Around 4:00 a.m. on July 2, 1839, Joseph Cinqué led a slave mutiny on board the Spanish schooner Amistad some 20 miles off northern Cuba.

The revolt set off a remarkable series of events and became the basis of a court case that ultimately reached the U.S. Supreme Court. The civil rights issues involved in the affair made it the most famous case to appear in American courts before the landmark Dred Scott decision of 1857.

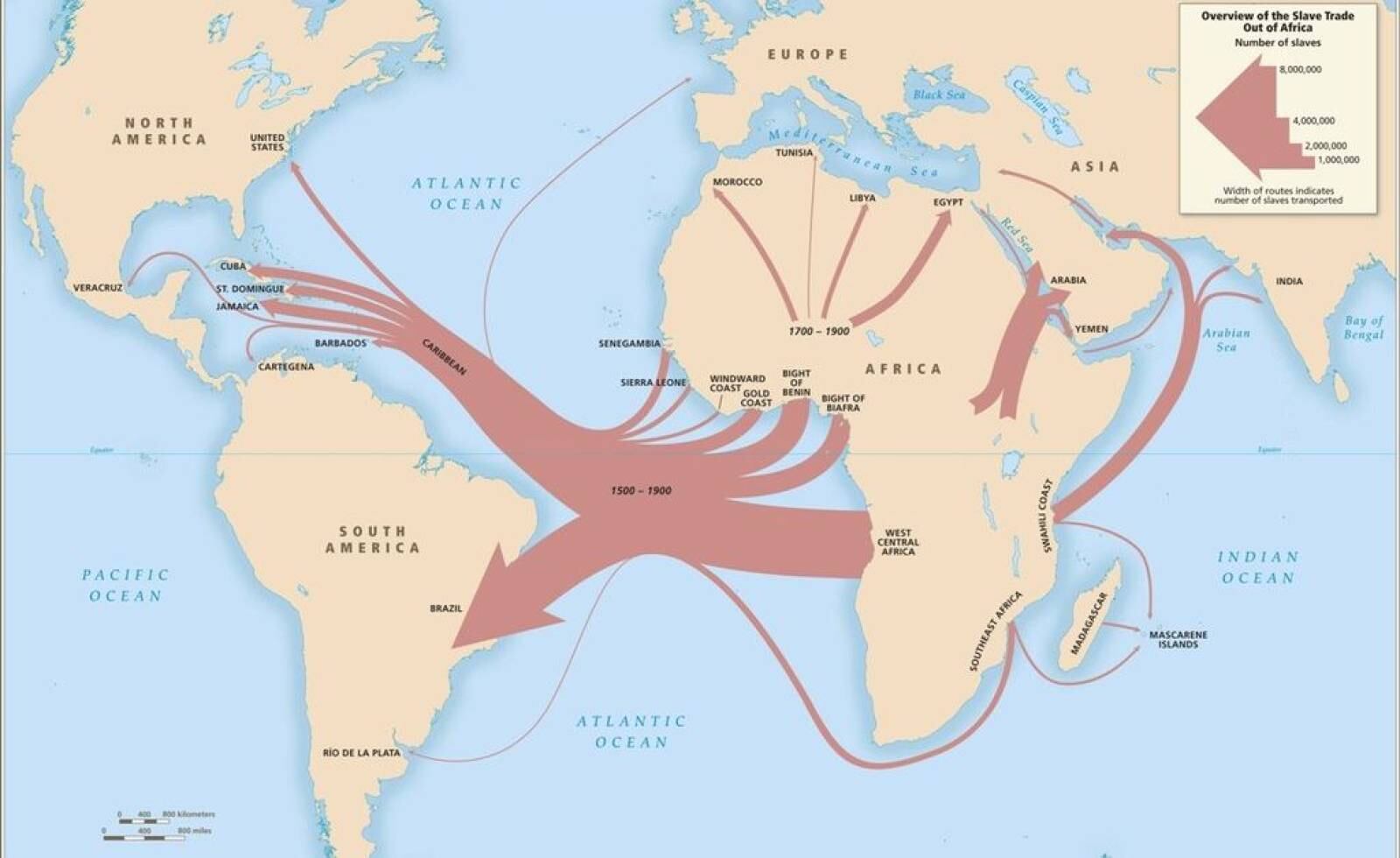

The saga began two months earlier when slave trade merchants captured Cinqué, a 26-year-old man from Mende, Sierra Leone, and hundreds of others from different West African tribes. The captives were then taken to the Caribbean, with up to 500 of them chained hand and foot, on board the Portuguese slaver Teçora.

After a nightmarish voyage in which approximately a third of the captives died, the journey ended with the clandestine, nighttime entry of the ship into Cuba — in violation of the Anglo-Spanish treaties of 1817 and 1835 that made the African slave trade a capital crime.

Slavery itself was legal in Cuba, meaning that once smuggled ashore, the captives became “slaves” suitable for auction at the Havana barracoons.

In Havana, two Spaniards, José Ruiz and Pedro Montes, bought 53 of the Africans — including Cinqué and four children, three of them girls — and chartered the Amistad.

The ship, named after the Spanish word for friendship, was a small black schooner built in Baltimore for the coastal slave trade. It was to transport its human cargo 300 miles to two plantations on another part of Cuba at Puerto Principe.

The spark for the mutiny was provided by Celestino, the Amistad‘s cook. In a cruel jest, he drew his hand past his throat and pointed to barrels of beef, indicating to Cinqué that, on reaching Puerto Principe, the 53 black captives aboard would be killed and eaten.

Stunned by this revelation, Cinqué found a nail to pick the locks on the captives’ chains and made a strike for freedom.

On their third night at sea, Cinqué and a fellow captive named Grabeau freed their comrades and searched the dark hold for weapons. They found them in boxes: sugar cane knives with machete-like blades, two feet in length, attached to inch-thick steel handles.

Weapons in hand, Cinqué and his cohorts stormed the shadowy, pitching deck and, in a brief and bloody struggle that led to the death of one of their own, killed the cook and captain and severely wounded Ruiz and Montes.

Two sailors who were on board disappeared in the melee and were probably drowned in a desperate attempt to swim the long distance to shore.

Grabeau convinced Cinqué to spare the lives of the two Spaniards, since only they possessed the navigational skills necessary to sail the Amistad to Africa.

Instead of making it home, however, the former captives eventually ended up off the coast of New York.

Cinqué, the acknowledged leader of the mutineers, recalled that the slave ship that he and the others had traveled on during their passage from Africa to Cuba had sailed away from the rising sun; therefore to return home, he ordered Montes, who had once been a sea captain, to sail the Amistad into the sun.

The two Spaniards deceived their captors by sailing back and forth in the Caribbean Sea, toward the sun during the day and, by the stars, back toward Havana at night, hoping for rescue by British anti-slave-trade patrol vessels.

When that failed, Ruiz and Montes took the schooner on a long and erratic trek northward up the Atlantic coast.

Some 60 days after the mutiny, under a hot afternoon sun in late August 1839, U.S. Navy Lt. Cmdr. Thomas Gedney of the brig Washington sighted the vessel just off Long Island, where several of the schooner’s inhabitants were on shore bartering for food.

He immediately dispatched an armed party who captured the men ashore and then boarded the vessel.

They found a shocking sight: cargo strewn all over the deck; perhaps 50 men nearly starved and destitute, their skeletal bodies naked or barely clothed in rags; a black corpse lying in decay on the deck, its face frozen as if in terror; another black with a maniacal gaze in his eyes; and two wounded Spaniards in the hold who claimed to be the owners of the Africans who, as slaves, had mutinied and murdered the ship’s captain.

Gedney seized the vessel and cargo and reported the shocking episode to authorities in New London, Connecticut.

Only 43 of the Africans were still alive, including the four children. In addition to the one killed during the mutiny, nine had died of disease and exposure or from consuming medicine on board in an effort to quench their thirst.

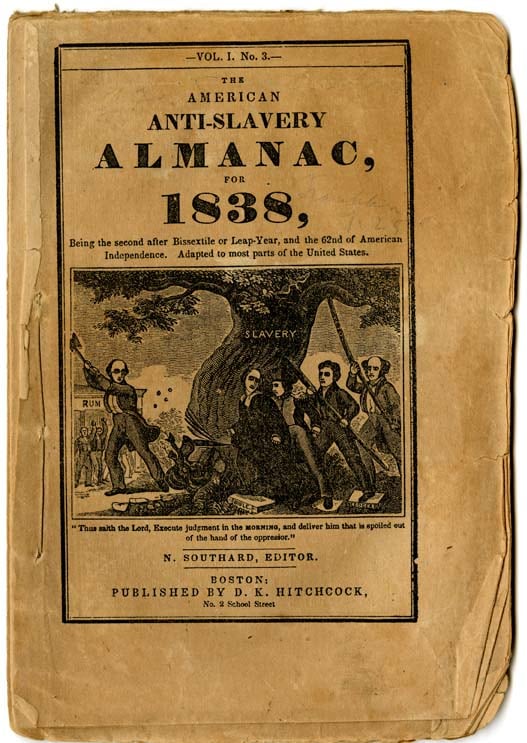

The affair might have come to a quiet end at this point had it not been for a group of abolitionists.

Evangelical Christians led by Lewis Tappan, a prominent New York businessman, Joshua Leavitt, a lawyer and journalist who edited the Emancipator in New York, and Simeon Jocelyn, a Congregational minister in New Haven, Connecticut, learned of the Amistad’s arrival and decided to publicize the incident to expose the brutalities of slavery and the slave trade. Through evangelical arguments, appeals to higher law, and “moral suasion,” Tappan and his colleagues hoped to launch a massive assault on slavery.

The Amistad incident, Tappan happily proclaimed, was a “providential occurrence.” In his view, slavery was a deep moral wrong and not subject to compromise. Both those who advocated its practice and those who quietly condoned it by inaction deserved condemnation. Slavery was a sin, he declared, because it obstructed a person’s free will inherent by birth, therefore constituting a rebellion against God.

Slavery was also, Tappan wrote to his brother, “the worm at the root of the tree of Liberty. Unless killed the tree will die.”

Tappan first organized the Amistad Committee to coordinate efforts on behalf of the captives, who had been moved to the New Haven jail.

Tappan preached impromptu sermons to the mutineers, who were impressed by his sincerity though unable to understand his language. He wrote detailed newspaper accounts of their daily activities in jail, always careful to emphasize their humanity and civilized backgrounds for a fascinated public, many of whom had never seen a black person. And he secured the services of Josiah Gibbs, a professor of religion and linguistics at Yale College, who searched the docks of New York for native Africans capable of translating Cinqué’s Mende language.

Gibbs eventually discovered two Africans familiar with Mende–James Covey from Sierra Leone and Charles Pratt from Mende itself. At last the Amistad mutineers could tell their side of the story.

Meanwhile, Ruiz and Montes had initiated trial proceedings seeking return of their “property.” They had also secured their government’s support under Pinckney’s Treaty of 1795, which stipulated the return of merchandise lost for reasons beyond human control.

To fend off what many observers feared would be a “judicial massacre,” the abolitionists hired attorney Roger S. Baldwin of Connecticut, who had a reputation as an eloquent defender of the weak and downtrodden.

Baldwin intended to prove that the captives were “kidnapped Africans,” illegally taken from their homeland and imported into Cuba and thus entitled to resist their captors by any means necessary. He argued that the ownership papers carried by Ruiz and Montes were fraudulent and that the blacks were not slaves indigenous to Cuba.

He and his defense team first filed a claim for the Amistad and cargo as the Africans’ property, in preparation for charging the Spaniards with piracy. Then they filed suit for the captives’ freedom on the grounds of humanity and justice: slavery violated natural law, providing its victims with the inherent right of self-defense.

The case then entered the world of politics. It posed such a serious problem for President Martin Van Buren that he decided to intervene. A public dispute over slavery would divide his Democratic party, which rested on a tenuous North-South alliance, and could cost him reelection to the presidency in 1840.

Working through his secretary of state, slaveholder John Forsyth from Georgia, Van Buren sought to quietly solve the problem by complying with Spanish demands.

Van Buren also faced serious diplomatic issues. Failure to return the Africans to their owners would be a violation of Pinckney’s Treaty with Spain. In addition, revealing Spain’s infringement of treaties against the African slave trade could provide the British, who were pioneers in the crusade against slavery, with a pretext for intervening in Cuba, which was a long-time American interest.

The White House position was transparently weak. Officials refused to question the validity of the certificates of ownership, which had assigned Spanish names to each of the captives even though none of them spoke that language. Presidential spokesmen blandly asserted that the captives had been slaves in Cuba, despite the fact that the international slave trade had been outlawed some 20 years earlier and the children were no more than nine years old and spoke an African dialect.

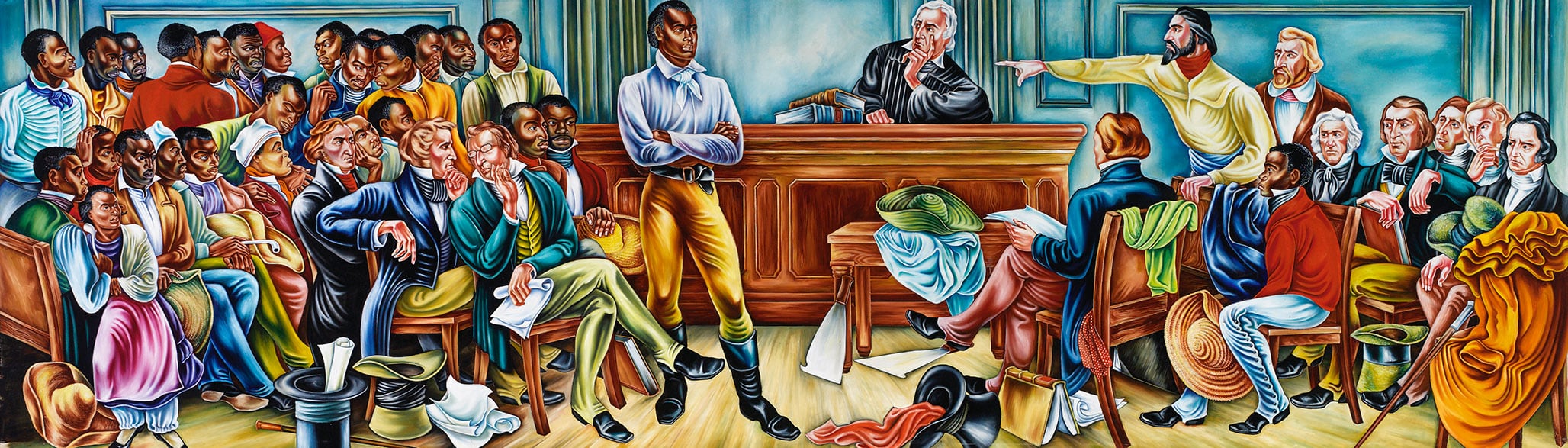

The court proceedings opened on Sept. 19, 1839, amid a carnival atmosphere in the state capitol building in Hartford, Connecticut.

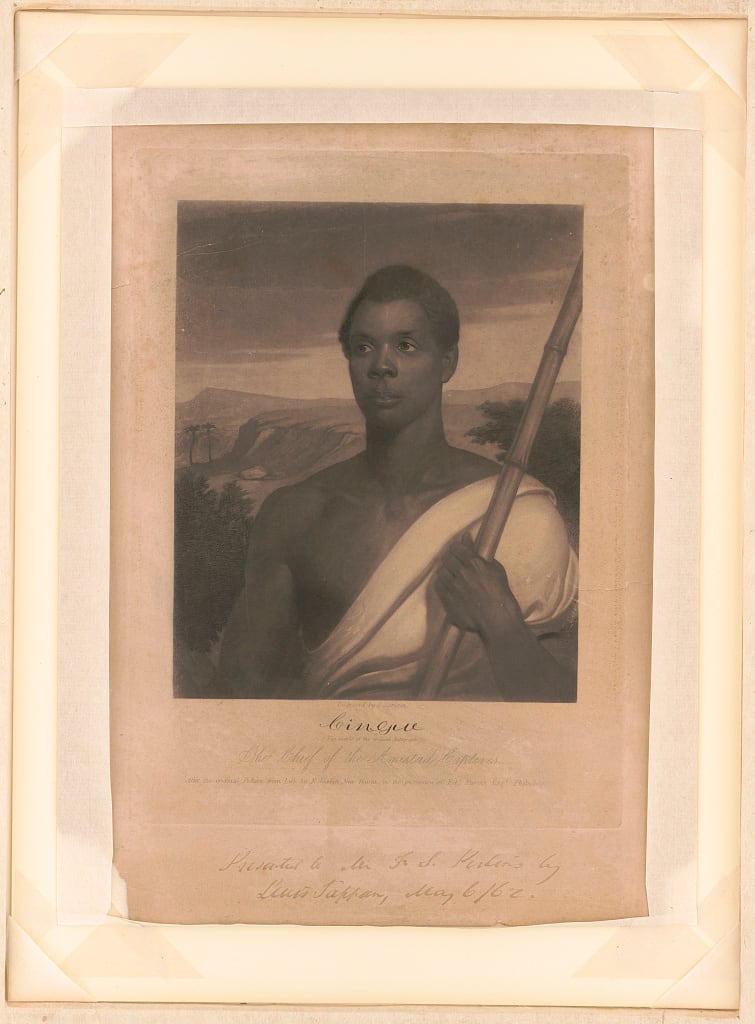

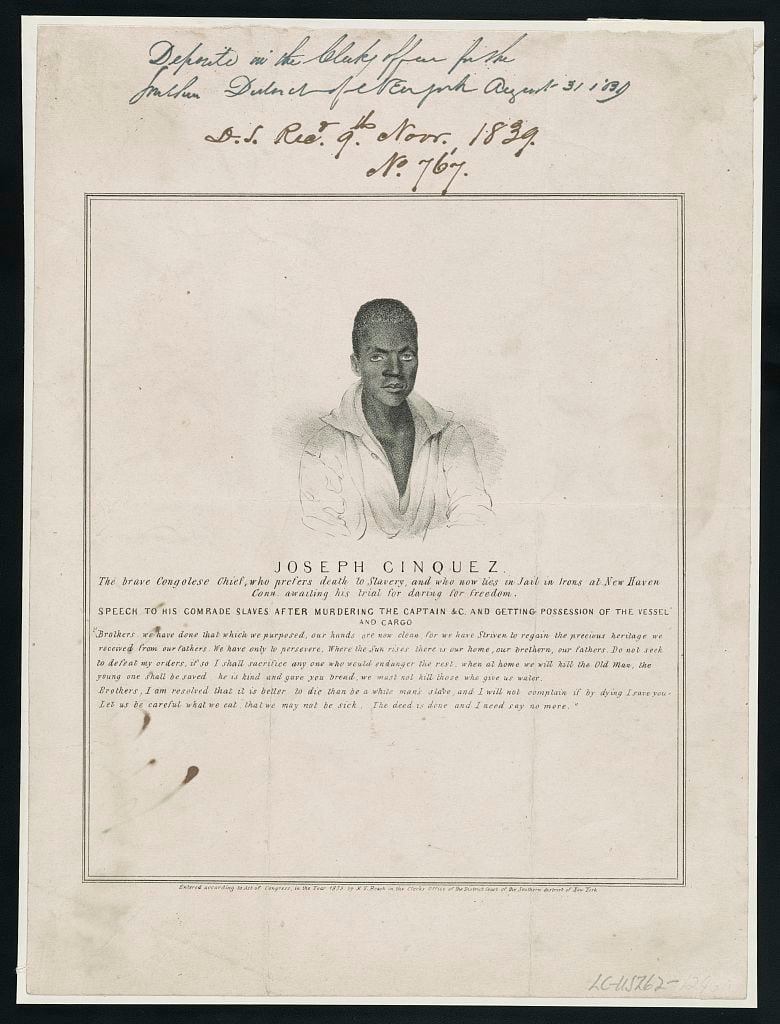

To some observers, Cinqué was a black folk hero; to others he was a barbarian who deserved execution for murder. Poet William Cullen Bryant extolled Cinqué’s virtues, numerous Americans sympathized with the ‘noble savages,’ and pseudo-scientists concluded that the shape of Cinqué’s skull suggested leadership, intelligence, and nobility. The New York Morning Herald, however, derided the “poor Africans,” “who have nothing to do, but eat, drink, and turn somersaults.”

To establish the mutineers as human beings rather than property, Baldwin sought a writ of habeas corpus aimed at freeing them unless the prosecution filed charges of murder. Issuance of the writ would recognize the Africans as persons with natural rights and thus undermine the claim by both the Spanish and American governments that the captives were property. If the prosecution brought charges, the Africans would have the right of self-defense against unlawful captivity; if it filed no charges, they would go free. In the meantime, the abolitionists could explore in open court the entire range of human and property rights relating to slavery.

As Leavitt later told the General Antislavery Convention in London, the purpose of the writ was “to test their right to personality.”

Despite Baldwin’s impassioned pleas for justice, the public’s openly expressed sympathy for the captives, and the prosecution’s ill-advised attempt to use the four black children as witnesses against their own countrymen, Associate Justice Smith Thompson of the U.S. Supreme Court denied the writ.

Thompson was a strong-willed judge who opposed slavery, but he even more ardently supported the laws of the land. Under those laws, he declared, slaves were property. He could not simply assert that the Africans were human beings and grant freedom on the basis of natural rights. Only the law could dispense justice, and the law did not authorize their freedom. It was up to the district court to decide whether the mutineers were slaves and, therefore, property.

Prospects before the district court in Connecticut were equally dismal. The presiding judge was Andrew T. Judson, a well-known white supremacist and staunch opponent of abolition. Baldwin attempted to move the case to the free state of New York on the grounds that Gedney had seized the Africans in that state’s waters and not on the high seas. He hoped, if successful, to prove that they were already free upon entering New York and that the Van Buren administration was actually trying to enslave them.

But Baldwin’s effort failed; the confrontation with Judson was unavoidable.

Judson’s verdict in the case only appeared preordained; as a politically ambitious man, he had to find a middle ground.

Whereas many Americans wanted the captives freed, the White House pressured him to send them back to Cuba. Cinqué himself drew great sympathy by recounting his capture in Mende and then graphically illustrating the horrors of the journey from Africa by sitting on the floor with hands and feet pulled together to show how the captives had been packed into the hot and unsanitary hold of the slave vessel.

The Spanish government further confused matters by declaring that the Africans were both property and persons. In addition to calling for their return as property under Pinckney’s Treaty, it demanded their surrender as “slaves who are assassins.”

The real concern of the Spanish government became clear when its minister to the United States, Pedro Alcántara de Argaiz, proclaimed that “The public vengeance of the African Slave Traders in Cuba had not been satisfied.”

If the mutineers went unpunished, he feared, slave rebellions would erupt all over Cuba.

Argaiz’s demands led the Van Buren administration to adopt measures that constituted an obstruction of justice. To facilitate the Africans’ rapid departure to Cuba after an expected guilty verdict, Argaiz convinced the White House to dispatch an American naval vessel to New Haven to transport them out of the country before they could exercise the constitutional right of appeal.

By agreeing to this, the president had authorized executive interference in the judicial process that violated the due-process guarantees contained in the Constitution.

Judson finally reached what he thought was a politically safe decision.

On Jan. 13, 1840, he ruled that the Africans had been kidnapped, and, offering no sound legal justification, ordered their return to Africa, hoping to appease the president by removing them from the United States. Six long months after the mutiny, it appeared that the captives were going home.

But the ordeal was not over. The White House was stunned by the decision: Judson had ignored the “great [and] important political bearing” of the case, complained the president’s son, John Van Buren.

The Van Buren administration immediately filed an appeal with the circuit court. The court upheld the decision, however, meaning that the case would now go before the U.S. Supreme Court, where five of the justices, including Chief Justice Roger Taney, were southerners who were or had been slave owners.

Meanwhile, the Africans had become a public spectacle. Curious townspeople and visitors watched them exercise daily on the New Haven green, while many others paid the jailer for a peek at the foreigners in their cells. Some of the most poignant newspaper stories came from professors and students from Yale College and the Theological Seminary who instructed the captives in English and Christianity.

But the most compelling attraction was Cinqué. In his mid-twenties, he was taller than most Mende people, married with three children, and, according to the contemporary portrait by New England abolitionist Nathaniel Jocelyn, majestic, lightly bronzed, and strikingly handsome. Then there were the children, including Kale, who learned enough English to become the spokesperson for the group.

The supreme court began hearing arguments on February 22, 1841. Van Buren had already lost the election, partly, and somewhat ironically, because his Amistad policy was so blatantly pro-South that it alienated northern Democrats.

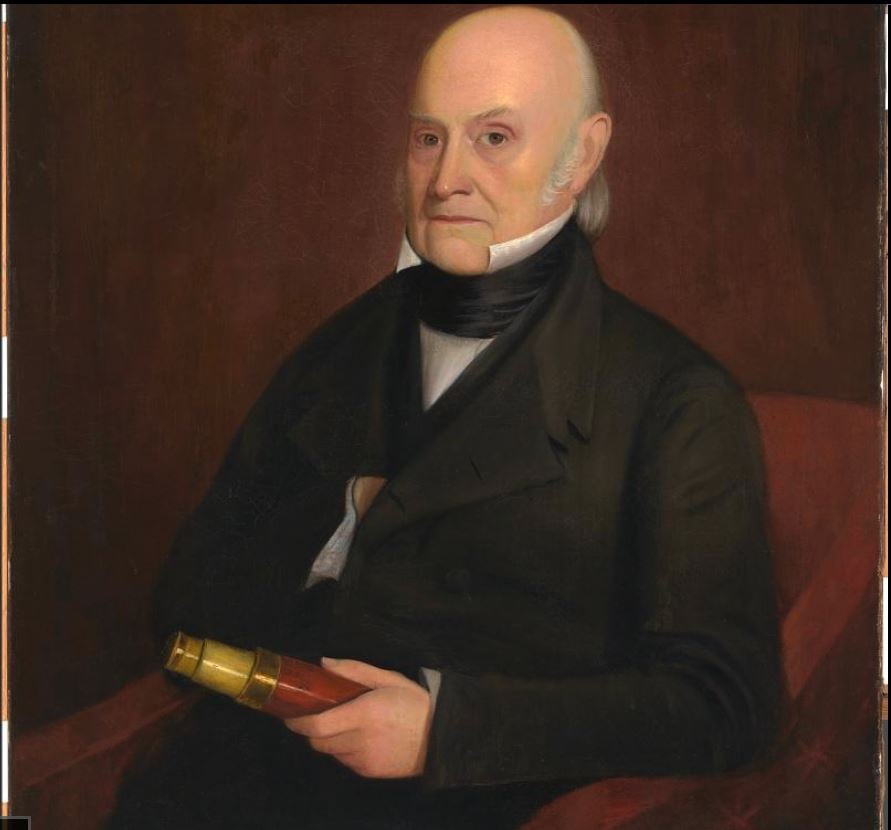

The abolitionists wanted someone of national stature to join Baldwin in the defense and finally persuaded former President John Quincy Adams to take the case even though he was 73 years old, nearly deaf, and had been absent from the courtroom for three decades. Now a congressman from Massachusetts, Adams was irascible and hard-nosed, politically independent, and self-righteous to the point of martyrdom.

He was fervently antislavery, though not an abolitionist, and had been advising Baldwin on the case since its inception. His effort became a personal crusade when the young Kale wrote him a witty and touching letter, which appeared in the Emancipator and concluded with the ringing words, “All we want is make us free.”

Baldwin opened the defense before the Supreme Court with another lengthy appeal to natural law, then gave way to Adams, who delivered an emotional eight-hour argument that stretched over two days. In the small, hot, and humid room beneath the Senate chamber, Adams challenged the Court to grant liberty on the basis of natural rights doctrines found in the Declaration of Independence.

Pointing to a copy of the document mounted on a huge pillar, he proclaimed that, “I know of no other law that reaches the case of my clients, but the law of Nature and of Nature’s God on which our fathers placed our own national existence.”

The Africans, he proclaimed, were victims of a monstrous conspiracy led by the executive branch in Washington that denied their rights as human beings.

Adams and Baldwin were eloquent in their pleas for justice based on higher principles. As Justice Joseph Story wrote to his wife, Adams’s argument was “extraordinary … for its power, for its bitter sarcasm, and its dealing with topics far beyond the records and points of discussion.”

On March 9, Story read a decision that could not have surprised those who knew anything about the man.

An eminent scholar and jurist, Story was rigidly conservative and strongly nationalistic, but he was as sensitive to an individual’s rights as he was a strict adherent to the law. Although he found slavery repugnant and contrary to Christian morality, he supported the laws protecting its existence and opposed the abolitionists as threats to ordered society. Property rights, he believed, were the basis of civilization.

Even so, Story handed down a decision that freed the mutineers on the grounds argued by the defense. The ownership papers were fraudulent, making the captives “kidnapped Africans” who had the inherent right of self-defense in accordance with the “eternal principles of justice.”

Furthermore, Story reversed Judson’s decision ordering the captives’ return to Africa because there was no American legislation authorizing such an act. The outcome drew Leavitt’s caustic remark that Van Buren’s executive order attempting to return the Africans to Cuba as slaves should be ‘engraved on his tomb, to rot only with his memory.’

The abolitionists pronounced the decision a milestone in their long and bitter fight against the “peculiar institution.”

To them, and to the interested public, Story’s “eternal principles of justice” were the same as those advocated by Adams. Although Story had focused on self-defense, the victorious abolitionists broadened the meaning of his words to condemn the immorality of slavery.

They reprinted thousands of copies of the defense argument in pamphlet form, hoping to awaken a larger segment of the public to the sordid and inhumane character of slavery and the slave trade. In the highest public forum in the land, the abolitionists had brought national attention to a great social injustice.

For the first and only time in history, African blacks seized by slave dealers and brought to the New World won their freedom in American courts.

The final chapter in the saga was the captives’ return to Africa. The abolitionists first sought damage compensation for them, but even Adams had to agree with Baldwin that, despite months of captivity because bail had been denied, the “regular” judicial process had detained the Africans, and liability for false imprisonment hinged only on whether the officials’ acts were “malicious and without probable cause.”

To achieve equity, Adams suggested that the federal government finance the captives’ return to Africa. But President John Tyler, himself a Virginia slaveholder, refused on the grounds that, as Judge Story had ruled, no law authorized such action.

To charter a vessel for the long trip to Sierra Leone, the abolitionists raised money from private donations, public exhibitions of the Africans, and contributions from the Union Missionary Society, which black Americans had formed in Hartford to found a Christian mission in Africa.

On Nov. 25, 1841, the remaining 35 Amistad captives, accompanied by James Covey and five missionaries, departed from New York for Africa on a small sailing vessel named the Gentleman. The British governor of Sierra Leone welcomed them the following January — almost three years after their initial incarceration by slave traders.

The aftermath of the Amistad affair is hazy.

One of the girls, Margru, returned to the United States and entered Oberlin College, in Ohio, to prepare for mission work among her people. She was educated at the expense of the American Missionary Association (AMA), established in 1846 as an outgrowth of the Amistad Committee and the first of its kind in Africa.

Cinqué returned to his home, where tribal wars had scattered or perhaps killed his family. Some scholars insist that he remained in Africa, working for some time as an interpreter at the AMA mission in Kaw-Mende before his death around 1879.

No conclusive evidence has surfaced to determine whether Cinqué was reunited with his wife and three children, and for that same reason there is no justification for the oft-made assertion that he himself engaged in the slave trade.

The importance of the Amistad case lies in the fact that Cinqué and his fellow captives, in collaboration with white abolitionists, had won their freedom and thereby encouraged others to continue the struggle.

Positive law had come into conflict with natural law, exposing the great need to change the Constitution and American laws in compliance with the moral principles underlying the Declaration of Independence.

In that sense the incident contributed to the fight against slavery by helping to lay the basis for its abolition through the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution in 1865.

RELATED

This article by Dr. Howard Jones originally appeared in the January/February 1998 issue of American History Magazine, a sister publication of Navy Times. Jones is the author of numerous books, including Mutiny on the Amistad: The Saga of a Slave Revolt and Its Impact on American Abolition, Law, and Diplomacy, published by Oxford University Press. For more great articles, be sure to pick up your copy of American History.