The Navy tried for four years to kill enlisted advancement exams, but officials say they’ll survive and become part of an expanded mixed system to move sailors up in rank.

“They have some disadvantages," Vice Adm. Bob Burke, the chief of naval personnel, told Navy Times. "They’re institutional. They’re impersonal. But they’re sometimes slow. But the thing I love about them is they’re absolutely impartial and they’re objective.

“That’s where the other services found some struggle with going to 100 percent command-level advancements. They had some things where there were accusations and perceptions of things that were not objective and fair.”

The Navy will concentrate over the next five years on tailoring the tests to a sailor’s unique job and skills.

Officials want enlisted personnel to take the exams when they’re ready for them, maybe even on a cellphone or computer tablet, and advance to the next pay grade the moment they become eligible instead of waiting months to get ahead.

The Navy also will move full speed ahead on expanding no-test advancements.

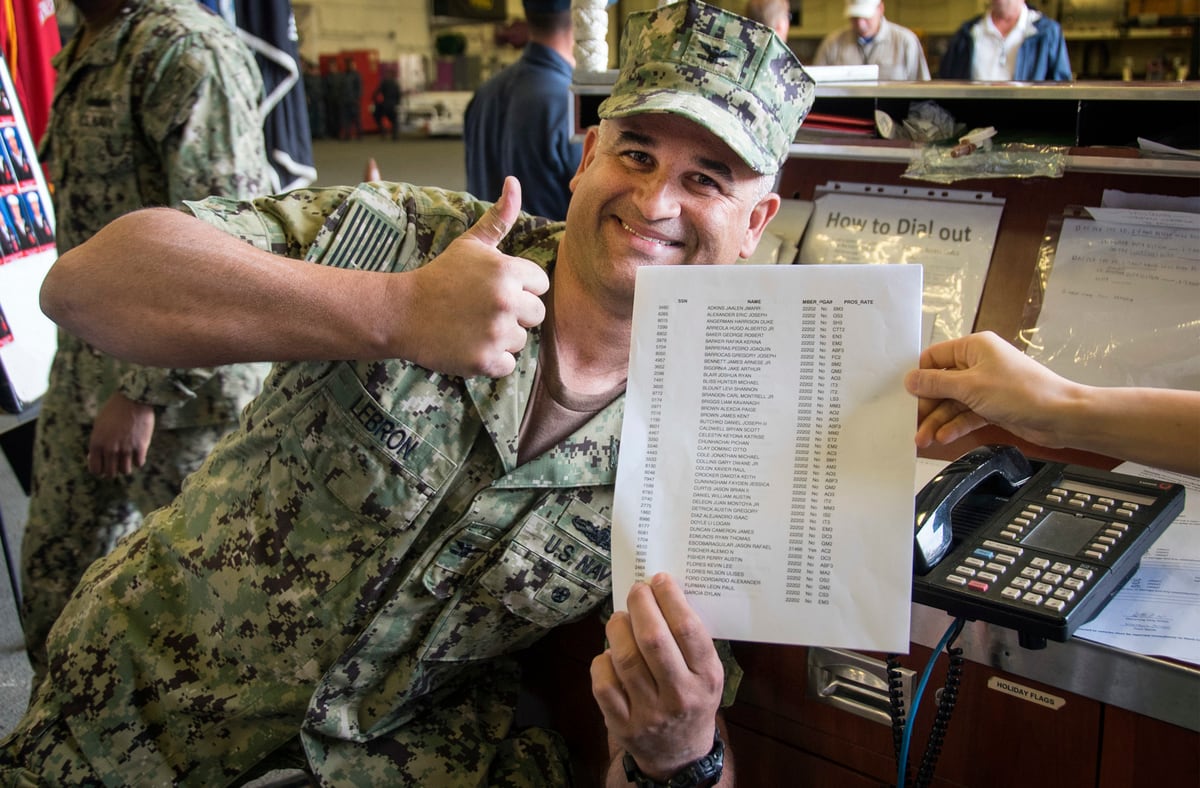

The Navy’s Meritorious Advancement Program (MAP) already allows commanding officers to spot advance 2nd class petty officers and below.

“I love MAP and our sailors love MAP and I want to continue to look at the potential to expand MAP and improve it as a tool,” Burke said. “But I also love our advancement exams."

Under MAP, commanding officers can advance 7,012 sailors this year. That’s 2,795 more quotas than they were given last year, and it’s part of a larger trend. Since 2015, the number of MAP advancements has risen 213 percent.

But the program hasn’t been without controversy.

Command-level advancements go back four decades, but officers once were reluctant to use all the quotas they were given.

Known as the Command Advancement Program before 2015, the initiative came under fire after enlisted personnel planners blamed spot advancements on overmanning headaches in several ratings.

Other critics grumbled that some commanders used spot advancements simply to boost sailors who were poor test takers.

Both Burke and Adm. Bill Moran, the 39th vice chief of naval operations, sought to preserve and expand the program by making commanding officers and community managers coordinate the advancements and prevent overmanning.

Commanding officers now are limited to when they can use MAP. The advancement season begins in July and runs through August, with the number of slots available based on the size of a unit.

Three years ago, command-level advancements comprised only about 5 percent of the Navy’s total. But last year it stood at 15 percent, and officials want to hike that to a quarter of all advancements.

“We’ve reached that number in some ratings and pay grades,” Burke said. “But we’ve still got room to expand that in others. E-4 is approaching 25 percent, but E-5 and E-6 have room to grow, so we’ll continue to walk those numbers up to get us to that overall 25 percent.”

To Burke, what really matters is that the Navy bases advancements on the knowledge and maturity of individual sailors and “not a calendar or the clock.”

RELATED

That extends to the traditional advancement system, too.

Burke wants to streamline the process. He’s already approved a reform championed by the fleet master chiefs to remove professional military knowledge questions from advancement tests.

Beginning in October, sailors will take that online. Sailors who pass won’t have to retake it until they reach the next pay grade.

“I think we’re four to five years away from the completely tailored electronic exam,” Burke said. “But this will be evolutionary as we’ll continue to improve the paper exam right up until we have the ability to put it online.”

The Navy will use the new online exams to explore future innovations in test taking.

Burke predicts that over the next year or two the Navy will roll out rating exams based on the jobs the sailors actually do in the fleet, targeting the Navy Enlisted Classifications they hold.

“Sailors will have to study less of the extraneous stuff that’s not tied to their jobs,” Burke said. “It’s going to be less work to study, going forward, because it will become more relevant to what they do every day.”

By freeing sailors from the traditional twice-annual cycle of advancements and scrapping paper tests, they can take the exams on the day they become eligible to move up a rank.

The test isn’t everything — the advancement formula includes factors like job performance assessments, most individual awards and college credits — but the new system will use the exams to help generate scores that rank sailors against their peers across the Navy.

That happens twice yearly now but soon the “rack and stack” of personnel competing for rank will be constantly updated. Sailors will be able go online and see where they stand on the promotion ladder.

If they want to creep up on their competition, they can study more and retake the test to land a higher advancement score.

Officials already tweaked the formula to emphasize performance over tenure, trimming the weight once given to time spent in grade. Now they’re exploring how off-duty education should tilt the formula, too.

“We’ll always be looking for ways to improve how we measure our sailors for advancement,” Burke said. “It’s always going to be a work in progress as technology and ways to gauge merit and performance improve.”

Mark D. Faram is a former reporter for Navy Times. He was a senior writer covering personnel, cultural and historical issues. A nine-year active duty Navy veteran, Faram served from 1978 to 1987 as a Navy Diver and photographer.