WASHINGTON — The U.S. Navy will prioritize readiness and sustainment in this new fiscal year, the acting Navy acquisition chief told Defense News.

Fiscal 2022 is starting under a continuing resolution that won’t allow new programs to start or procurement quantities to increase — but Jay Stefany, acting assistant secretary of the Navy for research, development and acquisition (ASN RDA), said that’s not as problematic for the Navy this year as it was in previous years.

Most of the aviation programs, he said, are either well into a production line or in sustainment. The Navy’s shipbuilding plan largely mirrors last year’s. Congress is still weighing how many of each class of ship to buy, but the Navy isn’t planning to start new ship programs.

Asked about his greatest concern under the continuing resolution, Stefany said he’s “always worried about Columbia [ballistic missile submarine], although I don’t think it needs money in the first two months.”

“But if we get to a second CR, I think we would have to do something there,” he added.

There are so few new programs this year that, when asked about a list of anomalies the Navy would send to congressional appropriators — which are used to pursue exceptions to CR rules and allow new programs to start or grow in quantity — Stefany said: “For the first CR, it’s not a long list. If there is a second CR, that would be a different story.”

Rather, FY22 will emphasize sustainment and paving the way for future readiness.

Stefany said that fiscal year will be critical for the Navy’s Shipyard Infrastructure Optimization Program, which was originally pitched as a 20-year, $21 billion effort to make the four public naval repair yards more modern and efficient.

Stefany said this is a once-in-a-century effort. By the end of FY22, the service will have mapped out the “tactical part and figure out how it’s all going to work.”

The Navy is creating 3D models of all four yards and using those digital twins to test ideas for new layouts. The technology allows the service to run multiple iterations of yard designs, weighing which yield the best results for efficiently moving materials through the yard, shielding workers from the elements, leveraging new technologies to build ships faster and more.

The four digital twins should be done by the end of December 2021, he said. Using that information, the Navy will develop area plans that will show what the redesigned yards look like and address environmental issues, among others.

“That’s really one big focus area for the coming year, is going from the ‘Yeah, we think we can make it more optimal’ to the ‘Yeah, here’s an actual optimization plan for this shipyard, let’s go do it,’ ” Stefany said.

Dry dock upgrades will happen in parallel, he added, after the Navy recently awarded $1.3 billion and then another $63 million to improve dry docks at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Maine, as well as a $500 million contract to support early projects at Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard and the Intermediate Maintenance Facility in Hawaii as well as Puget Sound Naval Shipyard and the Intermediate Maintenance Facility in Washington.

The dry docks need upgrades because they’re aging, and because new platforms like the Ford-class aircraft carrier and the Block V Virginia-class attack submarine are too large or require more power and cooling capabilities than what the docks can handle.

But the digital twins will lead to a more revolutionary change in how shipyard work is performed and the tools that are used, he said.

Stefany also said FY22 will involve early work on upcoming multiyear procurement contracts. The Navy plans to prepare a contract for the Arleigh Burke-class destroyer program that will span from FY23 to FY27. The Navy previously planned to build these DDG-51s through FY22 and then move into the DDG(X) follow-on program. But with that next-generation combatant program struggling to define its requirements, the Navy will use another DDG-51 multiyear contract to buy more time and keep the industrial base stable until the transition is made later in the decade.

The Navy acquisition community will also start work on a Virginia Block VI contract for FY24 to FY28. While the DDG contract would include the same Flight III design under construction today, each block of Virginia submarines has included capability upgrades and manufacturing improvements, requiring more design work ahead of competing and awarding a multiyear contract.

Additionally, the Navy and Marine Corps need to develop a contract for the CH-53K heavy-lift helicopter that could cover five or six years of helo procurement, he said.

In addition to serving as Navy acquisition chief, Stefany fills the role of the Pentagon’s F-35 Joint Strike Fighter service acquisition executive, a job that alternates between the Navy and the Air Force, but is currently assigned to the former.

Last month, the Pentagon signed a contract with Lockheed Martin that laid out jet sustainment plans. The $6.6 billion contract covers sustainment through FY23 for American and international customers, and the deal would reduce the program’s cost per flying hour.

Stefany said he’ll track the early execution of that sustainment to make sure the contract is working as intended — to keep F-35 readiness up and costs down for the Navy, Marine Corps and Air Force.

Additionally, the F-35 program has struggled with the Block IV technology development effort that, primarily through software upgrades, is meant to allow the jets to use more weapons as well as improve their sensors and warfare systems, among other features. Stefany said the program will move past those issues in FY22.

“In the coming six months or so, I think we’re going to see some predictable performance going forward. It may not be recovering to the old plan, but I think we’ll get to a place where ... those upgrades are going to come through, [where] we can predict it, and [where] we and the partners can plan on this capability at this time on that aircraft tail number,” he said.

In a major behind-the-scenes effort, the Navy and Marine Corps spent the last six months upgrading their networks. Almost everyone previously using the Navy-Marine Corps Intranet, which accounts for about two-thirds of their personnel, has transitioned to Microsoft Office 365, Stefany said. The other one-third uses special networks, including one solely dedicated for strategic systems programs and another for the fleet. Next year, those personnel will also move to Microsoft Office.

“While not as exciting as ships and missiles and that kind of stuff, getting the business all in the same environment from a network and computing environment is another big area that’s … very important to get all of us acting as one Navy/Marine Corps from a business point of view,” Stefany said.

All relevant parties should be transitioned to Microsoft Office by the fall or winter of 2022. Once that happens, the old networks can be turned off, “and besides getting a better integrated product for the team, we can start saving money on all those legacy programs, networks, that are out there,” he added.

Overarching priorities

Stefany was named acting Navy acquisition chief on Jan. 20, after previous ASN RDA James Geurts began performing the duties of Navy secretary when the Biden administration came into office. The Senate confirmed Carlos Del Toro as secretary on Aug. 9, and Geurts retired from public service, leaving Stefany still in the acting position. There has been little news about the Biden administration selecting a new acquisition chief any time soon.

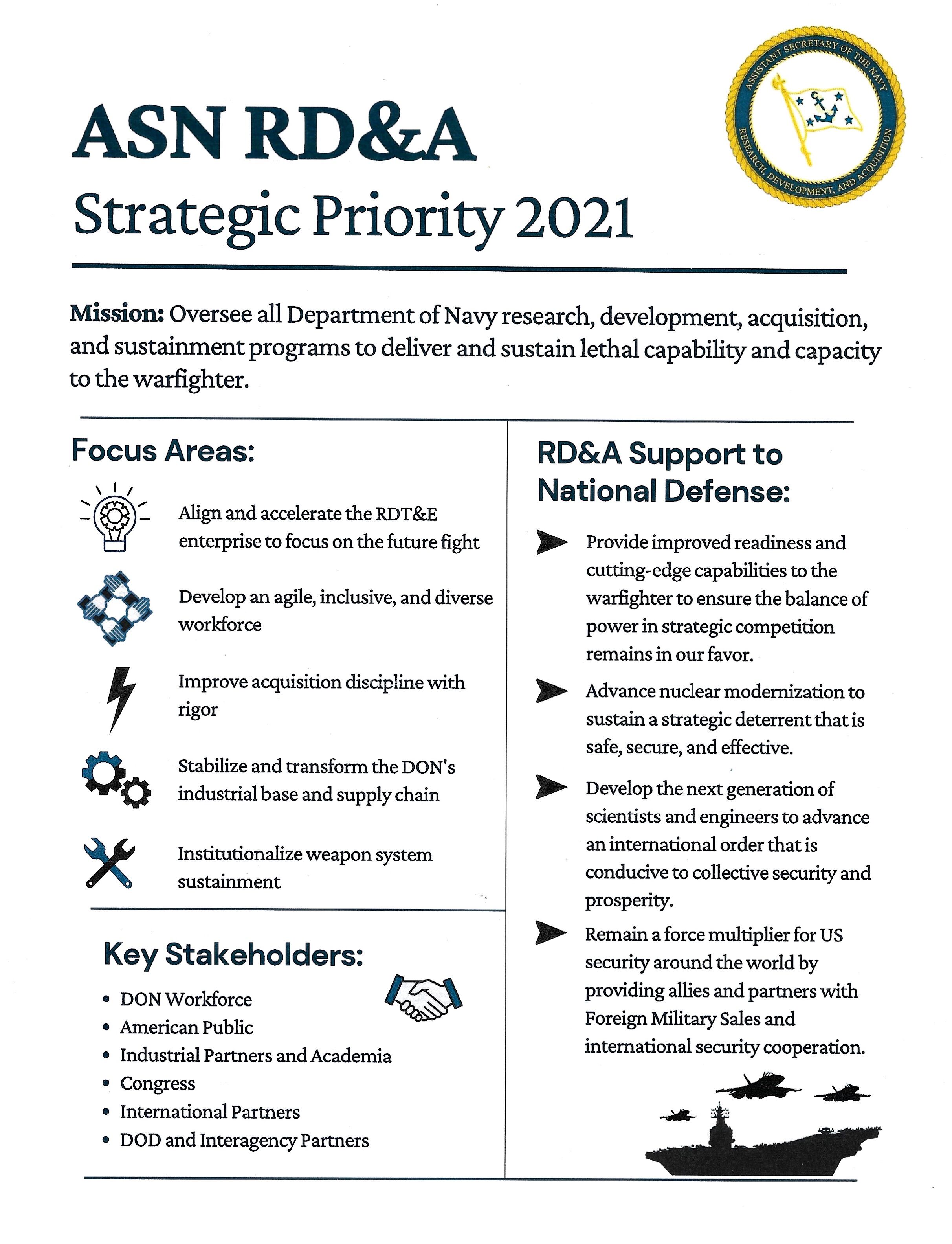

Stefany said that once it became clear he’d be in the acting position for a lengthier time, he put out a memo to the workforce on his FY21 priorities. He said nothing changed at the macro level — “it’s all about agility and innovation and providing war-fighting capability,” in line with what Geurts emphasized in his three-year tenure — but he wanted to highlight some focus areas and address a few challenges he saw in the pipeline.

First, Stefany wants to refocus the research, development, test and evaluation enterprise on future war-fighter needs. More specifically, he wants to align early science and technology work to the areas that the chief of naval operations and the commandant of the Marine Corps think will be critical in the 2030s and beyond.

The services already created an research and development board, which includes the vice chief of naval operations, the assistant commandant and the ASN RDA. The board will consider the CNO’s and commandant’s strategies and plans as well as identify focus areas for the science and technology community.

However, Stefany added, the board’s work hasn’t led to specific changes in the research community’s work. Last fall, Joan Johnson took over as deputy assistant secretary for RDT&E, and Stefany said she’s worked with the Office of Naval Research, the Naval Research Laboratory, warfare centers, labs, federally funded research and development centers, and more to realign their work to future war-fighting needs.

Stefany said the Navy previously spent a little bit of money on a lot of research areas; now, he wants to make larger investments in a few key areas that reflect the services’ stated priorities, while also retaining a smaller investment in other technology areas.

The second focus area for Stefany is to develop an agile, inclusive and diverse workforce, which he said was already a priority for the Navy and the Pentagon.

Third, he said, is improving acquisition discipline.

“Maybe it was because of COVID, maybe it was for other reasons, but I guess I was getting a sense that in some cases, we were finding things pop up that weren’t connected as well as we might have done before — like an acquisition strategy might not have had a good section on sustainment,” Stefany said. “Or in the build process, we were not catching some simple things.”

“So I just felt like we were running full speed, we were max teleworking, we were being agile and innovative and all that — well, we want to do all that, but we still need to provide high-quality ships and airplanes to our war fighters,” he said, describing this as a call to refresh training and focus on the basics of good engineering and program management.

Fourth is to stabilize and transform the industrial base.

Stefany said the Pentagon did a lot in the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic to help suppliers and keep money flowing to them despite challenges related to the coronavirus.

Additionally, Congress has set aside money to shore up the submarine industrial base, and lawmakers are beginning a similar but smaller effort for the surface ship industrial base. After a February White House executive order on security for American supply chains, the Pentagon has looked at cross-service enablers like batteries and microelectronics, but Stefany said the Navy needs to also identify uniquely naval products and suppliers that need additional investments.

And finally, Stefany said he wants to institutionalize weapons sustainment, “making it a common, normal part of our process.” He noted progress has been made, and that there are new tools — such as “Naval Supply System” and “Performance to Plan” — that help programs execute sustainment plans more effectively. But he stressed that each program needs to start with a solid sustainment plan.

“I think we need to start with: Have we thought through how we’re going to sustain this thing? Is the way we’re doing it the best way?” he said. “Who are all the stakeholders? Who’s in charge? Who is the accountable, responsible person? Getting some of that lined up, then start using the tools to make it better.”

Megan Eckstein is the naval warfare reporter at Defense News. She has covered military news since 2009, with a focus on U.S. Navy and Marine Corps operations, acquisition programs and budgets. She has reported from four geographic fleets and is happiest when she’s filing stories from a ship. Megan is a University of Maryland alumna.