The Navy will deplete its fiscal year 2019 Tuition Assistance coffers in a few weeks.

“We estimate funding will be exhausted by May, but continue to explore alternative funding options,” Capt. Amy Derrick, spokeswoman for the Navy’s personnel chief, told Navy Times in a prepared statement.

Although the Pentagon pegged $75 million for TA this year, more than $60 million already has been spent, just when sailors are beginning to eye fall classes.

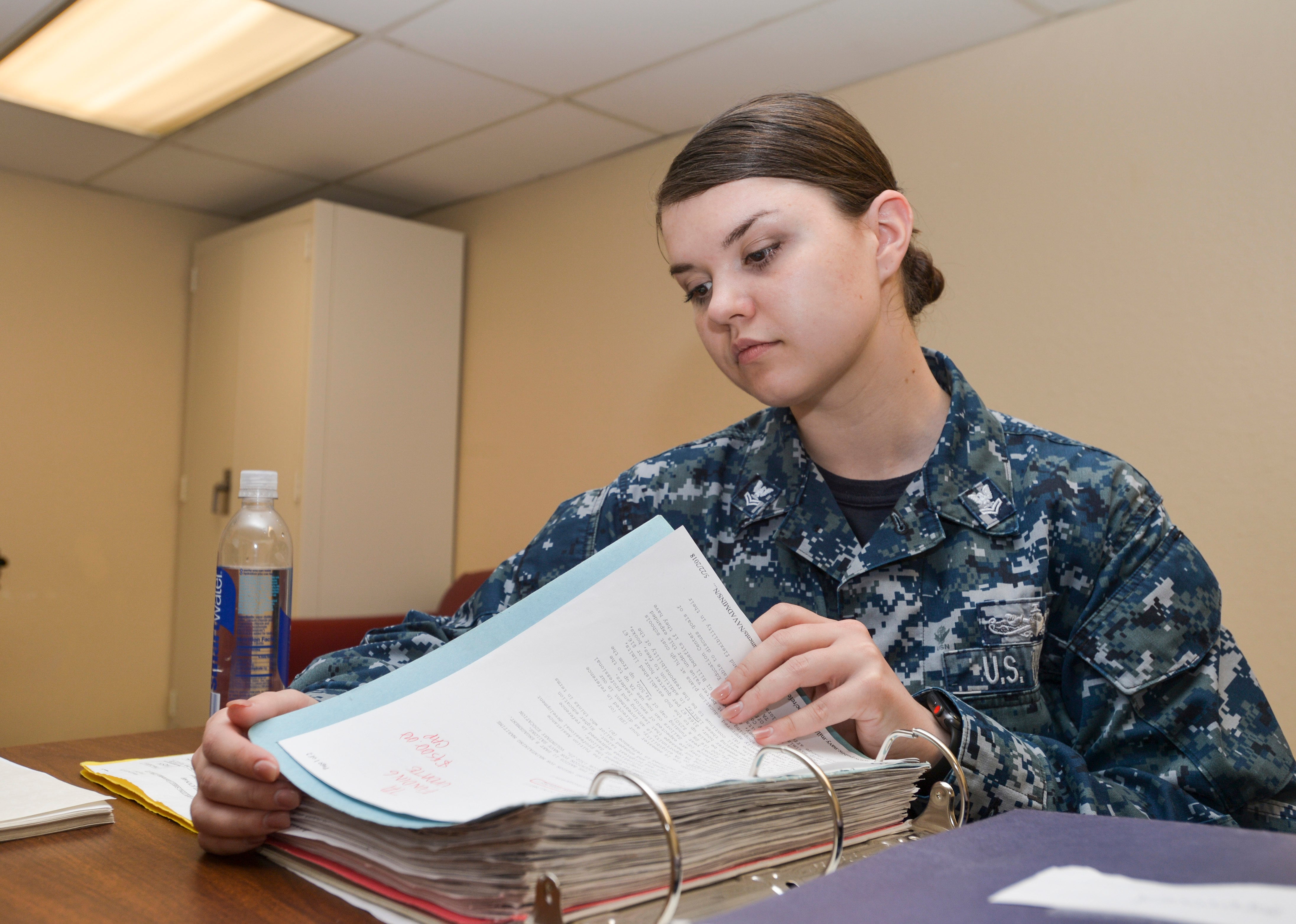

About 13 percent of the Navy’s uniformed personnel are using TA now, accruing college credits on the Pentagon’s dime without dipping into their GI Bill benefits.

Derrick said sailors already enrolled in TA with approved education plans and paid vouchers won’t be affected because their funding already has been allocated.

But no new FY 2019 vouchers will be issued once the dollars drain out.

The current crunch came because of rising demand for TA funding, according to records released to Navy Times.

As of March 22, the military counted 5,384 more sailors using TA this year compared to 2018.

That figures out to 19 percent more sailors receiving TA assistance to pay for 36 percent more courses than officials anticipated. Add it up and it’s $15.9 million in unexpected costs, Derrick said.

But Derrick and other military leaders told Navy Times that doesn’t mean sailors who want to use TA this fall won’t get it.

“We’ve never walked away from Tuition Assistance,” Master Chief Petty Officer of the Navy Russ Smith told Navy Time. “The Navy has always believed in it and we always will. We are committed to it.”

In 2017, for example, the Navy budgeted $85 million but had to find $2 million to cover a shortfall at the end of the fiscal year. Eventually, 42,920 sailors took 125,585 courses funded by TA.

The following year, the Pentagon set the TA budget at $83 million, $8 million less than was needed.

Officials found the cash to cover the increased demand, allowing 43,159 personnel to take 131,410 courses.

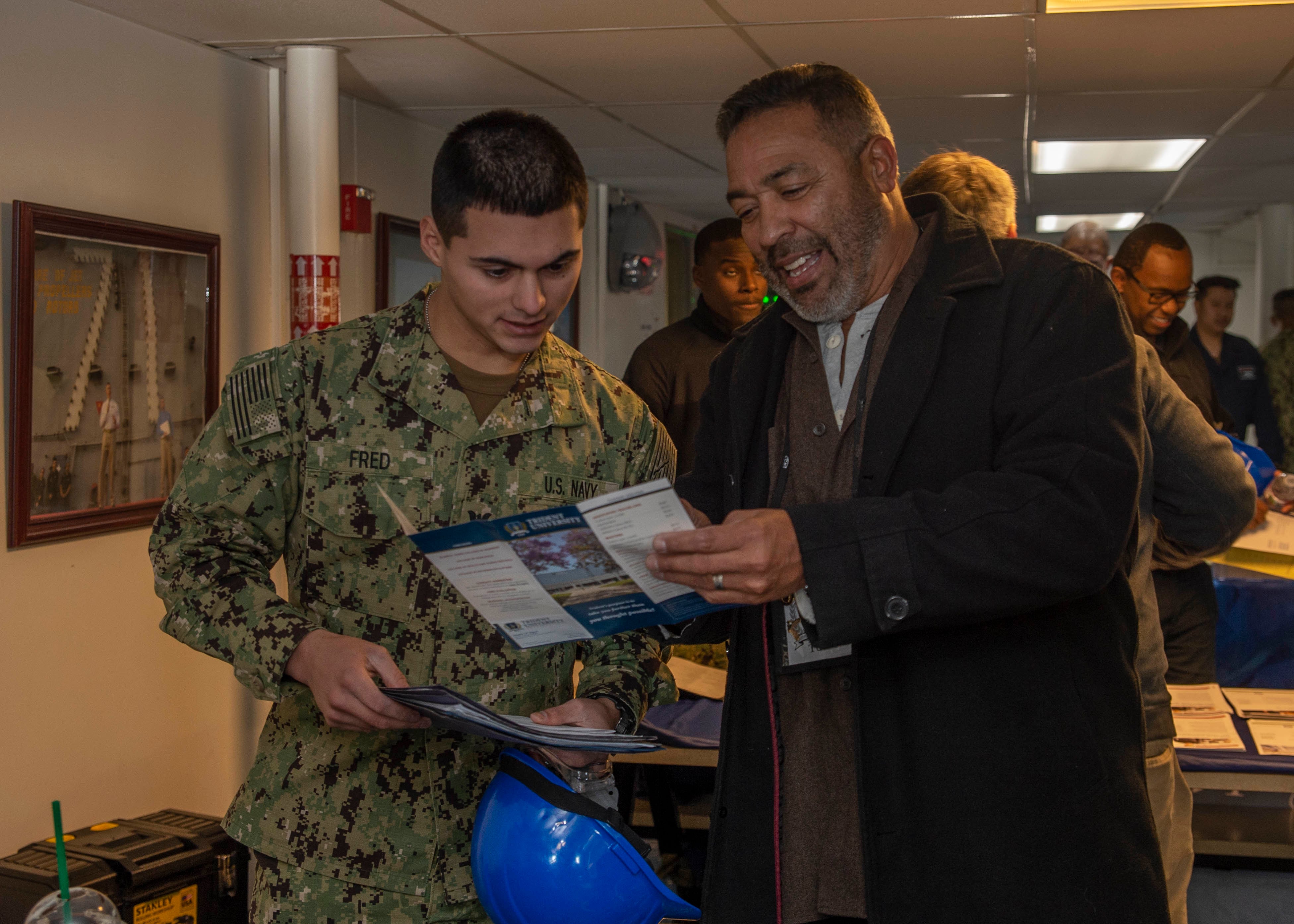

The rising popularity of Tuition Assistance is being driven by Navy reforms that made it easier for sailors to apply for the funds and take more courses while they’re in the program.

That began in 2016, when the service shuttered 20 base Navy college offices and began ramping up virtual education counseling online.

“When we closed the Navy college offices and went to the centralized, online system, many predicted we’d have fewer people enrolling in college,” Smith said. “But, in fact, it’s gone way up because we’ve made it easier to enroll, easier to get into a class, the process is more simplistic and streamlined to get approval.”

MCPON told Navy Times that he had reservations the internet-based system would work well, but he was happy to discover that the shift “had a tremendous effect and impact” by making it a more convenient way to enroll in college courses.

Then the Navy decided last year to loosen limits on how much TA sailors can use.

Previously, the service had capped TA-funded coursework at 16 credits annually per student, with no more than $250 allotted for each credit hour.

Starting last June, however, the Navy nixed the caps, letting sailors take as many courses as they could handle, up to a $4,500 annual spending limit set by the Pentagon.

That led to sailors of all ranks taking 5 percent more courses than in 2017, a trend that apparently continued this year.

“We see the increased demand signal for TA as a good thing, because college teaches critical thinking,” MCPON Smith said. “We’re happy about that.”

But the increasing popularity of the Navy’s TA program comes amid greater uncertainty about the shape it might take in an era of radical changes in the sea service’s higher educational system and diminishing dollars allotted for outside college credits.

Rolled out on March 12, the White House’s 2020 defense spending plan whittled $6 million out of next year’s TA budget.

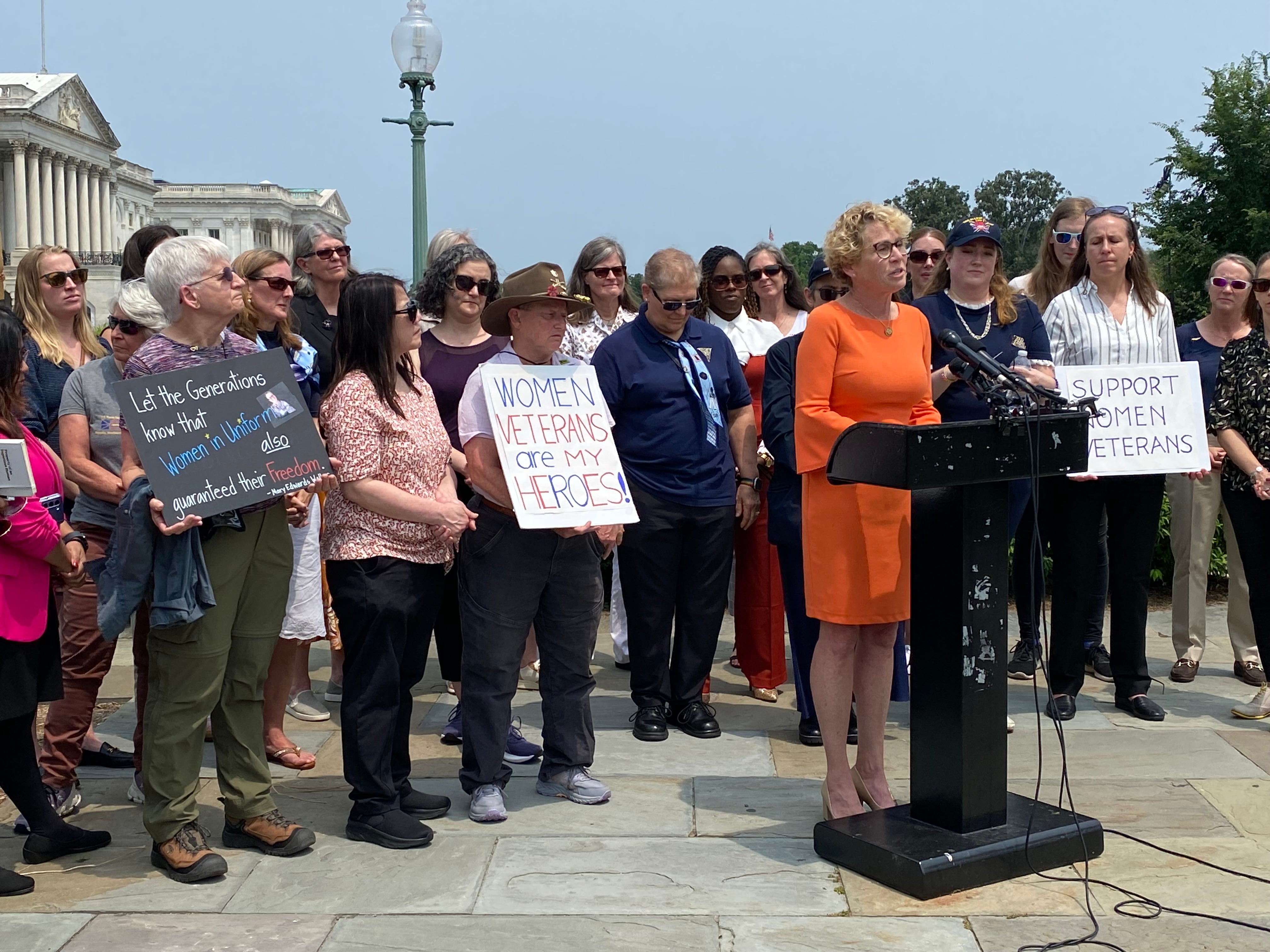

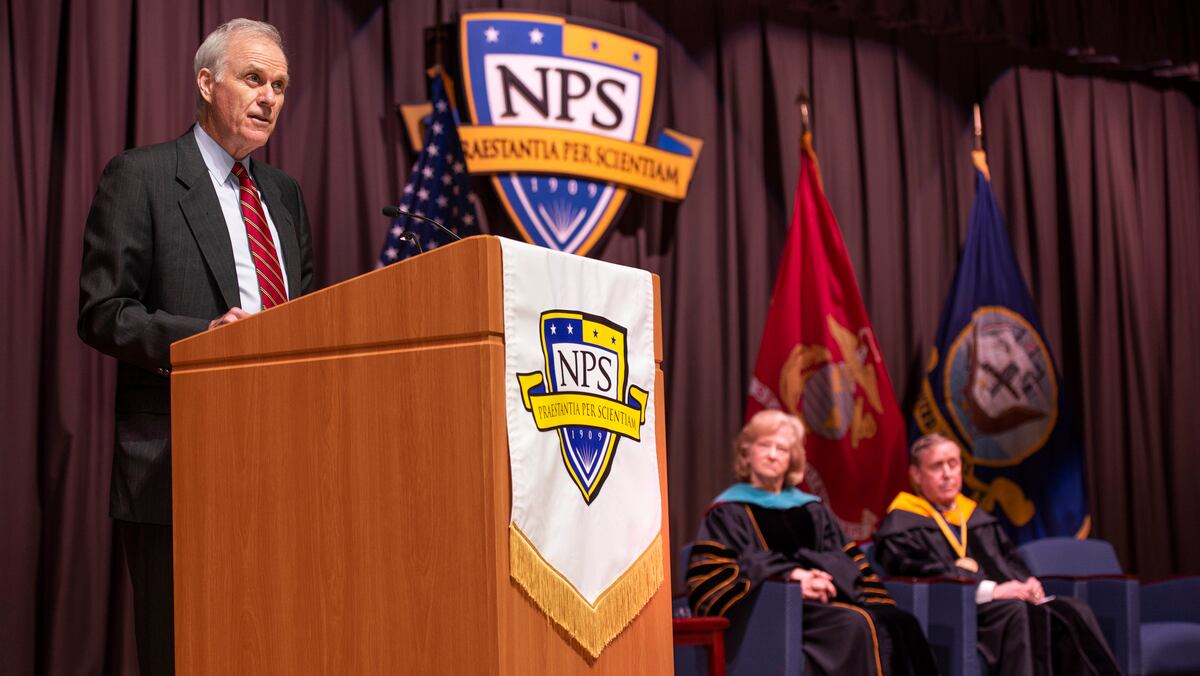

That announcement came only five weeks after Secretary of the Navy Richard Spencer launched his “Education for Seapower” campaign, a push to hike and hone critical thinking skills in the Navy and Marine Corps.

Spencer’s Feb. 5 memo hinted at a major restructuring of the educational system for both officer and enlisted personnel under a single department university accredited to grant diplomas, from two-year associate degrees up to advanced post-graduate work.

Spencer’s proposed reforms also called on military leaders within the next two years to craft a community college similar to what the Air Force offers its enlisted personnel, but there’s been no public announcement about which courses and majors it will offer.

During a Jan. 16 address at the annual Surface Navy Association conference in Arlington, Virginia, Spencer raised eyebrows when he candidly called for the “education that we need as a naval force,” the sort of “professional management” training that will “benefit the corporate body.”

“I don’t really care about someone, to be very frank with you, going off and getting an art history major. I’m being totally selfish, but if these are my dollars, I want you to be learning something that is going to help this institution,” he said.

RELATED

That’s not how TA works today.

Envisioned by Congress as an educational assistance program to benefit individual sailors, mostly off-duty enlisted personnel, TA covers tuition costs at accredited colleges, universities and vocational/technical institutions recognized by the U.S. Department of Education.

Records released to Navy Times reveal that in FY 2016 and 2017, the TA program averaged 33,241 participants annually in pay grades E-1 through E-6.

But it was disproportionately used by first and second class petty officers, who combined to make up 59 percent of all Navy students getting TA help.

In fact, during those two years 4,600 more first class petty officers used TA than all the officers, warrant officers and chiefs in the program combined, according to the Navy data.

With fewer dollars budgeted to the Navy’s TA program and growing concerns that junior personnel are spending too much of their time on volunteer work, collateral duties and college coursework, debate continues on whether leaders need to clamp down on TA for petty officer third class sailors and below.

Navy records show they gobble up about 20 percent of the Navy’s annual TA funding but the larger concern is that they need to master their ratings before going to college.

“We are still taking a look at it, the impacts and the budget to make sure we’re being as responsible as we can,” MCPON Smith said.

To Smith, if the Navy’s goal is to “eliminate distractions” so that junior sailors know how to do the job they volunteered to do “in order to fight and defend this country,” then it might be time to pare back the amount of college coursework they’re trying to complete.

But sailors who mastered their ratings can expand their critical thinking skills through college courses, making them better leaders, too.

RELATED

Revamping the Navy’s TA system isn’t a call MCPON makes. That burden falls on his superior flag officers.

“They’re still looking at all that and I’m sure they’ll come to a right decision,” Smith said. “Because at the end of the day, if we put to sea and come under attack and our sailors aren’t prepared, because they’ve been distracted and not focused on their job, the end result won’t be good.”

The Navy’s leaders have restricted TA in the past. Concerned by a rising number of unfinished courses, in 2010 they blocked sailors in their first year at new duty stations from seeking the tuition aid.

But four years later they greenlighted commanding officers to approve TA for junior sailors who can balance their day jobs with college coursework.

“We are reviewing our current TA policy in light of decreased funding to ensure it meets the needs of our sailors and is balanced with the needs of the Navy,” spokeswoman Derrick said, “The current policy remains in effect. We will announce any changes, should there be any at that time.”

RELATED

Junior personnel interviewed by Navy Times urged service leaders to forgo restricting TA dollars,and instead expand the program.

“I think that not allowing E-4 and below to use TA would be sending a bad message to people who would be joining for educational purposes,” said Hospital Corpsman 2nd Class Quentin Moore, who’s stationed in San Antonio.

“Being a person who joined for educational purposes myself, and had worked in an education and training office, I think that this would be bad for new accessions and for retention.”

Moore wants the Navy to nearly double the TA funding cap to $8,000 per year, allowing sailors to take more classes offered by colleges they’re already attending.

Others urge Navy leaders to hike TA for those in graduate programs.

“The one improvement I would like to see the Navy do with TA is to be able to have a TA program for a master’s degree that is a higher amount than TA for a bachelor’s degree,” said Fire Controlman (Aegis) 1st Class Aaron Larson, who’s stationed in Dahlgren, Virginia.

“Master’s degrees are much more expensive and the amount of TA that is given doesn’t provide much help.”

Regardless of TA’s future, Pentagon leaders have telegraphed increased funding for a similar program sailors can use to earn diplomas.

The Navy College Program for Afloat College Education offers both instructor-led and distance education courses to personnel at sea.

Its budget doubled to $8 million this year and the Pentagon’s 2020 spending plan adds $1 million more.

In 2018, sailors took 2,836 classes in the program but that’s expected to grow to nearly 10,0000 next year.

Mark D. Faram is a former reporter for Navy Times. He was a senior writer covering personnel, cultural and historical issues. A nine-year active duty Navy veteran, Faram served from 1978 to 1987 as a Navy Diver and photographer.