Enterprise, the world’s first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, could become the first Navy vessel of its kind to be scrapped by a commercial breaker — if the Pentagon gets its way.

Last week the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard pointed to a website that outlines four potential plans to finally dispose of the Big E, a warship that faithfully served the fleet for 51 years before it was deactivated in 2012.

Five years and $750 million later, workers had siphoned out the flattop’s nuclear fuel and the Navy decommissioned it. Now it’s just a rusting hulk tied up at the Huntington Ingalls Newport News shipyard.

The four proposals include:

- Partially dismantling the carrier at a commercial breaker by removing all parts of the ship except the nuclear reactor compartments, which will be transported to the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard & Intermediate Maintenance Facility in Bremerton, Washington. After processing the parts will be chopped into eight sections and shipped again to the U.S. Department of Energy’s Hanford Site for disposal.

- Following the same plan, except for packaging the reactor compartments into four sections for shipment to Hanford. Each package would contain two of the ship’s reactor plants.

- Dismantling the carrier at commercial shipyards, including cutting apart the eight reactor plants into several hundred small containers for disposal at established Department of Energy or licensed commercial waste facilities in Washington, Utah, Texas or South Carolina.

- Doing nothing. The Enterprise would be mothballed at an unnamed shipyard with "periodic maintenance to ensure storage continues in a safe and environmentally responsible manner.”

Last fall, the Navy contracted with the Huntington Ingalls Newport News shipyard, agreeing to pay $34 million for stowage and upkeep of the vessel over the next three years.

RELATED

A 2018 report by the Government Accountability Office estimated it could cost between $1 billion and $1.5 billion to dispose of the Enterprise at the Puget Sound shipyard.

Due to work backlogs, that also would take about least 15 years.

GAO pegged the price tag for breaking the Big E at between $750 million and $1.4 billion if completed by commercial scrappers, and it could be completed in the next decade.

In 2016, the Navy asked contractors to submit disposal bids but the effort was halted a year later due to a scuffle with the Nuclear Regulatory Commission over which agency had the legal authority to oversee reactor work in the private sector.

Although Navy officials remain mum on the spat, the differences appear to be sorted out and the process is moving forward.

“The Navy will examine a range of options for overseeing compliance with applicable federal laws,” said Puget Sound Shipyard spokesman J.C. Mathews.

"We are at the early stages of this process, and we are not ready to discuss the regulatory structure at this time."

Those details, he said, will be spelled out when a final impact statement is published in “early 2021,” although the timetable could change.

Over the decades, the Navy at Puget Sound has safely packed and shipped to Hanford 133 military reactor compartments pulled from 124 nuclear vessels, Mathews said.

GAO noted that civilian contractors also have disposed of 32 commercial reactors.

The proposals don’t specify potential commercial breakers, only locations in Newport News and Brownsville, Texas.

Officials are planning public meetings to discuss the proposals in both communities, plus Bremerton.

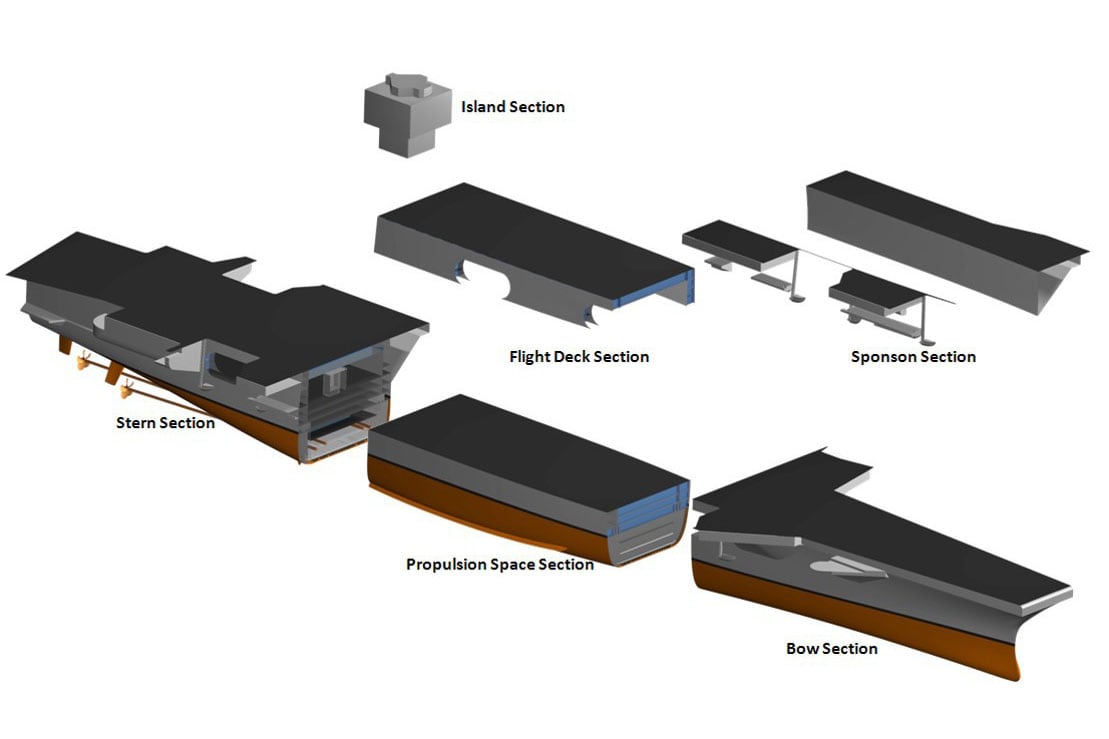

The first two options the Navy is considering begin with the same process.

The Enterprise would be dry-docked and then split into three sections, isolating the middle “propulsion spaces” holding the reactors.

That section would be stripped of the ship’s island, flight deck and any other spaces above the hanger deck.

What’s left would be sealed up and towed around South America to Puget Sound.

That’s because at nearly 133 feet long at the waterline, the towed propulsion section is too large for the Panama Canal.

The widest ships to make that transit were the Navy’s four Iowa-class battleships, which passed through the canal with six inches to spare on each side, Mathews said.

RELATED

It’s much easier to store or scrap non-nuclear warships.

It costs the Navy roughly $200,000 to mothball a non-nuclear carrier every year, according to Naval Sea Systems Command.

But officials have expedited their removal. Between 2014 and 2017, the Navy sent the carriers Constellation, Ranger and Independence to breakers. And the service plans the same fate for the carriers Kitty Hawk and John F. Kennedy, the only two ex-flattops still managed by the Navy.

Officials have been shopping the ex-Kitty Hawk to scrappers since late 2017, with no takers.

In 2017, the Navy also removed the former flattop John F. Kennedy from the museum ship donation list and earmarked it for “disposal by dismantling.”

In its 2018 report, GAO investigators urged the Navy to find alternatives to expensive nuclear scrapping options because the Nimitz-class aircraft carriers are beginning to reach retirement age, too.

Nimitz is expected to end its service life in 2025, followed by the Dwight D. Eisenhower in 2027, according to the Naval Sea Systems Command.

The good news is that these warships have two-reactor nuclear propulsion plants, which makes them easier to scrap than the Big E.

Puget Sound’s Mathews told Navy Times that “dry dock space for ship dismantlement” comes on a space available basis when not needed for “other mission requirements,” such as keeping warships operating for the fleet.

“Recycling work is currently underway on three submarines,” Mathews said. “Generally speaking, though, in recent years we average shipping two reactor compartments to the Hanford Site for disposal annually.”

He said 14 vessels are at the yard awaiting dismantling and more are expected to arrive as other ships are deactivated.

By law, however, nuclear-powered warships can’t be officially decommissioned until their reactors are drained of heavy water and their radioactive cores are removed and stored.

Mark D. Faram is a former reporter for Navy Times. He was a senior writer covering personnel, cultural and historical issues. A nine-year active duty Navy veteran, Faram served from 1978 to 1987 as a Navy Diver and photographer.