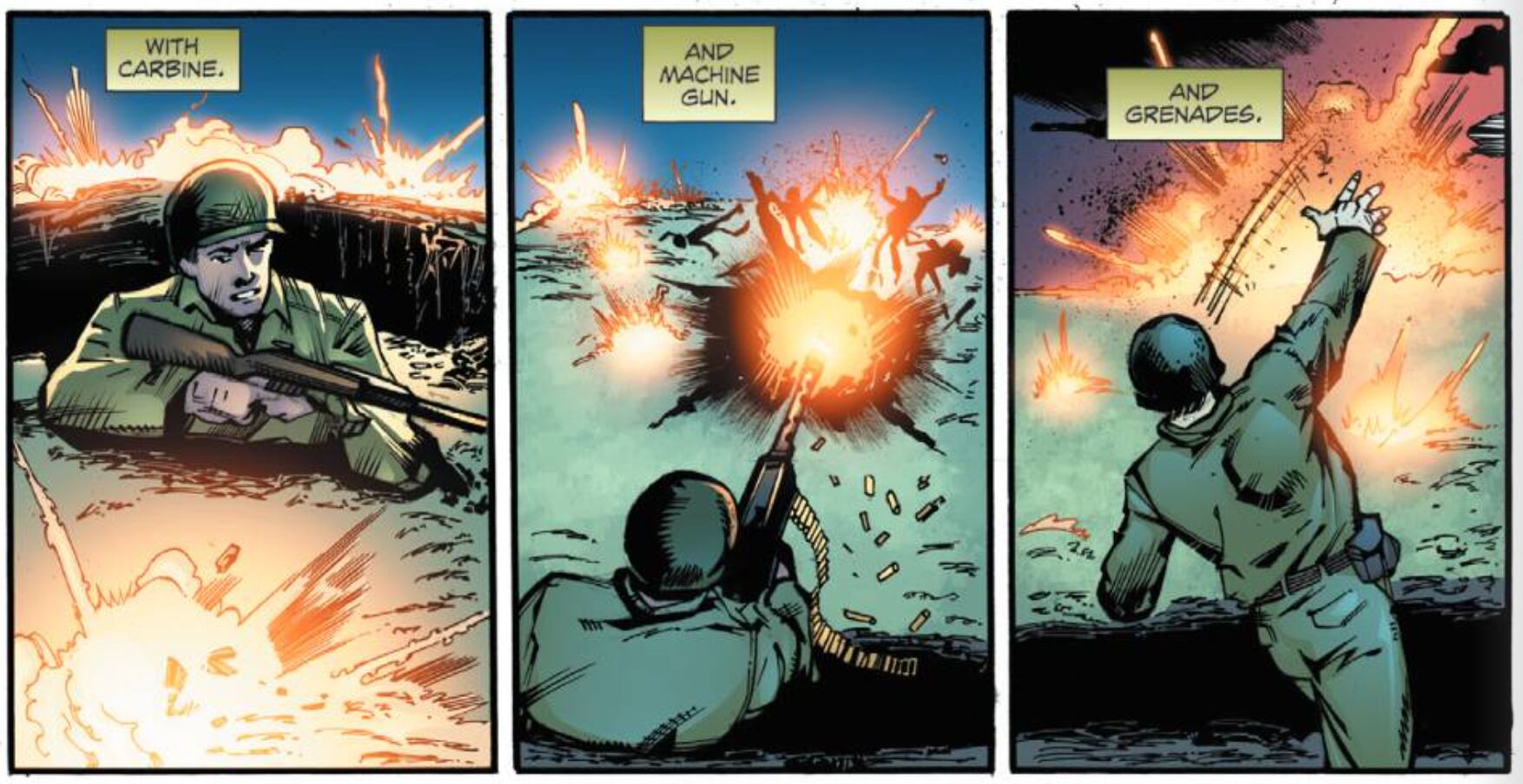

One such order came in July 1950, when, in the wake of skirmishes with communist detachments, Rubin’s outfit was attacked by a North Korean force that dwarfed the number of Americans that had up positions on a hilltop.

Outgunned, Rubin’s commanders ordered the retreat. One needed to remain behind, however, to provide cover fire.

For more than 24 hours Rubin dashed from one foxhole to another, using his rifle, a machine gun and grenades to repel the wave after wave of enemy fighters.

“The Koreans were coming up the hill. There were so many, they looked like ants,” Rubin told the Times.

“I didn’t have too much time to get scared, so I went crazy. I was like a machine, a robot. I ran around to every foxhole on the hill and started throwing hand grenades and shooting my rifle to make as much noise as possible.”

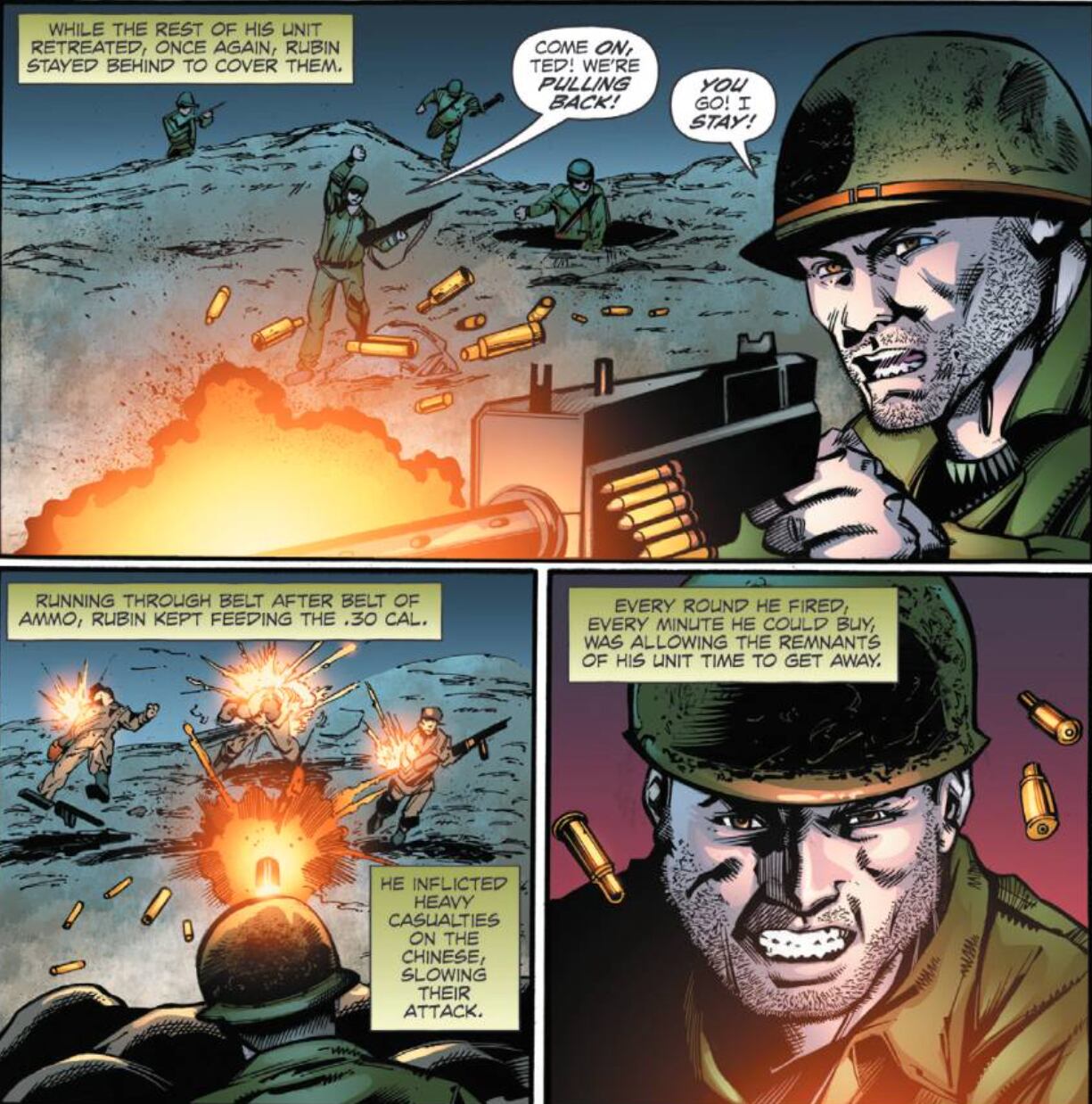

Months later, a massive assault by the Chinese had Rubin staring down death once more. When the retreat sounded, Rubin took up position on .30 caliber machine gun. For hours he expended one belt of ammunition after another. It wasn’t until the blast of a grenade peppered him with shrapnel that he was finally knocked out of the fight and taken prisoner.

Rubin would spend the next 30 months in a prison camp in North Korea, where he would risk his life almost nightly, according to fellow prisoners, to steal food from the enemy’s supply.

“If they caught me taking food, they would have shot me right on the spot,” Rubin told the Times. “I was doing what I could to keep my brothers alive.”

Fellow prisoners credited Rubin with saving the lives of at least 40 Americans who were being held captive.

Rubin was recommended multiple times for the Medal of Honor for his actions. His sergeant, however, who was given the task of filing the medal recommendation by an officer killed shortly after issuing the order, never bothered to complete the paperwork.

“I really believe, in my heart, that [the sergeant] would have jeopardized his own safety rather than assist in any way whatsoever in the awarding of the Medal of Honor to a person of Jewish descent,” Rubin’s corporal, Harold Speakman, wrote in an affidavit.

“This man did, with full knowledge of his actions, withhold the recommendations from the proper channels, therefore depriving this soldier of the medals which he so rightfully deserves.”

After being freed in a prisoner exchange in the spring of 1953, Rubin returned to California to work alongside his brother. He devoted countless hours over the remainder of his life to volunteering with and assisting local veterans.

Fifty-five years would pass before Rubin was finally given his appropriate recognition, when President George W. Bush presented him with the Medal of Honor at a White House ceremony.

“Those who served with Ted speak of him as a soldier who gladly risked his own life for others,” Bush told a small crowd that included Rubin’s wife and two children.

Rubin died on Dec. 5, 2015, at his home in California. The 86-year-old remained proud of his service to his adopted country up until his final days.

“It’s a wonderful, beautiful country,” he said years earlier at the White House. “We are all very lucky.”

Rubin’s heroics made him a clear-cut selection for the AUSA team’s fourth graphic novel installment of 2020.

“One of the things I was really impressed with is the level of work that the creative team has put into it,” said Joseph Craig, director of AUSA’s book program.

“The scripts and the artists — these are all people from the world of professional comic book publishing. These guys know comics, they know military comics in particular, and the job is just really top notch.”

The collaborative team included script-writing by Chuck Dixon (“Batman,” “The Punisher”), cover work and finishes by Rick Magyar (“Avengers,” “Captain America”) , color work by Peter Pantazis (“Black Panther,” “Superman,” “Wolverine”), and lettering by Troy Peteri (“Spiderman,” “Iron Man,” “X-Men”).

Past issues have highlighted the actions of figures such as Alvin York, Henry Johnson, Roy Benavidez, Daniel Inouye, Audie Murphy and Sal Giunta.

Read the full issue of “Medal of Honor: Tibor Rubin” here.

J.D. Simkins is the executive editor of Military Times and Defense News, and a Marine Corps veteran of the Iraq War.

Tags:

tibor rubintibor rubin medal of honorKorean War medal of honor8th cavalry regiment1st cavalry divisionmauthausen concentration campausa graphic novelausa medal of honorTibor Rubin koreaIn Other News