Across the entire force, only two sailors reportedly had their warfare pins tacked onto their flesh in the past year — one of the many signs that Navy officials have turned a corner in their fight against hazing. of the many It's all fun and games until someone gets hurt, they say.

The dangerous or demeaning initiation rites and verbal dressings-down that have been part and parcel of military life are steadily becoming a thing of the past, according to the Navy officials who oversee the effort to stamp out hazing. But many veterans and current sailors question whether the service has gone too soft.

The Navy is a professional organization and sailors are expected to uphold that standards, said the leader of the Navy's anti-hazing effort. 21st Century Sailor office,

"I think all of us want an environment that encourages fun, because it should also be fun to come to work," said Capt. Star Hardison, the acting head of the 21st Century Sailor office, told Navy Times in a June 30 phone interview. "But at the same time we need to manage that by maintaining a level of dignity and respect."

The 21st Century Sailor office took in 4837 complaints of hazing from April 2014 to June 2015, of which 28 were confirmed as hazing, according to official data compiled by their office. The findings on four cases are still pending. data provided to Navy Times, The numbers have held largely held holding mostly steady since the office stood up its hazing task force in 2013. The latest tally features fewer incidents involving violence, but hazing remains underreported and is still defended in many quarters of the service.

The reports run the gamut from practical jokes to physical assault and rituals like tacking on submarine warfare devices and "good-humored restraint," as the Navy describes it, as a division send-off.

When you think of hazing, you probably think of those cultural rituals, like throwing a chief-select overboard or a punch in the crows after you make petty officer.

But the Merriam-Webster dictionary defines hazing as the practice of playing unpleasant tricks on someone or forcing someone to do unpleasant things, and that's where the Navy makes it's distinction.

"Each incident is judged by what the victim reports as it relates to hazing, and it's determined whether that sailor was exposed to any activity which is cruel, abusive, humiliating, oppressive, demeaning or harmful," said Lt. Joe Keiley, a spokesman for the chief of naval personnel's office.

That can also includes verbal abuse, which played a part in seven of the past year's complaints. Five of them were found to be hazing.

Some Navy Times readers who responded to a call-out for opinions on hazing thought that political correctness and sensitivity were broadening expanding the definition of hazing, but Hardison said it's better to be safe than sorry — sailors should report anything that gives them pause.

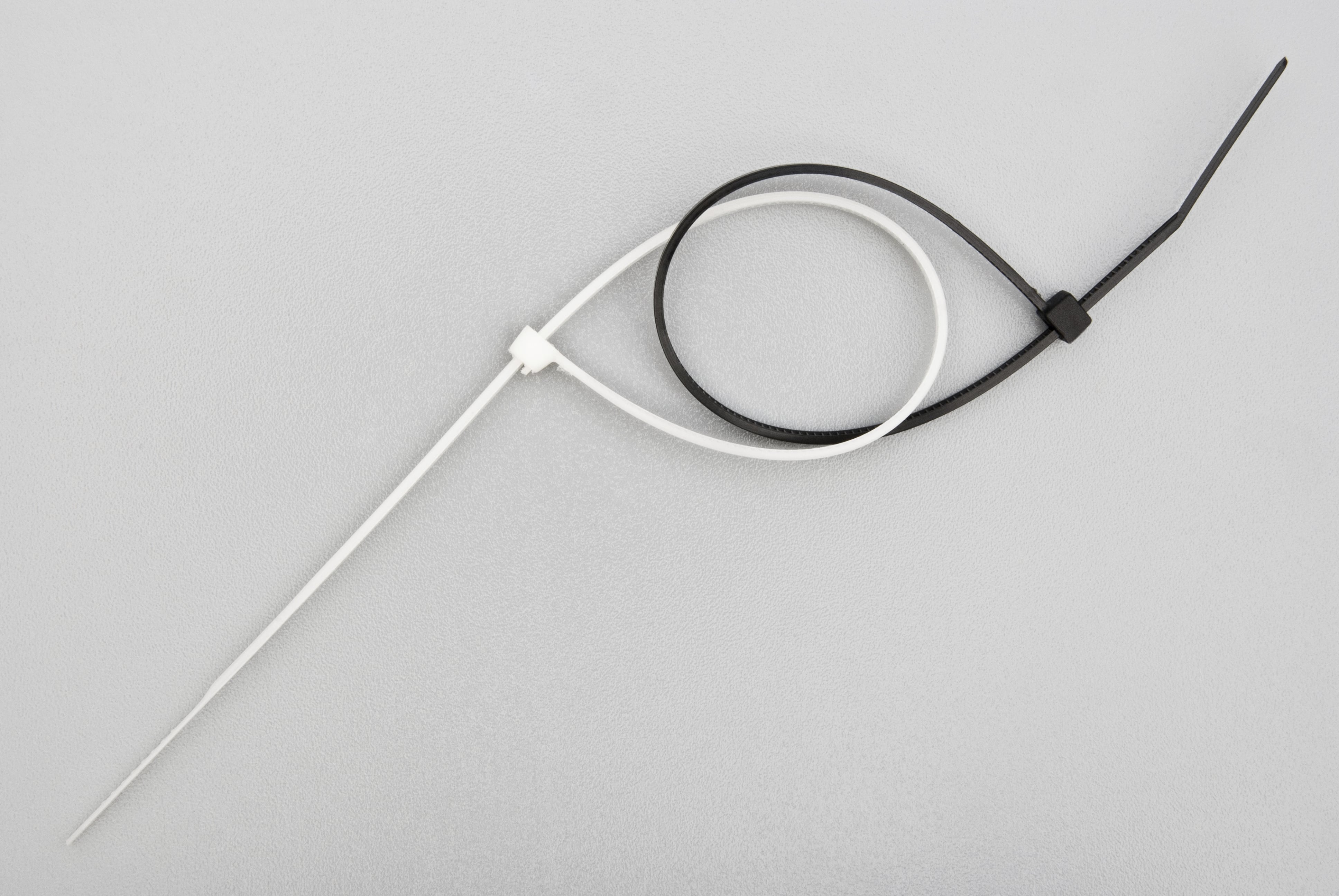

One sailor was reportedly hazed by having his hands and feet bound with zip ties, while another tied was placed loosely around his neck.

Photo Credit: Getty Images/iStockphoto

"I think it's important that any time our sailors see anything that they think isn't right, that they should always step up and step in, whether it be a situation of hazing or a safety violation," said Hardison, whose office oversees policy for anti-hazing training and policy.

The victim's perception is key in making the decision, said Keiley, but that's not the only factor. Being a willing participant doesn't mean that you weren't hazed.

For example, a February 2015 complaint alleged that an E-1 was taped to a bed by a fellow student, with consent. An E-3 reported the incident, in line with the Navy's definition of a hazing event.

"I think sailors realize that there's a time and a place for horseplay — it's probably not in the workplace," Hardison said. "I think that's coming through loud and clear through our training."

The training focuses on not only on what hazing is, but what to do about it when you see it. Numbers of reports have held steady for the past three years, but Hardison confirmed that her office believes it's closing the gap between number hazing incidents occurring and the number that are reported.

"I think that's a fair assessment," she said. "Sailors know what hazing is or isn't, and they're willing to come forward and report it, and they trust that their chain of command is going to take action to investigate."

'Combating tradition'

The flip side of the hazing debate, for many, is the dearly held rites of passage that many see as essential to their experience as sailors.

"Had my fellow submariners not tacked my dolphins to my chest, I am sure I would have felt they did not respect me and feel that I was their equal," wrote former Machinist's Mate 1st Class (SS) James Glass.

That ritual is barredheavily discouraged now, but the Navy receives complaints about it every year.

Others have strong feelings about the Crossing the Line ceremonies, typically marked by a day where wogs are initiated into the order of the shellback during a dayof nastiness, which nonetheless has been greatly toned down in recent years to address concerns about abuse and degradation.

"Back in the day, when a ship would do the Crossing the Line ceremony, sailors would be hazed to get rid of being a 'wog' and become a 'shellback,'" said former undesignated airman Roberto Lerma.

"Nowadays you can't even have fun in berthing a without someone getting mad and reporting you that you hazed them."

Though new sailors are now coming up in a Navy with a different attitude toward those traditions, some currently serving don't like the changes.

"In my view, they are combating things that are 'traditions' in the Navy," said an active-duty HM2, who asked not to be named due to concerns about his career.

"Everything is so politically correct these days that it opens doors for those who probably shouldn't make it through boot camp to complain about something as pathetic as an recruit division commander scaring someone too much or embarrassing the individual, and then that person is relieved of [his] job," he added.

The Navy is pandering to over-sensitivity, he said. Others agreed the service has been too sensitive.

"I think the Navy has lost some of its collective soul in the rush to be 'politically correct' and to make sure nobody's feelings get hurt, no matter how slightly," said former Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class (SS) Skip Kirkwood. "If a sailor can't take a little ribbing, and give as good as he or she gets, how can shipmates know that they can count on them in a pinch?"

A female sailor was told to suck on a pacifier at work, which she did. The Navy is trying to stamp out demeaning behavior.

Photo Credit: Getty Images

But others see the good in cracking down. A good-natured prank can go too far, one retired chief said.

"The problem with hazing is it can sometimes escalate if just one of the participants has a sadistic disposition," said retired Chief Boatswain's Mate Shawn Kelley. "When this happens, a pack mentality can manifest."

Kelley said he was proud to have survived his alcohol-fueled, borderline-sadistic chief initiation, but that he "would not wish that experience on anyone today."

"My instincts tell me that just as there's been an awakening in society concerning women's equality, racial equality and homosexual rights, there has also been a large upswing in awareness and quasi-universal comprehension of the wrongness of bad behavior in the world we live in, and even more so in the Navy because of the detrimental consequences to the careers of those who participate and also those who observe without reporting or trying to stop an escalation," he added.

Past Navy training has focused on what-not-to-do's, Hardison said, but her office is working on the 2016 roll-out of a new initiative called Chart the Course, which covers sexual assault, substance abuse and other misconduct issues.

"It will take a little bit of a different direction than [Bystander Intervention to the Fleet]," she said, "focusing on, what does right behavior look like and how to we emulate that?"

Meghann Myers is the Pentagon bureau chief at Military Times. She covers operations, policy, personnel, leadership and other issues affecting service members.