“It’s only a matter of time before something horrible happens,” one shipmate warned.

“Our sailors do not trust the CO,” another noted.

It’s a “floating prison,” one said.

“I just pray we never have to shoot down a missile from North Korea,” a distraught sailor lamented, “because then our ineffectiveness will really show.”

These comments come from three command climate surveys taken on the cruiser Shiloh during Capt. Adam M. Aycock’s recently-completed 26-month command. The Japan-based ship is a vital cog in U.S. ballistic missile defense and the 7th Fleet’s West Pacific mission to deter North Korea and counter ascendant Chinese and Russian navies.

These comments are not unique. Each survey runs hundreds of pages, with crew members writing anonymously of dysfunction from the top, suicidal thoughts, exhaustion, despair and concern that the Shiloh was being pushed underway while vital repairs remained incomplete.

Frequently in focus is the commanding officer’s micromanagement and a neutered chiefs mess. Aycock was widely feared among sailors who said minor on-the-job mistakes often led to time in the brig, where they would be fed only bread and water.

RELATED

The survey reports offer a window into life in the Navy’s 7th Fleet, a Pacific command where leadership has admitted sailors are overworked and often insufficiently trained due to relentless mission pace.

“It feels like a race to see which will break down first,” one sailor wrote, “the ship or it’s [sic] crew.”

RELATED

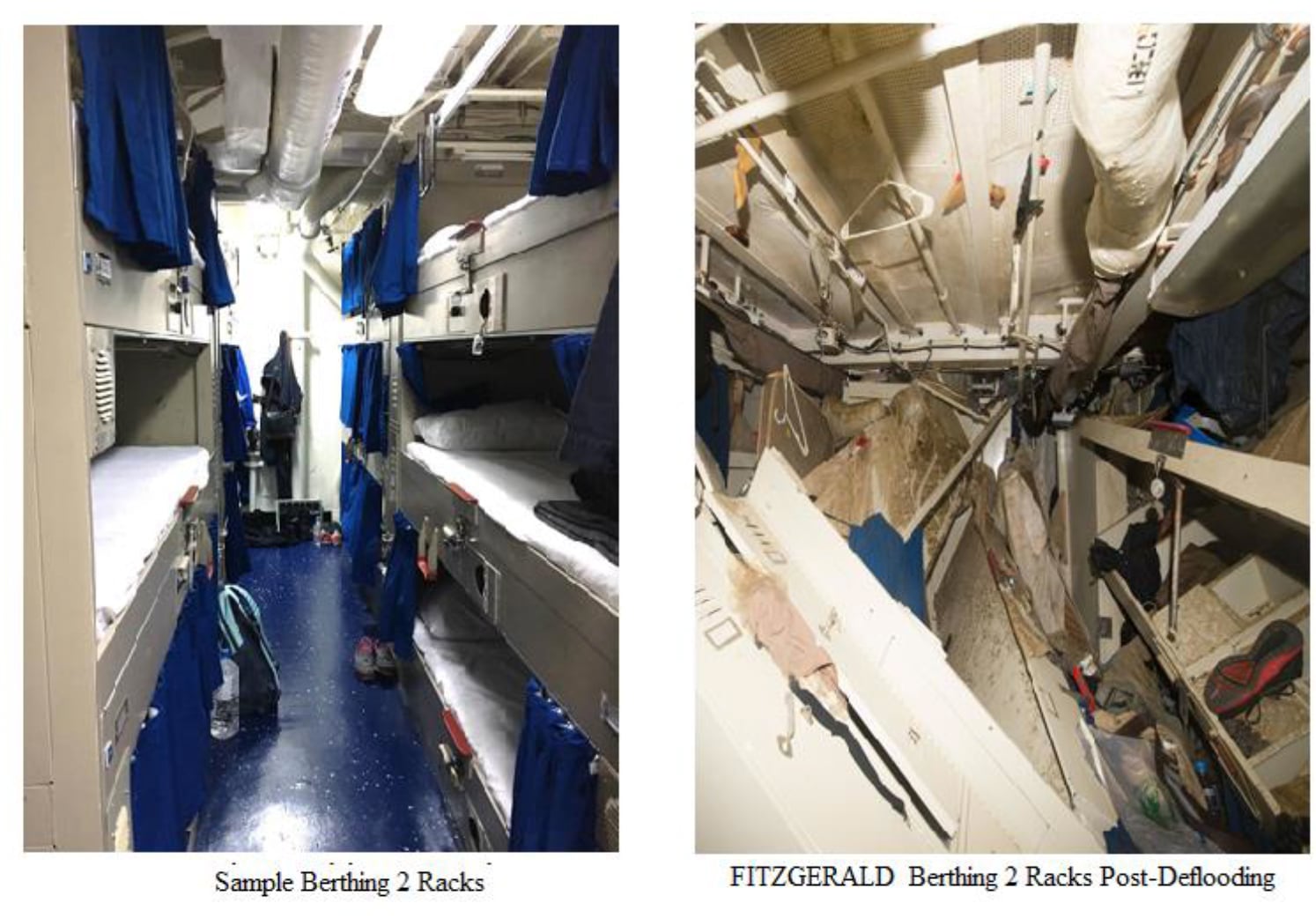

While government watchdogs have warned of such issues for years, the Navy’s problems have come back in to the spotlight in the wake of this summer’s at-sea collisions involving the destroyers Fitzgerald and John S. McCain, disasters that killed 17 sailors. The Shiloh belongs to the same chain of command as those two ships, where several top admirals were recently fired.

Despite the Shiloh’s sailor comments suggesting a ship in crisis, and at a time when the Navy stresses CO accountability, Aycock was not fired.

Navy officials declined to discuss survey details, but acknowledged that Aycock’s superiors at Task Force 70 were aware of problems after the first negative survey taken two months into his command.

Aycock’s bosses were tracking the dysfunction and counseling the captain, officials said, yet Aycock remained on the job and rotated out in a standard change-of-command ceremony on Aug. 30.

Aycock declined to comment for this story through a spokesperson at the Naval War College, where he now works as a researcher with the Institute for Future Warfare Studies. He commanded the Shiloh from June 2015 to August of this year. Previously, he served as commander on the destroyer Mahan and at Afloat Training Group Mayport in Florida.

Three retired Navy surface warfare skippers reviewed the surveys for Navy Times. They expressed dismay and questioned if the Navy did enough to correct the situation.

“The disrespect shown to Sailors in this ship was unforgivable,” said Wallace Lovely, a retired Navy captain and surface warfare officer who led Destroyer Squadron 31 after serving as the commander of the Frigate Samuel B. Roberts.

“The large number of lengthy comments from the respondents is not normal and the number of consistently negative comments is shocking.”

Such reports always include some disgruntled sailors, but Lovely said he had never seen it at the Shiloh’s level.

“I felt the tension while reading these surveys and can’t imagine what a Junior Sailor would be thinking while living through this scenario,” he said. “We’re lucky that a suicide or other casualty didn’t occur due to this oppressive environment.”

The Shiloh made news this summer when a sailor named Peter Mims went missing and was presumed overboard. The incident sparked a 50-hour search involving ships, aircraft and a carrier. In the end, Mims was found hiding on the ship.

Navy officials said Mims received non-judicial punishment for his actions but reasons for the incident remain unknown.

After Mims went missing, several sailors contacted Navy Times and voiced concern about the Shiloh, its CO and the crew, prompting Navy Times to submit a Freedom of Information request for copies of recent command climate surveys.

Rick Hoffman, a retired Navy captain whose years in uniform included command stints on the frigate De Wert and the cruiser Hue City, said he was “flabbergasted” by portions of the surveys and how they were “uniformly focused on the Captain and his leadership style.

“Almost all were negative and suggested he was insensitive to the crew’s needs,” Hoffman said. “It certainly appeared he was increasingly toxic over time.”

The reports depict a poster child for bad surface warfare officers, he said.

“Long hours, no communication, CO is a micromanager, chain of command is not functioning unit,” Hoffman said. “Crew pushed to exhaustion with no end in sight.”

The surveys suggest the Navy has learned nothing from prior toxic commands, said Jan van Tol, a retired captain who commanded several warships during his Navy career, including two from the Japan-based Forward Deployed Naval Forces of 7th Fleet.

He compared Aycock’s leadership to the notorious cruiser Cowpens’ CO, Capt. Holly Graf, who was relieved of command in 2010 for cruelty and maltreatment of her crew.

“If the Survey results in fact are accurate…it must raise serious questions of why no one in the ship’s external chains of command, including the administrative chain of command leading back to (Naval Surface Force Pacific), was aware of it,” van Tol said in an email. “Or if they were, why no one senior chose to take any remedial action. Neither of those alternatives is explicable.”

Navy officials would not comment on the survey remarks.

“Command Climate Surveys are a tool used to evaluate command morale and quality of life,” spokesman Cmdr. William Speaks said. “By their very nature, they must be private and confidential in order to be effective. In the interest of protecting the integrity of this process, we will not comment on feedback from our Sailors which is intended for Navy leadership.”

After the surveys are completed, ship commanders like Aycock are required to meet face to face for a debrief with their immediate supervisor to discuss the survey, according to Naval Surface Force spokesman Cmdr. John Perkins.

Aycock’s boss was Task Force 70 commander Rear Adm. Charles Williams, who was fired in September after 7th Fleet lost faith in his ability to command.

“Rear Adm. Charlie Williams provided specific guidance and mentorship to Captain Aycock regarding improving the climate aboard USS Shiloh,” Perkins said.

Perkins said that after the first negative survey report in August 2015 — two months into Aycock’s command — Williams directed the skipper to conduct surveys every six months, instead of annually.

The results from the second survey are dated about nine months later, in May 2016, while the third is dated in November.

“This was an effort to continually monitor the command climate and promote improvements,” he added.

“While USS Shiloh was meeting all operational requirements, a positive command climate should also be enforced,” Perkins said in an email.

Perkins said if Aycock was subject to any administrative discipline or punishment, it would not be something the Navy would comment on publicly.

A Navy official informed Navy Times on Oct. 6 that a fourth command climate survey was conducted shortly before Aycock’s departure from the Shiloh. A copy of that survey was not released to Navy Times, and it remains unclear whether that survey’s results differ from the other three.

Lovely, one of the retired skippers who reviewed the surveys, said he was surprised by the fact Aycock’s boss was aware of the issues.

“I am shocked to hear that leadership was tracking this nightmare and willing to be patient for a Major Commander to learn how to lead and respect,” he said. “It’s easy for me to say but if this were one of my 0-5 COs when I was Commodore…the relief process would have been quickly undertaken.”

Hoffman, another retired skipper, said there are very few signs that the surveys were briefed to Aycock’s bosses.

“If it did, it certainly didn’t have any positive result,” Hoffman said. “The comments in the later surveys suggest that the Captain became even more abusive, domineering and micromanaging over time. There was a steady downward trend over the three surveys.”

Shiloh’s sailors said goodbye to Aycock at the end of August, about 10 months after the November survey.

There were “red flags” on Aycock that required action, Hoffman said, “either to ensure the CO knew what his shortcomings were or to remove him altogether.”

Lovely also said “a red flag would have been raised” if higher-ups were tracking the surveys.

“Ultimately,” he said, “I must wonder where the process fell apart,” a question shared by sailors on the Shiloh.

“How is this not being investigated is beyond me,” one sailor wrote in the May 2016 survey.

RELATED

“I HOPE THIS SURVEY IS READ”

While Navy officials said Aycock’s boss was aware of the issues, the trajectory of the three surveys slopes downward in several categories, suggesting little improved during Aycock’s tenure.

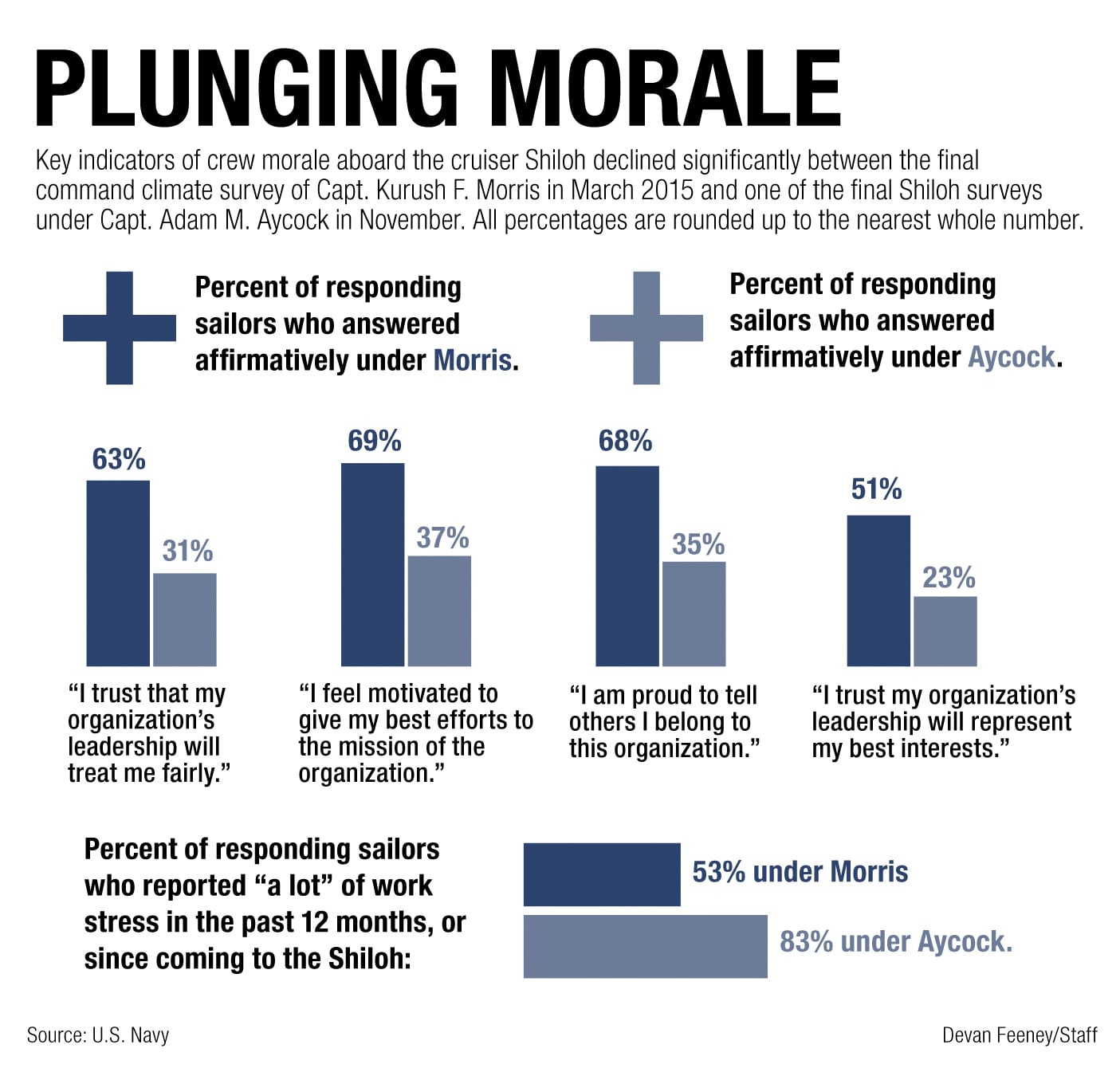

Several survey questions show a precipitous drop between the final survey of Aycock’s predecessor, Capt. Kurush F. Morris, and the November survey.

About 63 percent of responding Shiloh sailors said they trusted leadership to treat them fairly under the last survey of Morris’ tenure, in March 2015. That figure plunged to 31 percent in Aycock’s November survey.

Percentages of those proud to be part of the Shiloh, those motivated to do their best and those who trusted leadership with their best interests all fell among responding sailors between the final Morris survey and the November survey.

Perkins would not confirm the number of Aycock-related complaints received.

He said one Aycock complaint is still being investigated, but would not expound on it, citing the ongoing investigation.

“The Navy treats complaints about a ship’s commanding officer very seriously,” he said.

By the time of the third survey in November, some sailors were asking when help would arrive.

“I wonder how long will it take for ‘BIG NAVY’ to step in,” one sailor wrote. “I hope this survey is read, and change will come.”

Another sailor questioned the point of the surveys.

“This is the third survey I have taken in the past year and now don’t know what to expect from them,” the sailor wrote. “If the climate of the command has not changed by now obviously these are not a functional tool.”

The surveys are not mandatory, and participation among Shiloh sailors declined from the May 2016 survey report to the November report.

Hoffman, the retired skipper, theorized sailors may have felt there was no point in filling them out because nothing changed, a sentiment echoed in some comments.

“These kids are tired and emotionally beat,” he said.

As time passed, the sailors said the Shiloh became notorious along the Yokosuka, Japan, waterfront.

“It doesn’t make me proud when I tell someone that I’m on the SHILOH and they respond with ‘man that sucks,’” one sailor wrote.

“Even taxi drivers Know [sic] us by the ship who has the worst captain and people trying to commit suicide,” another wrote.

Hoffman wondered how Aycock’s bosses could not have known the extent of Shiloh’s issues if Yokosuka cabbies reportedly knew about them.

“I put the bulls eye back on [Aycock’s boss] for letting this fester,” Hoffman said. “He ignored the one tool that the Navy has in place to manage the internal mood of the ship and allowed this CO to continue to drag the ship into a deeper abyss.”

By the May 2016 survey, the entire waterfront knew of the Shiloh’s issues, “and how terrible the command has become,” one sailor wrote.

“I feel like I would be better off being a hobo in San diego [sic] than show up to work onboard USS Shiloh,” the sailor wrote.

RELATED

“THIS COMMAND IS RAN OFF OF FEAR”

Aycock “belittles the XO in public” and “has his hands in every process,” slowing everything up, a sailor wrote in the November survey.

A recurring theme of the surveys was the commanding officer’s micromanagement and how it rendered the chiefs mess powerless and unable to defend its lower-enlisted sailors.

“Most Khaki wonder how they will physically and mentally survive the remaining months and all are burnt out,” one sailor wrote in the May 2016 survey. “Our sailors do not trust the CO and because all decisions are made by the CO, the Sailors do not trust us. This is a very real problem.”

One sailor wrote in the November survey that the chiefs mess was no longer “the back bone of the ship” because they couldn’t lead their divisions.

“Division Officer {sic] are so scared of the CO that they can not make a decision,” the sailor wrote. “Dept Heads are all yes men who will never go against the grain. [Executive officer] and [command master chief] are exactly the same as DEPT HEADS. This command is ran off fear.”

Two months into Aycock’s tour, the August 2015 survey shows sailors scared of making basic mistakes and being taken to captain’s mast.

“They’re afraid to clean in the morning for clamp down in case they get caught using soap without gloves on because they know their career could be in jeopardy,” another sailor wrote in the May 2016 survey. “We’re all human, people make mistakes. Punishments should be handled at the lowest level possible. I feel my chain of command has no power in covering for their people.”

Sailors also complained of restrictive liberty policies that fostered more ill will.

“I now have to route a chit 3 days in advanced (sic) to stay overnight with my friends or visiting family members,” one sailor wrote. “I have to explain to my wife that no I cannot go out and stay at our friends (sic) house right off base because my captain doesn’t see me as an adult.”

The Shiloh no longer felt like home, according to one sailor, and the crew no longer felt like family.

“It’s a place we despise going to and cannot wait to leave,” the sailor wrote.

Several sailors cried foul in the May 2016 survey over Aycock brushing aside proposed Black History Month celebrations.

In an email to the crew responding to a CO suggestion box comment, Aycock denied shutting down Black History Month, but said that “we did not have a program that ensured that every diverse group was equally and fairly recognized.”

“We cannot recognize one group in such a way that another group feels excluded or less important,” Aycock wrote.

One sailor in the survey said that led some African American shipmates to conclude Aycock was racist, furthering the ship’s discordant vibe in the process.

“Some of the unnecessary stress that passes down makes the climate go down,” the sailor wrote.

“The only fair treatment,” another wrote, “is that everyone is equally treated as almost worthless.”

RELATED

“I NOW HATE MY SHIP AND MY JOB”

The Shiloh surveys under Aycock show respondents feeling exhausted, overworked and concerned about the mental health of themselves and their shipmates.

“If we went to war I felt like we would have been killed easily and there are ppl [sic] on board who wanted it to happen so we could just get it over with,” one sailor wrote.

A junior sailor wrote of feeling expendable and insignificant.

“My voice will never be heard unless a mistake was made, my tasks will never be acknowledged unless it was botched, and my presence will never be important unless I’m absent,” the sailor wrote. “I’m just an individual to force feed qualifications to, sweep the same p-way 4 times a day, constantly lecture about being responsible on liberty, and a crew member with a 33% chance to go to mast.”

Another decried how decisions were made “in a vacuum,” and that this led to “inhumane” work hours and an unsustainable operational tempo.

“It has taken its toll and its [sic] only a matter of time before something horrible happens,” the sailor wrote.

“I have been crying out for help to medical, chaplain and i [sic] am afraid to inform anyone due to a negative impact on my career,” another sailor wrote.

“I now hate my ship and my job,” one sailor wrote. “I now hate myself and the depressed, mindless person I’ve become. I feel like all the emotion and ambition i [sic] had is gone and i’m [sic] floating in chaos and confusion.”

The sailor said there were days when they would have committed suicide if it hadn’t been for their division officer and lead petty officer.

“But they look so depressed and exhausted too,” the sailor wrote.

In the May 2016 survey, several shipmates called out a policy where sailors who reported feeling suicidal were placed on restricted liberty.

“I am honestly worried people will stop asking for help due to the worry of being punished,” one crew member wrote. “Why would someone ask for help just to be forced to stay in the location that is making them feel that way.”

One November survey comment encapsulates the long hours on the Shiloh, a prevalent issue in 7th Fleet after the Fitzgerald and John S. McCain collisions.

“Members, especially leaders, are so worn out, beat down, and overworked, that they are almost incapable of being effective,” the sailor wrote.

Department heads did nothing, but it wasn’t their fault, the sailor continued.

“The incessant meetings, combined with 3-section watch, combined with all the cumbersome administrative processes onboard has made it almost impossible to accomplish the mission,” the sailor wrote.

Division officers “have to do all of the work that is pushed down from Department Heads, since they cannot complete anything because of their schedules. Leaders do not have time to take care of themselves, and it greatly impacts their ability, or lack thereof, to take care of their Sailors.”

The sailor suggested “major schedule and watch rotation changes.”

“We are all people,” the sailor wrote. “Not machines.”

“We are suffering,” another wrote. “We are so disrespected, beat down and unable to do our jobs.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at geoffz@militarytimes.com.