This article first appeared on The War Horse, an award-winning nonprofit news organization educating the public on military service. Subscribe to its newsletter.

Go Navy Tax Services seemed like a great option for sailors looking for help during tax season. Situated just outside the gates of Naval Base San Diego, one of the country’s biggest Navy bases, it was local, it was convenient, it was specifically focused on helping Navy members with their taxes — and best of all, it was free.

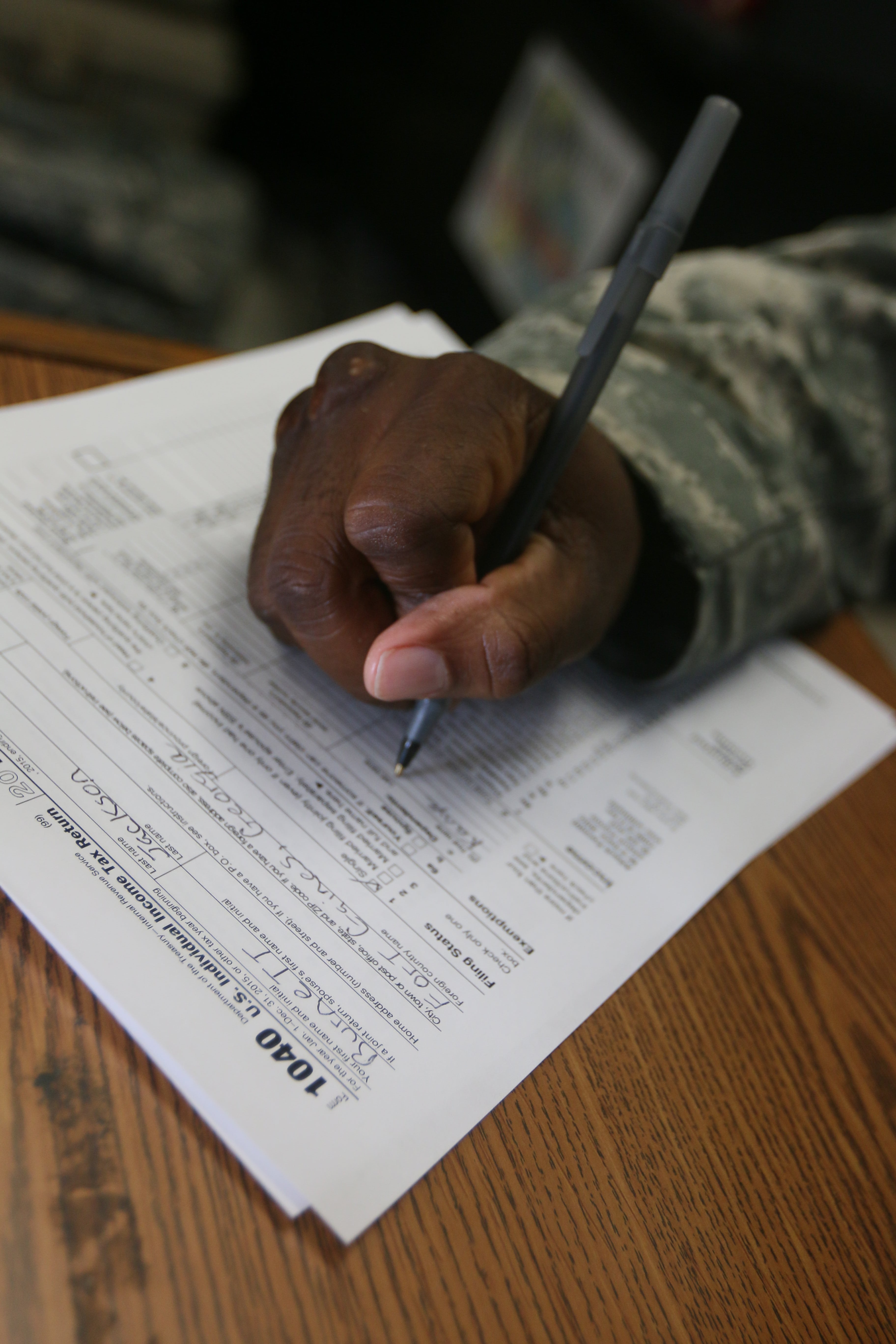

When sailors entered the doors of the Navy-flag adorned trailer where Go Navy Tax Services was based, they found what they came for: free tax preparation. But the accountants also pushed service members to open retirement accounts. For years, Paul Flanagan and his associates at Go Navy Tax Services convinced service members who came in for tax help to open various savings accounts, providing them with all the necessary forms. They just had to fill in their personal information and sign on the dotted line.

But the nearly 5,000 applications that sailors and Marines signed didn’t actually open retirement accounts. Instead, they bought unnecessary life insurance policies — without the sailors’ knowledge — and authorized withdrawals to pay for them from the sailors’ bank accounts. In turn, Flanagan and his co-conspirators earned more than $2 million in commissions on the “sales” over nearly a decade. The service members who had signed the forms lost a combined $4.8 million.

“Service members have given so much to our country,” Xavier Becerra, then the California attorney general, said in a statement after Flanagan and his associates were indicted on 69 counts of conspiracy to commit fraud, forgery, identity theft, and grand theft, among other things, in 2019. “They should not have to worry about being targeted and taken advantage of by malicious scammers.”

But service members do have to worry about being targeted by scammers — perhaps even more than their civilian counterparts do. Service members, veterans, and their families are more likely to be targeted by scammers than civilians, according to research conducted by AARP. They’re also more likely to lose money in scams. A steady income and military benefits, a soft spot for helping those who serve and those in need, frequent moves and deployments, and a unique culture that scammers can tap into to gain unwarranted trust make military members and families particular targets of scammers.

“Scammers know that veterans have access to the different benefits,” says Troy Broussard, an Army veteran who runs AARP’s Veterans and Military Families Initiative. “They know about this sense of mission. So that opens [veterans] up to be targets.”

But while scammers prey on patriotism and the trust people place in members of the military, simple steps — like knowing how and why scammers operate the way they do — can help military families put up effective lines of defense.

“We want to make sure that we arm our veterans and their families with tools to fight back,” Broussard says.

‘You have to totally be on your game’

If it feels as if your voicemail is flooded with messages asking about your car’s extended warranty or telling you the IRS has been trying to reach you, you’re not alone. Scams — deceptions intended to steal someone’s personal information or money — have proliferated in recent years, as private information has migrated online, and social media and technology have made it simple to quickly reach huge numbers of people. The increase of misinformation during the Covid-19 pandemic has only made things worse.

“There’s no way to put the genie back in the box, as far as I can see,” says Linda Sherry, director of national priorities at Consumer Action, a national consumer advocacy group. “Unfortunately, it’s just everywhere you turn. You have to be totally on your game.”

Americans lost a whopping $5.8 billion to fraud and scams last year, according to the Federal Trade Commission. That’s up from around $3.3 billion lost in 2020. About a quarter of those losses were through social media, where scammers can easily hide behind fake personas or accounts and make quick contact with millions of people.

But while the growth in robocalls, phishing emails, and social media scams affects everyone, those in the military community — active-duty members, military families, and veterans — are particularly vulnerable to targeting by scammers.

In 2020, the Federal Trade Commission received more than 200,000 complaints about scams and frauds from the military community. The amount of money lost is growing at a faster rate than the general population: In 2021, $267 million was lost, well over double the $105 million military families lost to scams in 2020. AARP found that military families are almost 40% more likely to lose money to scammers than civilians — and that when they do fall for scams, they lose more money.

Those cons range from fraudulent business opportunities and fake investments to bogus charities and sweepstakes scams. Just last month, the FTC sued Harris Jewelry, whose stores are fixtures in military communities, for falsely telling military customers their purchases would help raise their credit scores and for adding expensive protection plans to customers’ purchases without their consent.

Last year, the FTC refunded nearly $30 million to people who had been duped into enrolling at various for-profit colleges by companies that, among other things, posed as military recruiters and advertised the schools as being recommended by the military.

Another high-profile scam targeting veterans offered a “‘proven’ 21-step system” to making money from home that conned people into paying progressively more to make their way through the “system.” Red, white, and blue banners promised veterans and other “patriots” they would “Discover how a war veteran uncovered the secret to earning up to $3,300/day from his sweat-box living quarters in Afghanistan.”

But many other scams are lower profile, coming in as a phone call that offers help navigating VA benefits or a phishing email offering discount medical equipment.

“The opportunities for scams, when we went online … just exploded,” Sherry says. “[If] a scammer approaches [someone] in the way that they’re vulnerable, they will probably fall for it.”

‘They discourage donations to real veterans’ charities’

For members of the military community, those vulnerabilities come from facts and assumptions about military and veteran life — which scammers can exploit. For instance, military-focused charities are often favorites for those who have served. Giving money to these charities appeals to veterans’ sense of patriotism and service, and keeps them connected to their brothers- and sisters-in-arms.

“When we’re done with our military life, we want to try to find that second mission,” Broussard says.

But sham veterans charities abound. In 2019, the American Veterans Foundation, which promised to support homeless veterans and send care packages to deployed troops, was charged with spending over 92% of the more than $6.5 million it raised on overhead costs and hiring telemarketers — to solicit more donations.

That same year, another organization, operating under a slew of names, like Veterans of America, Vehicles for Veterans LLC, Saving Our Soldiers, and Act of Valor, was charged with soliciting donated cars and boats in support of veterans — the man behind the scam instead sold them for himself. The year before, in a coordinated effort to target sham veteran charities, the FTC and state attorneys generals took more than 100 actions against fake charities with names like Operation Troop Aid, Healing Heroes Network, Focus on Veterans, and National Vietnam Veterans Foundation.

“Not only do fraudulent charities steal money from patriotic Americans, they also discourage contributors from donating to real Veterans’ charities,” Peter O’Rourke, former acting secretary for Veterans Affairs, said in a statement announcing the operation.

Appeals for these and other fraudulent operations tend to be particularly effective when the scammers behind them can forge a personal connection with their targets. People soliciting money or information will often use military-specific jargon or technical terms to falsely signal they’re members of the same tribe.

“When you’re in the military, we all went through the same thing,” Broussard says. “When you’re connected [with someone with a similar background], at that point, your guard’s down a little bit.”

Dropping terms like “DD-214″ or military ranks helps scammers gain trust, and their knowledge of things like the stress of deployment or frequent moves means scammers can easily time and target their ploys.

“Military consumers have a steady income,” Sherry says. “They have money. They move frequently.”

They also have worries and disruptions that civilian families do not. And, when they leave the service, they may have VA and other benefits. All of this creates a perfect storm: income for the taking, and myriad ways for scammers to take it.

In some of the typical scams that target the military community, scammers may offer assistance with navigating benefits — an easy gateway to identity theft, experts say. They can direct service members with educational benefits to for-profit schools with little educational return. Recently separated veterans can be inundated with sham offers to help kickstart a business; combat vets receive offers of free medical equipment. Families at home can fall prey to worries about a deployed loved one and give up personal or financial information to someone posing as a commanding officer.

But when it comes to guarding against scammers, a little goes a long way, Broussard and others say. They offered easy steps people can take to keep themselves safe, including:

- registering with the National Do Not Call Registry

- installing robocall blocking programs

- keeping antivirus software up to date

- having a password manager to secure personal information.

Additionally, active-duty servicemembers are eligible for free credit monitoring, which can help monitor for identity theft.

Broussard also recommends having what he calls a “No Script” — a prepared line or two to end a suspicious phone call.

“If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is,” he says.

If you’re confused about why you’re getting a call, it’s always best to hang up and do your own research, Sherry says. Reaching back out to an organization to see if they actually contacted you is always a good idea before giving out any information.

“We tell people just take a deep breath, disengage, and follow up through a completely independent channel,” she says.

Keeping abreast of recent scams is also helpful since certain schemes tend to ebb and flow in popularity. Broussard points people to AARP’s Veterans Fraud Center, where military members can enter their zip code to see the most common scams. The FTC’s Military Consumer Protection page also provides service members with useful information.

“Scammers always want to find the path of least resistance,” Broussard says. “Just always know that you’re in control.”

This War Horse feature was reported by Sonner Kehrt, edited by Kelly Kennedy, fact-checked by Ben Kalin, and copy-edited by Mitchell Hansen-Dewar. Headlines are by Abbie Bennett.

Sonner Kehrt is an investigative reporter at The War Horse, where she covers the military and climate change, misinformation, and gender. Her work has been featured in The New York Times, WIRED magazine, Inside Climate News, The Verge, and other publications.