San Diego — Dozens of U.S. Navy officials have admitted to being bought off by the gregarious, rotund Malaysian defense contractor known as “Fat Leonard” who plied them with prostitutes, Cuban cigars and free stays at the Philippines’ Shangri-La hotel, among other things.

Now as the last five of 34 defendants stand trial in federal court in San Diego, what’s more shocking is how little the case has changed the Navy’s way of doing business, according to former military officers and government watchdog advocates.

RELATED

“You would expect that one of the largest corruption scandals in the history of the United States Navy would provoke pretty dramatic changes to prevent something like this from happening again in the future. But sadly, that’s not really the case,” said Dan Grazier, a former Marine who now works as a military analyst at the Project on Government Oversight in Washington.

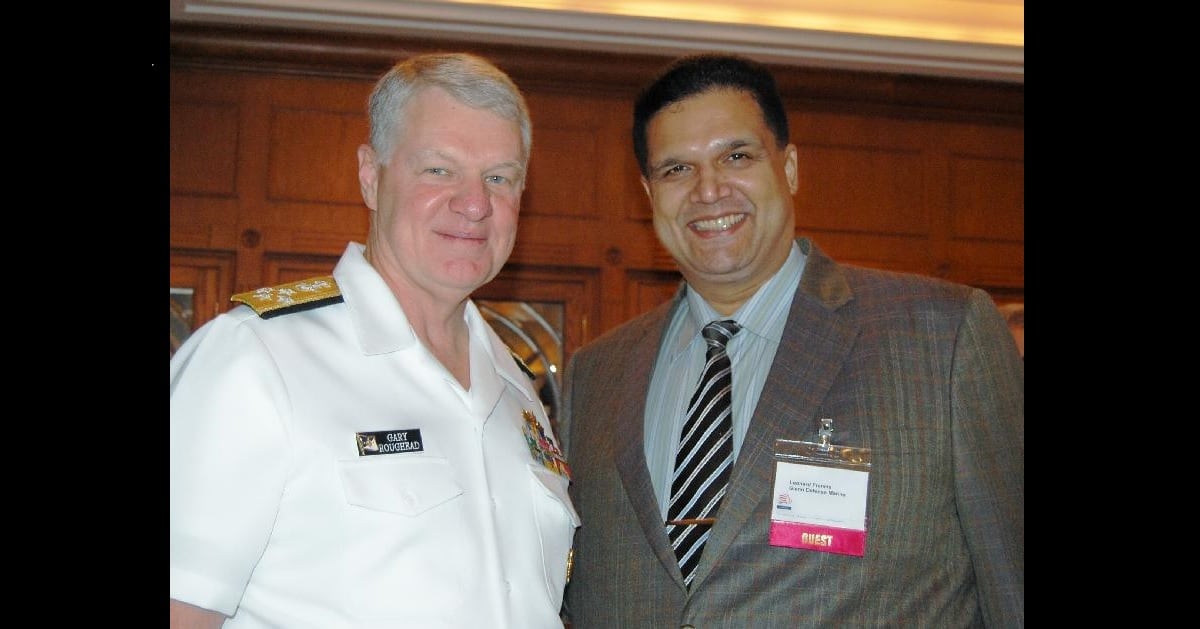

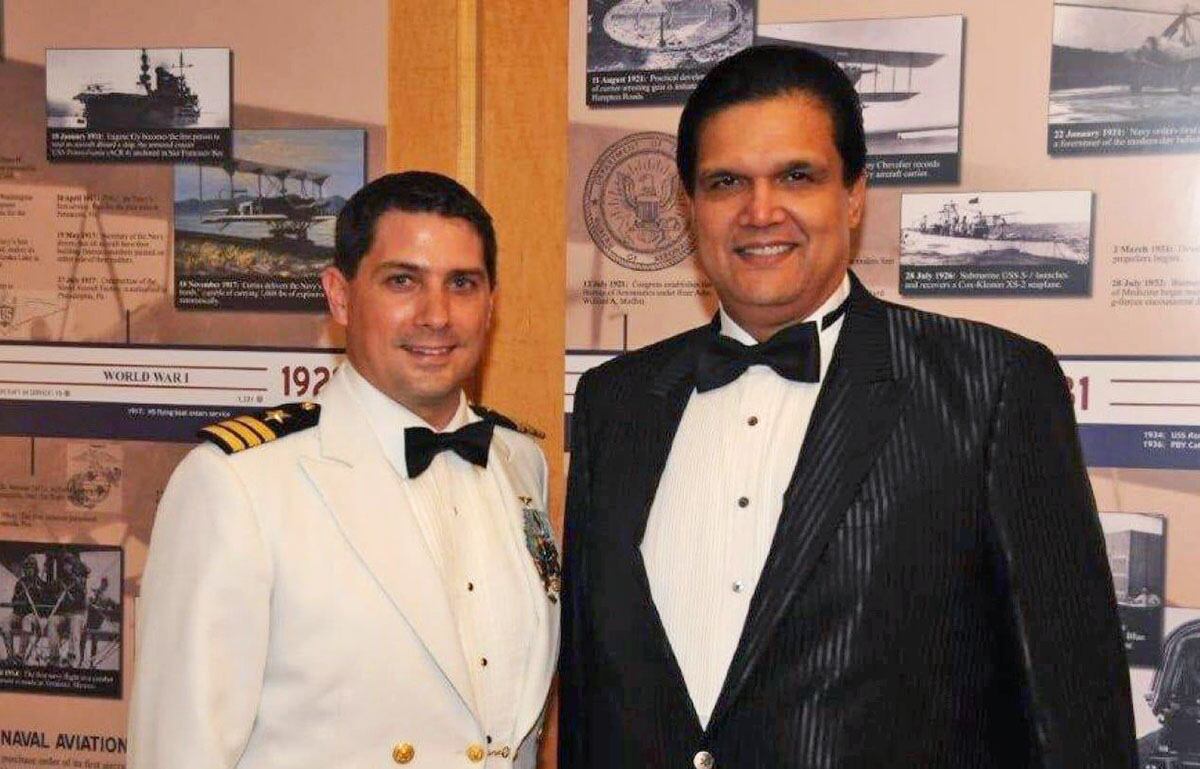

The case has centered around Leonard Glenn Francis who admitted in 2015 to offering $500,000 in bribes to Navy officers. In exchange, the officers passed him classified information and even went so far as redirecting military vessels to ports that were lucrative for his Singapore-based ship servicing company, Glenn Defense Marine Asia, or GDMA.

Twenty-nine people, mostly Navy officials, have pleaded guilty to helping Francis including providing classified ship schedules in exchange for extravagant outings in South Asia with prostitutes and meals with tabs totaling more than $20,000.

“While scores of Navy officials were partying with Leonard Francis, a massive breach of national security was in full swing,” U.S. Attorney Randy Grossman said recently.

Prosecutors say Francis and his company overcharged the U.S. military by more than $35 million for its services between 2004 and 2013, which included providing food and water to the ships at Pacific ports in Asia.

Francis, who is scheduled to be sentenced in July, has been cooperating with the U.S. Department of Justice since his arrest in 2013 in San Diego.

RELATED

Five officers — Rear Adm. Bruce Loveless, Capts. David Newland, James Dolan and David Lausman, and Cmdr. Mario Herrera — have maintained their innocence and have gone to trial.

It’s unclear whether Francis, who is in poor health and has been under house arrest, will testify at the trial, which is expected to last months. Defense lawyers have been trying to prevent him from taking the stand after he gave his version of events in a podcast last year.

Navy officials vowed to clean up their contracting processes in response to the scandal and implemented more oversight. Sailors received more ethics training. Supply officers have less independence. Goods and services now must be priced at current market rates as determined by the Navy’s Fleet Logistics Centers.

But that’s not enough for Grazier, who said the military needs to move away from contracting out so much of its work. As bases have closed worldwide, the Navy has increasingly turned to contractors to do what it once did in-house.

“I think unless the Navy really changes the way it does business, future Fat Leonards are just going to be more cautious, but it’s not going to change their practices,” Grazier said.

Grazier fears the case’s biggest impact has been on young people like his son who is an enlisted sailor.

“They think they’re signing up for something really noble, and then they see all these people that they’re supposed to look up to behaving in such an unethical and often times illegal fashion,” Grazier said. “That’s hugely crushing for these young idealists. I think that’s one of the biggest tragedies of all this.”

Craig Hooper, a defense contractor, said the Navy needs to increase its auditing teams and also adapt its rules so they fit the cultural norms of where it operates.

In Asia, for instance, it’s common to go out for drinks or dinner to form business relationships yet many junior officers are expected to pay out of their own pockets, though many can’t afford it. Hooper said the Navy should be footing those bills rather than creating situations that lend themselves to corruption.

Bryan Clark, a fellow at the Hudson Institute, said the Navy’s brass has also long turned a blind eye to contractors who might be unscrupulous but who could get things done. When he was a sailor in the Pacific more than 20 years ago, it was known then Francis was “sleazy,” but he was also well-connected in the region, he said.

He hopes the case will teach officers that those things can no longer be ignored, though he said it’s unfortunate that many high-ranking officers who were investigated got off with early retirements while lower-ranking officers were charged.

“It’s just a huge black eye for the Navy from a cultural perspective and a legal perspective,” Clark said. “Because it wasn’t just, you know, a couple of bad apples.”