After the call, after the casualty assistance officer’s visit and after the TV news interviews, the memorial service at Arlington National Cemetery and periodic updates from the Navy, Darrold Martin found himself face to face with Lt. j.g. Sarah Coppock.

The junior officer was court-martialed in Washington last month for her role in the destroyer Fitzgerald’s collision last summer that killed seven sailors, including Martin’s son, Personnel Specialist 1st Class Xavier Martin.

Martin had just watched Coppock plead guilty to dereliction of duty. She oversaw navigating the ship at 1:30 a.m. on June 17, 2017, when the larger ACX Crystal plowed into the Fitzgerald ’s right side.

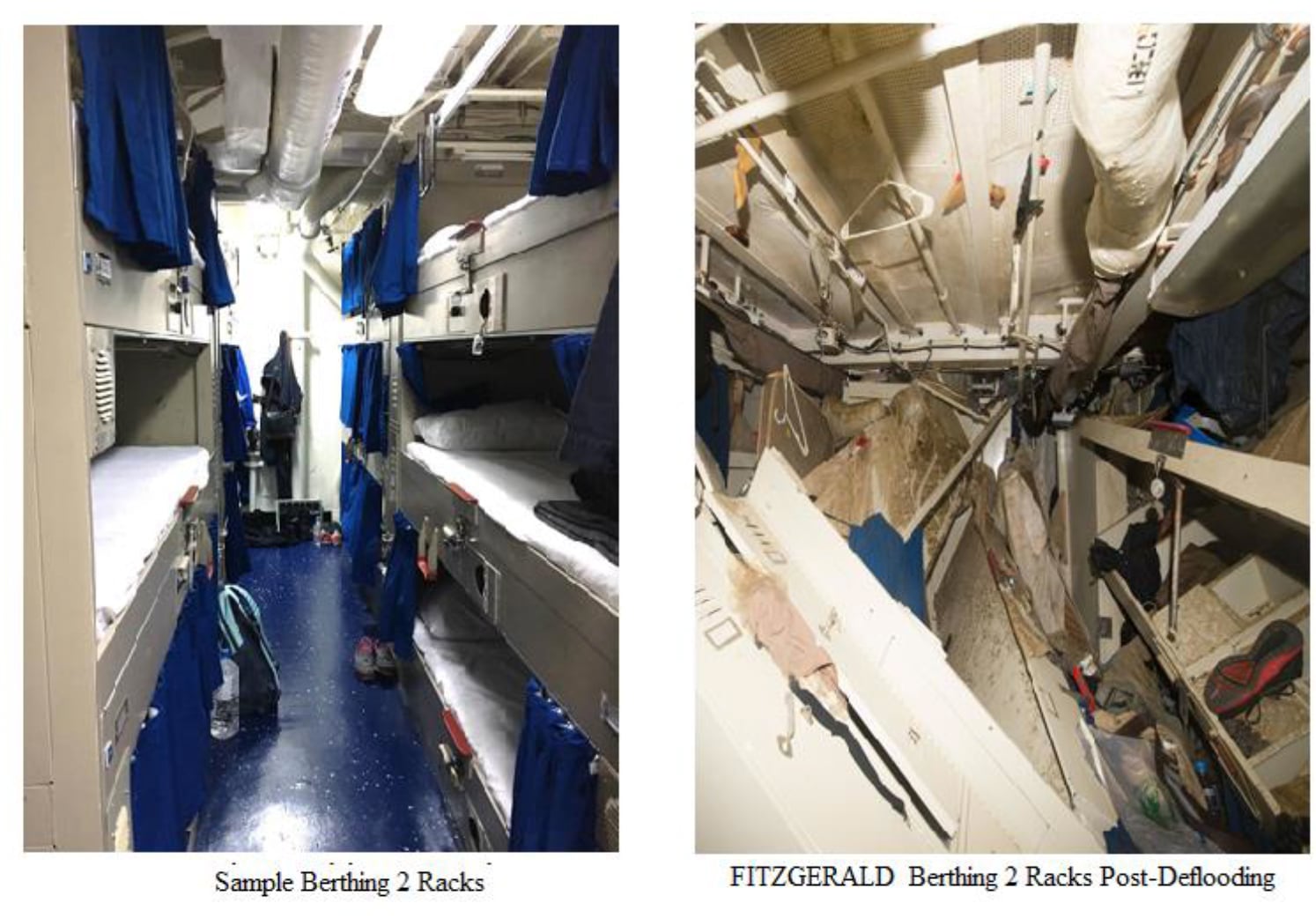

The Crystal gouged the Fitzgerald and flooded a living area beneath the water, snuffing out the life of Martin’s 24-year-old, the single father ― his only child and best friend.

After the plea, Martin ran into Coppock in the Navy Yard building’s lobby and asked her if she had a minute.

Escorted by Coppock’s attorney, they stepped into an empty room.

Martin said she had been crying.

“I put my arms out and I hugged her and kissed her forehead,” the 61-year-old recalled in an interview. “I told her: ‘This is bigger than you, OK?’”

The Fitzgerald was one of four Navy ships in the west Pacific’s 7th Fleet waters to suffer at-sea disasters last year, he pointed out.

A few months later, the John S. McCain would suffer its own collision, and another 10 sailors would die.

RELATED

Big Navy reviews have blamed the collision on a failure of basic seamanship, exacerbated by an operational tempo that left sailors little time to train.

“Unless you were telling me you were on all four ships in eight months’ time … no,” Martin told Coppock. “This is the Navy. You are no one but a scapegoat. All of you are.”

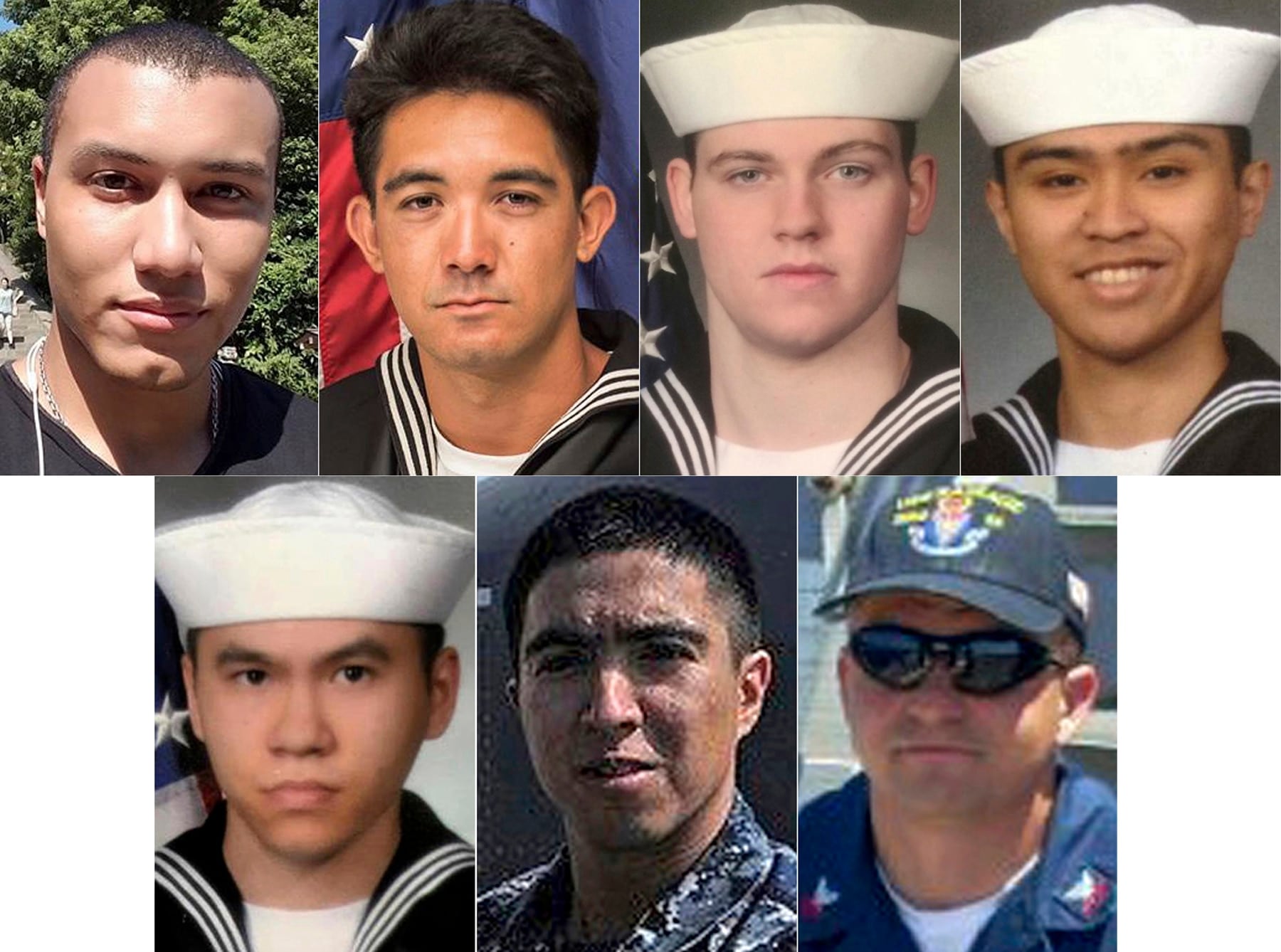

A year after the Fitzgerald disaster, the warship’s wake continues to ripple, and the tragedy remains undiluted for the family and friends who loved Martin and the other fallen sailors — Dakota Rigsby, Shingo Douglass, Tan Huynh, Noe Hernandez, Carlos Sibayan and Gary Rehm.

Some still have questions, while others are just trying to get through each day without a piece of themselves.

“I don’t think 24 years of life is a full life that’s been lived,” he said.

He remembers his boy as very smart and loving, a young man who took his dad’s advice regarding military service.

“He said, ‘Dad, you told me every man should go into the service because it rounds out the rough edges,’” Martin recalled.

A year after the Fitzgerald collision, Martin likened every day without Xavier to wearing smudged glasses.

“Nothing is as crisp as it used to be,” he said. “Some days I get up and I’m ready for work. I sit on the edge of the bed, and then I crawl right back in.”

RELATED

He knows he suffers from post-traumatic stress “real bad,” and he’s not sure if the counseling helps.

Alone in his home outside Baltimore, he sees commercials about troops battling PTSD, and his mind goes to dark places.

“All I can think is, ‘At least you made it home,’” Martin said. “And that’s (expletive) up.”

After the collision, a good friend and retired lieutenant colonel gently suggested that Martin have his neighbor hold on to his firearms for a while.

“There were times when I was seriously circling the drain,” he said. “But suicide’s the cowardly way out. That’s not the way to go see Xavier.”

Martin said his son was his best friend, and he’s been heartened to hear from Xavier’s friends that his boy felt the same.

He has only dreamed of Xavier twice. In one, he can’t get across a room crowded with family to speak to his boy.

In another, they are on base, Xavier says he’ll be back in an hour and never returns.

“I want to dream about him so bad,” Martin said. “But he won’t come to me.”

Xavier’s safe was one of the last things the Navy delivered to Martin.

Inside, among other personal effects, was a small book of motivational poems Martin had bought for his son years ago.

Darrold got a tattoo of a soundwave that is based on Xavier’s last voice mail message to his dad.

When the tattoo is scanned with a smart phone, the message plays.

Xavier had a tattoo of a saying his dad often told him growing up: “We’ll figure it out.”

After his death, Darrold Martin got the same tattoo.

There have been memorial ceremonies and dedications in Xavier’s name over the past year, but Martin said the grief still finds new ways to hurt.

“Some days it occurs to me that he’s not coming home,” Martin said. “And when it occurs to me, when that thought hits me, my stomach turns and it’s like the first time I’m realizing this. It’s the first time all over again.”

‘I’m out of kids’

The families of the seven lost Fitzgerald sailors and the loved ones of the 10 sailors who would perish in a similar collision aboard the McCain a few months later have formed an online support group of sorts.

While Martin blames the Navy for the collisions, he said that not every family sees it the same way regarding who was responsible.

But Martin, a veteran and defense contractor, remains angry at how the collision could happen, and the Navy’s handling of it all.

He blames the sea service.

RELATED

A friend asked him if he was worried about “messing with the Navy.”

“Can’t hurt me anymore,” he replied. “I’m out of kids.”

He has taken on a fatherly role for his son’s former shipmates, and bristles when he hears stories of how they’ve been treated.

Martin said they speak of a lack of counseling, of one attempting suicide, of other sailors on their new ships asking them: “How was it?”

“It’s not a roller coaster ride,” Martin said. “I’m really worried about these kids.”

Navy officials said they have provided mental health resources to the crew, and that ensuring they have the help they need is a top priority.

Small things grind Martin these days.

He tried to tell Navy leadership about the Fitzgerald sailors needing support, prompting a master chief at the Pentagon to ask him for their names.

“I said, ‘You think I’m just talking about two people?’” he said. “You think it’s just two people going through something? How about the entire ship?”

A year later, Martin worries that traumatized Fitzgerald sailors moving to other crews could endanger those ships.

The way he sees it, a struggling sailor isn’t focused on their next ship or next job, something he worries could lead to more disasters.

“Each of one of these sailors is like a CD that you haven’t ran a virus scan on,” Martin said. “You deploy these sailors around the world and insert them into their ship. They’re just walking malware and spyware. They’re your kids. What are you doing?”

‘Tan was on that ship!’

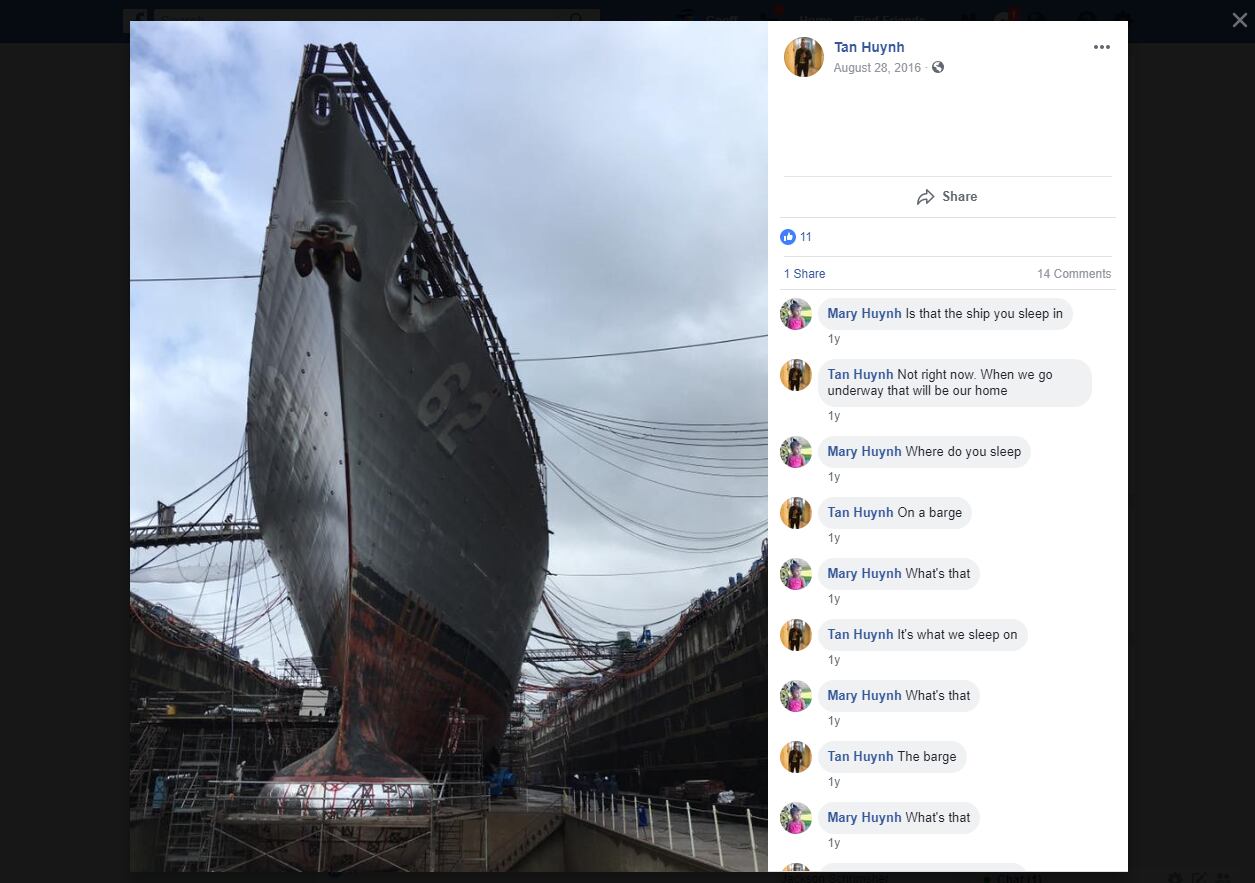

Tan Hunyh had thought about joining the Navy for a while.

The 25-year-old was the oldest of four siblings and enlisted to give back to his mother and see the world, according to his little sister, Mary Huynh.

“I’ll always regret not talking to him more about his main reasoning for enlisting,” she said. “What I thought seemed so miniscule to talk about then seems so important now.”

Tan’s birthday was June 16, the day before the collision.

Huynh said it was the last time the family spoke to Tan.

“’Happy birthday’ were our last words to him,” she said.

When the collision occurred, Huynh said she was browsing news on her phone but had forgotten that Tan was on the Fitzgerald .

Still, she remembered he was underway.

“After that, I just had a bad feeling in my gut,” Huynh said.

Later that night, her younger brother and sister ran into her bedroom, hysterical.

The Navy had just called.

“Tan was on that ship!” they screamed. “He’s not accounted for!”

They ran to wake up their mom.

Huynh said she’ll never forget the way her mom cried, noises she had never heard before.

“It was like someone was squeezing the life out of her and she couldn’t stop to take a breath,” Huynh said.

Like the rest of the Fitzgerald families, Huynh said her family no longer feels complete.

“Some days I feel guilty if I haven’t thought about him,” she said.

Her family has issues with how the Navy has handled things.

She said the family found out “a lot about what happened” through the media, before the Navy had contacted them.

Huynh said she still feels like the Navy hasn’t told the families all that happened that night, and she remains upset that the service has yet to release the full investigations into the collisions.

“I truly feel they left out a lot of events from that night in the final report and that alone is doing a disservice to all seven sailors,” she said. “If our Fitz families’ questions are being danced around, are we truly letting them rest in peace?”

Huynh called emails from Navy leadership expressing condolences “utter crap.”

“What can they do for us? Nothing,” she said. “We want answers, change and justice, and can they give that to us? I don’t think so.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.