Retired Army Col. Fred Hart is trying to ensure that his fellow military comrades who lived through a harrowing chapter in American history more than three decades ago can get POW status and benefits.

Few Americans know that when Iraq invaded Kuwait in August 1990, 16 service members — and, in some cases, their families — were held hostage, trapped in the American embassy in Kuwait and then taken to the embassy in Iraq. Now, shortly after National POW/MIA Recognition Day, Hart is on a mission to ensure they receive recognition of their ordeal and to let them know they can apply for former POW status and the significant benefits that come with it.

The anxiety Hart felt in those darks days came flooding back as he watched the chaos of the Afghanistan withdrawal unfolding in August 2021.

Then, in April 2022, nearly 32 years after the Iraqi invasion, Hart received a short letter from the Army notifying him that he had been awarded Prisoner of War status — 13 years after he requested it for himself and his 15 Army, Marine and Navy comrades. The Army says his original request was sent to the wrong department, after Hart addressed it to the secretary of the Army in 2009.

But the saga — and Hart’s mission — isn’t over.

Hart is now dealing with the Army’s refusal to notify his comrades that they, too, may qualify for POW status.

“It is my hope that our story of unwavering support to the U.S. Embassy and CENTCOM mission before, during and after the Iraqi invasion will obtain the recognition and award of the POW medal” to all the service members involved, Hart said.

Iraq let family members leave the country in late August 1990, though it kept the U.S. service members in Baghdad. The family members then traveled overland by convoy all the way to Turkey. But once they returned to U.S. soil, they had to fight to get their military medical and other benefits restored because they had destroyed their military IDs and other documents in Kuwait in an attempt to keep their military identities secret.

Two months later, Hart and a few others — who were confined to the U.S. Embassy — were tapped to participate in a risky, but successful escape. The other service members were among the hostages Iraq released in December, weeks before Operation Desert Storm began in January 1991.

Since receiving that letter in April, Hart has received his Prisoner of War Medal, which is only awarded when an individual’s POW status has been officially confirmed and recognized as such by the Department of the Army.

He would like his fellow service members to get the medals as well, but his greater concern is that they receive the VA benefits that accrue to former POWs. It is important, he said, because “several members had suffered various mental and physical conditions related to our hostage situation.” He has stayed in contact with some, and has spent a lot of time trying to reach the others to provide information about applying for the status, but has been unsuccessful in reaching everyone.

Seven of his fellow service members have applied for and received POW status since he got his letter in April. That includes the widow of CW3 Gene Lord, who received her late husband’s POW status posthumously, Hart said, and will receive benefits associated with that.

In the years following the incident, the Army classified the soldiers involved as “beleaguered.” When it finally granted his request for POW status, with little explanation, Hart asked Army officials for help in reaching all the soldiers, but they have refused.

Army officials told Military Times they don’t currently have a requirement to notify soldiers and veterans that they may be eligible for POW status. The status must be requested by the individual through the Army Human Resources Command. Officials declined to comment on whether any of the other soldiers have been awarded the POW status, citing privacy issues.

Hart said he is dismayed by this stance. “It’s amazing. When the government wants something out of you, they can find you,” he said.

He contacted Military Times in a last-ditch effort to reach the other service members.

Then-Cpl. Paul Rodriguez, one of the Marines serving in Kuwait, was awarded POW status separately by the Department of Veterans Affairs. Information was not available from Marine Corps officials about the process for Marines to apply for the status through the Marine Corps.

There was one sailor in the group, Ray Galles, a chief petty officer. A Navy spokesman said the Navy “has no way of contacting retired sailors,” and added that their record check showed no indication Galles had received POW status. The best step for the veteran would be to file a petition with the Board for Corrections of Naval Records, the spokesman said. More information can be found at the Navy human resources site. Marines can also use the process outlined there.

“There are a lot of benefits from the VA and from states” for former prisoners of war, Hart said. That includes certain presumptive medical conditions. If a former POW is diagnosed as having one or more of these conditions to a degree that is at least 10 percent disabling, VA presumes that it is associated with the POW experience. More than 16,000 POWs are receiving disability compensation for service-connected injuries, diseases or illnesses, according to the VA.

Former POWs are also eligible for VA health care. This includes hospital, outpatient and nursing home care, and Hart said he knows some of his comrades could especially benefit.

Some states offer benefits to former POWs, but they vary by state.

The service members who were with Hart in Kuwait when the Iraqis invaded on Aug. 2, 1990 are:

Army: Col. John Mooneyham; Lt. Col. Tom G. Funk; Lt. Col. Rhoi Maney; Capt. Bill Schultz; CW4 Dave Forties; CW3 Gene Lord; Master Sgt. Alfred Allen, and Sgt. 1st Class Laurens Vellekoop.

Navy: Chief Petty Officer Ray Galles.

Marine Corps: Gunnery Sgt. Jim Smith; Sgt. Gerald Andre; Cpl. Dan Hudson; Cpl. Paul Rodriguez; Cpl. Mark Royer, and Cpl. Mark Ward.

Why did it take 13 years?

In 2009, Hart requested POW status for all the military members who were in Kuwait, in letters to the secretary of the Army and the secretary of the Navy. He got no response.

In 2021, he sent another letter to the Army, after doing more research. And the Army awarded him POW status the following April.

Nothing had changed in policy or law since 2009, Army officials said. His original request was simply routed to the wrong department.

“It appears that Mr. Hart’s original request in 2009 … was sent to the wrong department and therefore, could not be processed,” officials stated. “[Human Resources Command] Awards and Decorations did not receive Mr. Hart’s request until January 2022 and approved it in April 2022.”

Hart found that perplexing.

“You figure if you send it to a high-level office, it would be sent to the right office,” he said, adding that he knows of at least one soldier who could have benefited from VA medical care.

Read about the Harts’ ordeal in Kuwait in Military Times’ 1993 story:

Trying times

The affected troops, members of the United States Liaison Office Kuwait and the U.S. Marine Corps Embassy Security Detachment, were frustrated as they witnessed the run-up to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, “and nobody listened to us,” Hart said. Two weeks before the invasion, their colonel asked the U.S. ambassador to send the families out of Kuwait.

“They said they didn’t want to send the wrong message to the Kuwaitis,” Hart said. “They were convinced it wasn’t going to happen … even when we told them the Iraqis were on the border.”

One of the soldiers, CW4 Dave Forties, took about 10 rolls of film of the Iraqis as they swept in, and the soldiers wrote pages of notes. “We could identify all the Iraqi anti-aircraft locations, because they all had beach umbrellas,” Hart said. Yet there was no debriefing by the Army when they returned to the U.S., before Operation Desert Storm began, although the CIA did debrief them. The service members weren’t given medical evaluations.

Hart has written a detailed account of the events for the Army War College.

“I thought it was important for my daughters and important information for the Army,” he said. One reason he wrote the paper was to let the Army know that when a service member is detained in such situations, there need to be procedures in place to help the service member, and families, during that time and afterward.

The families’ troubles continued after they reached American soil. The wives faced innumerable obstacles getting any military benefits, because they had trouble proving their identity. This included medical care, housing, pay and relocation pay. They also fought to be reimbursed for all their household goods that were lost.

“Even after everyone and their families were returned to the United States, their struggles to get assistance and support was a constant challenge,” Hart said.

To be fair, Hart said, military officials “were focused on getting the war together.”

“But even immediately following Desert Storm both the Army and U.S. Central Command had little interest in obtaining valuable lessons learned from a military experience during a chaotic crisis very akin to the recent debacle in Afghanistan,” Hart said.

Without a doubt, he said, American officials could have learned lessons from what happened to the Americans in Kuwait.

Indeed, most Americans don’t know there were Americans trapped in Kuwait — including military families, State Department personnel and their families and others — when Saddam Hussein’s Iraqi forces invaded on Aug. 2, 1990.

The families saw Iraqi tanks rolling down the highway near their apartments, and heard shells hitting all around them. For six days, the families holed up in their houses, trying to prepare for the worst.

“It was just terrifying, especially in the first couple of days of the invasion, when you had artillery, Iraqi troops roaming around, machine gun fire, wrecked cars, fires,” Hart said.

“All you could think of was trying to protect your family first and foremost. Then to be left out there with the embassy in absolute pandemonium. … How am I going to get my family to the embassy when we’ve got Republican Guard all up and down the road?

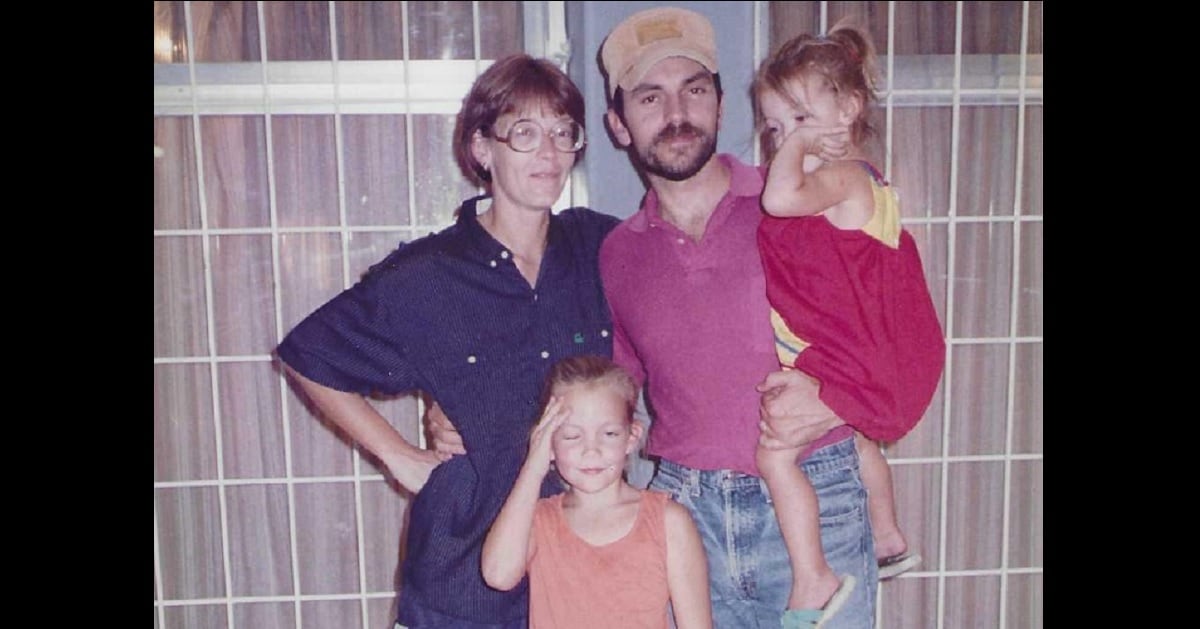

“At any time they could have grabbed my wife and kids. My wife, Chris, was terrified because Natasha was a blond-haired little girl. And I probably would have been killed.”

Watching the hasty withdrawal from Afghanistan unfolding in August, 2021, Hart and some of his former comrades were talking. “We all had the same feeling. We were getting that same anxiety,” he said.

They drew parallels with their situation. “In Kuwait, we were literally out on the economy, and they were saying to come in to the embassy. We were saying, ‘Have you seen the roads out there, full of burned vehicles and Iraqi checkpoints? You want us to put our wives and kids in a car and just drive into who knows what?’ " Hart said.

“We watched Afghanistan, and it was the same thing: ‘Oh yes, they can get into the airport.’

“They had no idea.”

The long road to safety

After days of fear and uncertainty, the U.S. Embassy in Kuwait on on Aug. 7, 1990, sent a car to take families from their residences to the compound — a frightening ride, especially for the children, who could see Iraqi soldiers, tanks and smoke from the charred remains of vehicles all along the way.

For 16 days, the families were stuck in the embassy compound. Chris Hart and a State Department wife cooked for 175 people, three times a day, on four burners. Others took on other tasks, such as organizing structured play for the children.

Fred Hart and other men sneaked out to forage for food, running the gauntlet of Iraqi roadblocks. They grew beards to camouflage their American appearance. Hart credits CW4 Dave Forties for his skill and courage in operating the alleyways and back roads of Kuwait, and later, Baghdad, in search of food and supplies.

While the embassy walls gave them some sense of security, bullets continually zinged over them and they all knew that at any second, the Iraqis could come inside and take them.

“It was surreal,” Hart said. They constantly searched for any news, “listening to anything we could to make sure we were still on the radar screen and that the government was going to do something to get us out.”

But, he said, “there was no way CENTCOM could come in and rescue us, because you’ve got the Kuwait International Hotel, 17 floors, right over the embassy. The whole Iraqi army had taken over the entire hotel. They were all up there with their guns, looking down on the embassy, right over us.”

Bombing the Kuwait International Hotel was not an option, because it would have likely damaged the embassy, too, he said.

In the early hours of Aug. 23, 1990, the Iraqis agreed to let the Americans go to Jordan — but they had to go to Baghdad first. Their convoy trekked across the desert. Young Mary Hart, 2, was sick with diarrhea, and dehydrated, and she wouldn’t eat or drink. Her mother kept pouring water over her. Arriving at the U.S. embassy in Baghdad the families were told they’d be leaving for Jordan in a few hours, but those hours turned into days, and their destination changed to Turkey.

The Iraqis allowed the women and children to leave Aug. 26, but the men had to stay behind.

The normal six-hour drive to Turkey took the women and children a grueling 21 hours, in part due to Iraqi harassment and stall tactics, and a six-hour wait at the Turkish border. Chris Hart was driving one of the embassy armored vehicles, and 7-year-old Natasha was tasked with changing her 2-year-old sister’s diapers during the trip.

The men were forced to stay behind at the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad, and the Iraqi secret police took up residence across the street, watching their every move. The military members took great pains to keep their identity as military members secret, including being careful about what they discarded in the trash.

“Our daily status was in grave peril, our mental anguish, poor diet, general conditions, and constant Iraqi threats of death, beatings, torture and intimidation was of such serious concern that Department of Defense encouraged, and authorized, members to participate in escape planning,” wrote Hart, in his June, 2009 letter requesting consideration for POW status.

In October 1990, Hart and a few others were told they would be part of an escape attempt, carried out by Polish nationals through numerous Iraqi checkpoints. “It was quite a remarkable operation. A lot of risks were involved, moving through another country, using another identity and falsified documents,” he said.

The escape was a test, to see if a similar operation could rescue the others later. That risky, successful escape wasn’t publicized or revealed, in order to avoid exposing anyone who helped them, and not to spoil any other planned escapes, Hart said.

But by early December, the Iraqis decided to allow all Western hostages to leave Iraq and Kuwait. Others in their group were allowed to leave by about Dec. 20, 1990, after 140 days as virtual captives.

The secrecy surrounding the ordeal is part of the reason the service members have had difficulty with red tape.

‘It’s always there’

“Still, after 32 years, it comes back. I won’t say it haunts you, but it’s always there,” Hart said.

“The biggest trigger is the news, like Afghanistan. Any time you see refugees, war, it comes back.”

While he doesn’t have post-traumatic stress, he said, the situation of seeing Americans being left behind in Afghanistan has been difficult for him and his family. “It made me so mad,” he said, adding that his daughter Natasha told him she couldn’t watch the events on TV.

Hart is glad the Army awarded him POW status, but says all the service members involved deserve it.

“With this recognition, another chapter can close in a saga that has endured for the past 30 years.”

Karen has covered military families, quality of life and consumer issues for Military Times for more than 30 years, and is co-author of a chapter on media coverage of military families in the book "A Battle Plan for Supporting Military Families." She previously worked for newspapers in Guam, Norfolk, Jacksonville, Fla., and Athens, Ga.